NFPA 70B and the Resurgence of the Electrical Maintenance Program

Numerous articles have been written about NFPA 70B in recent months following the recommended practice becoming a standard. All this chatter and renewed interest is coming from the perception — and rightfully so — that failure to perform minimum electrical maintenance could lead to OSHA fines.

I’d like to believe that facilities that did not previously have an electrical maintenance program will now create one out of compliance. Furthermore, I hope this desire for compliance will lead to an observation that the facility has fewer failures and unplanned outages. Then, long-neglected facilities will reach the pinnacle of ongoing commitment to electrical preventive maintenance (EPM) and its benefits for reliability, safety, and lower cost of operation by preventing unplanned downtime.

The most basic EPM activity: the lowly thermographic survey

For a long time, I have used a phrase that’s more popular in the physical exercise community: Any activity is better than inactivity. When I have been asked over the years, “What should I be doing for maintenance?” my response has been consistent. If you only have $1 to spend, spend it on an infrared (IR) survey. It is a powerful tool with many benefits that can sometimes go unappreciated.

One of my earliest lessons in the importance of thermographic surveys occurred at a hotel. As a young technician and newly certified thermographer, my assignment was to perform an IR survey on equipment as directed by the client. Things went well as we scanned all the primary service entrance equipment and other portions of the power systems that the client felt were critical. Unfortunately, what was deemed critical didn’t include a motor control center (MCC) in the penthouse. Fast forward a few short weeks to when the hotel suffered a failure in that same MCC.

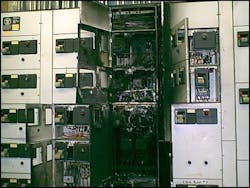

This failure not only destroyed the bucket (Photo 1), which had a loose connection, but it also created an arc fault that burned bus work inside the gear in half, thereby rendering the entire MCC unsalvageable.

At this point, the criticality of the gear became glaringly obvious. This MCC was the source of power for the hot-water heating system. Imagine the difficulty created when an entire hotel of guests had no hot water for their morning showers. It created a difficult conversation for myself and the facility engineer. We both learned a valuable lesson. Never leave a job site until every reasonable attempt has been made to scan everything inside the facility.

A second benefit of thermographic inspections is that other safety hazards and National Electrical Code (NEC) violations can be found even in equipment without a thermographic issue. For example, a fuse that is replaced with a short section of copper pipe or a set of jumpers installed (Photo 2) by a well-intentioned, but reckless, electrical contractor can create a major safety issue.

Yes, that picture was taken inside a facility; it was not staged. After immediately bringing this to our customer’s attention, we heard a story of how this particular breaker had been tripping repeatedly, causing unacceptable outages. The fix, which I’m sure was never openly discussed, was to install jumpers from line to load and effectively eliminate the breaker. This has been a powerful lesson as to the importance of always testing for the absence of voltage after opening a breaker and before beginning work.

Why is my main switch opening?

Facilities that seldom do maintenance could experience unexpected operations of protective devices after proper maintenance is completed. One such example was a bolted pressure switch at a plant we serviced. Many technicians have experienced a moment of dread when you push the trip button on a bolted pressure contact switch with all of your might and nothing happens — the switch doesn’t open. When this happens, you know you will probably not be going home early. But it happens, and we all know it’s a possibility anytime we work on a bolted pressure switch of any type.

The solution revolves around penetrating oil, some patience, and the occasional tug-o-war with a strap to pull the switch open. Please note that this work must always be performed on equipment in an electrically safe condition. With any luck after a good bit of cleaning and proper lubrication, the switch typically can be restored to operational status and closes properly. It is while following this type of repair that a new form of problem can occur.

After the maintenance and repair of the bolted pressure contact switch, our client called us in a panic. The switch had opened unexpectedly and could not be reclosed. They wanted us on site right away to close the switch and determine the reason it had opened.

As I drove up to the plant, I noticed that many buildings in the surrounding areas were also in the dark. As it turned out, the local electric utility had lost power, and the undervoltage relay associated with the switch had done its job and opened the switch. I explained to the client that the system had worked properly and that once utility power was restored, we would be able to close the switch. To roughly quote the property manager, “We have had numerous utility outages over the years and never needed to reclose the switch!”

Stuck switches are a great opportunity to discuss the importance of maintenance to avoid the normalization of deviation with your client. Once a switch is functioning mechanically, it is important to verify and demonstrate the ground fault and undervoltage/loss of phase relay operations for your customer.

There must be a reason for this low reading

Two jobs come to mind where a simple test resulted in finding a major issue that wasn’t directly associated with our scope of work. The scope of work involved testing WLI-style medium-voltage air switches. In the standard procedures I have used over the years, disconnecting the incoming feeder cable is not part of the work. My thoughts are that disconnecting the cable adds unnecessary time and additional risk to the job (human performance issues to get them bolted back up).

Instead, test the switch with the cables connected. If it meets the minimum value required by ANSI/NETA MTS–2023, Standard for Maintenance Testing Specifications for Electrical Power Equipment and Systems, move on. Note: This method requires communication and flagging of the opposite cable ends for safety.

Utilizing this method on these two jobs, we noted insulation resistance readings on one phase of the switch on the incoming cable side that were well below the recommended values in ANSI/NETA MTS. When this occurs, you must disconnect the cable to determine whether the issue is the switch or the cable/upstream equipment.

As you might imagine, the low reading followed the cable and connected upstream equipment; it was not a problem at the switch. At this point, valuing the client and wanting to ensure the issues are found, it made sense to present this information to the client and request permission to test additional equipment that was outside of the original scope of work. With approval from the client for the additional work, we disconnected the cable at the next termination point upstream. With the cable isolated, we tested the cable only to learn that it was not the cable was not the source of the problem.

In both cases, our troubleshooting attention turned to the main switchboard. We tested the gear to confirm it was on the gear side. It was. Initial inspection revealed no evidence for the low reading, so we began the work of taking things apart. All of this time and work to isolate the issue now paid off as boots were removed and stand offs were unbolted from bus work to reveal partial discharge and corona damage (Photo 3, Photo 4, and Photo 5). One simple test — and the tenacity to chase down a failing reading — headed off a potentially catastrophic failure.

While all test results might pass on this switch, a qualified technician would recognize this as evidence of partial discharge, which is often related to moisture building up in the switch and typically is directly related to the failure of the space heater in the gear. Left uncorrected, this seemingly minor issue can cascade into violent failure. Be vigilant during your routine inspections.

Conclusion

For more than 26 years, I have been an advocate for facilities of all types to perform maintenance of their electrical systems. Over those years, I have been amazed by the number of facilities that wouldn’t perform maintenance. The reasons are varied. “Our system is too small;” “We are lightly loaded;” or “Our production schedule or budget won’t allow for maintenance.”

In our own lives, we recognize the benefits of maintenance. Change the oil in your car. Fix that small water leak on the toilet water supply hose. It’s the adage of pay me now or pay me later. In my experience, it was rare to get a call about a failure from facilities that did some form of regular maintenance — acts of nature were the unavoidable exception.

As I reflect on all those years of maintenance activities, I wonder how many tens of millions of dollars we saved our clients by providing electrical preventive maintenance and preventing unplanned downtime. More important to me — and more difficult to quantify — is how much safer the working environment has been for those who interact with power system equipment. Engage your clients, and be the advocate for change and continuous improvement of their electrical maintenance program. Remember, more than 80% of a good electrical maintenance program is taking care of the daily simple things.

Electrical Testing Education articles are provided by the InterNational Electrical Testing Association (NETA), www.NETAworld.org. NETA was formed in 1972 to establish uniform testing procedures for electrical equipment and systems. Today the association accredits electrical testing companies; certifies electrical testing technicians; publishes the ANSI/NETA Standards for Acceptance Testing, Maintenance Testing, Commissioning, and the Certification of Electrical Test Technicians; and provides training through its annual conferences (PowerTest and EPIC — Electrical Power Innovations Conference) and its expansive library of educational resources.

About the Author

Mose Ramieh III

Mose Ramieh III is vice president, business development at CBS Field Services and has been in the electrical testing industry for 26 years. He is a Level IV NETA Technician with an eye for simplicity and utilizing the KISS principle in the execution of acceptance and maintenance testing. Over the years, he has held various positions including field service technician, operations, sales, business development, and company owner across four companies.