Using Electrical Analysis Tools to Map Out Non-Electrical Problems

Your busways, switchgear, and panel connections need to be the subject of thermographic analysis. But thermography has many uses beyond maintaining electrical infrastructure, even for those who are involved in electrical maintenance or electrical contracting.

If you’re part of an in-house maintenance department, you may be doing this work yourself. It’s typically the electrical group that buys the thermography equipment, and the uses of it tend to be limited to electrical maintenance. That’s a mistake.

If you’re part of an electrical services firm, you might do this work and think that’s pretty much it for using your thermographic equipment. That’s a mistake, too.

Let’s look at an example of where an electrical services firm can get electrical work from non-electrical energy problems. If you work in some other venue (e.g., in-house maintenance), you can apply the same logic for energy improvements in your facility. Maybe you can score some overtime to help pay down those holiday credit card bills.

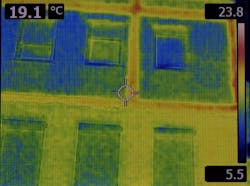

Conduct a thermographic analysis on the building itself--not just on the building envelope, but also on entities within the building. Look at anything that has power run to it.

The goal here is to determine where heat is generated, leaked, and pooling. To the best of your ability, also determine how it flows through (and out of) the building. Once you’ve put this together, you will be able to see where it makes sense to install fans to redistribute, redirect, or exhaust heat.

Let’s say this is one of those light industrial buildings you typically see off the interstate or find in industrial parks. The exterior walls of the factory part are corrugated metal and (maybe) insulated to R-4. These walls often have a gap here or there, further adding to the heat losses in winter.

The administrative offices part of the structure has a nice faux brick or stucco finish, is reasonably well insulated, and is on its own HVAC system. Generally, it’s not the front office that has the severe energy problems; it’s “the shed” behind the office.

During the summer, the factory workers prop open the doors and run many 120V floor fans. These are noisy, and extension cords are run everywhere to supply them. During the winter, space heaters and heat from the production equipment keep “the shed” reasonably warm.

You create a heat flow map, using data from thermograhic scans. You find that heat in “the shed” tends to either pool in certain areas or flow to the thermal weak spots of the building envelope.

In the winter, heat that should help make the place more comfortable is simply wasted. The summer floor fans don’t effectively solve the heat problem, for several reasons, including the fact that random placement causes them to fight each other. The building needs a means of managing the heat and air flow, so that winter waste heat no longer is wasted and summer waste heat is properly exhausted.

The real solution involves several steps:

- Fix the building envelope leaks.

- Add insulation panels or bats to bring the walls up to a reasonable level of thermal integrity.

- Install a forced air ducting system that collects heat from the points of generation and exhausts it in the summer and circulates it in the winter. This eliminates all those floor fans and extension cords and will use quite a bit less electricity. Of course, this will need a proper control system (electrical work) for those duct fans (electrical work), actuators (more electrical work), and sensors (even more electrical work).

It may turn out that moving equipment based on the heat flow documented by thermography also make sense. These equipment moves, too, require electrical work.

With the reduction in overhead, the plant will be more competitive and perhaps be able to take on new production. Installing new production equipment is going to mean more electrical work.

If your firm is an electrical services firm that performs thermography and you haven’t looked beyond electrical infrastructure, consider doing so.

About the Author

Mark Lamendola

Mark is an expert in maintenance management, having racked up an impressive track record during his time working in the field. He also has extensive knowledge of, and practical expertise with, the National Electrical Code (NEC). Through his consulting business, he provides articles and training materials on electrical topics, specializing in making difficult subjects easy to understand and focusing on the practical aspects of electrical work.

Prior to starting his own business, Mark served as the Technical Editor on EC&M for six years, worked three years in nuclear maintenance, six years as a contract project engineer/project manager, three years as a systems engineer, and three years in plant maintenance management.

Mark earned an AAS degree from Rock Valley College, a BSEET from Columbia Pacific University, and an MBA from Lake Erie College. He’s also completed several related certifications over the years and even was formerly licensed as a Master Electrician. He is a Senior Member of the IEEE and past Chairman of the Kansas City Chapters of both the IEEE and the IEEE Computer Society. Mark also served as the program director for, a board member of, and webmaster of, the Midwest Chapter of the 7x24 Exchange. He has also held memberships with the following organizations: NETA, NFPA, International Association of Webmasters, and Institute of Certified Professional Managers.