Like peeling away the layers of an onion, research into electrical injuries is revealing more all the time. It’s enough to bring a tear to the eye when the full extent of the potential damage to unfortunate victims — most from the workplace — is completely grasped.

In work spearheaded by the Chicago Electrical Trauma Research Institute (CETRI), a group that coalesced in 2009 to centralize more than two decades of scattered but intensive research into electrical injury and its treatment, researchers are finding that electrical shock can be as much a stealthy, progressive disrupter to the body as a silent immediate killer.

Chicago-area physicians, therapists, and scientists working under the CETRI umbrella are growing more convinced every day that electrical shock causes much more than devastating burns and other physical injuries (see Rare but Deadly). They’re finding it can trigger a chain of events that leads to potentially disabling changes in mood, personality, emotions, and cognitive functioning.

But the good news, as CETRI’s work and research is revealing, is that the prognosis for recovery is good and improving. Addressed early in the treatment process, these non-physical injuries can be mitigated to the point where the victim can function in daily life. The key is timely, aggressive, and focused therapy.

Armed with an expanding view into the full range of damage electric shock can produce, a core of about a dozen affiliated clinical investigators is helping

CETRI pioneer new treatment strategies. In addition to treating the injury’s physical toll, the CETRI regimen is incorporating an expanding focus on its less understood mind/body component. In the course of pursuing new avenues of treatment for the patients who come through a comprehensive treatment and rehabilitation program that feeds its research efforts, the institute’s work is becoming a model for other caregivers to purse a more comprehensive, multi-faceted approach to diagnosis and treatment.

“We’re banging the drum about electrical injury not being just a physical injury,” says CETRI’s Assistant Director Kristina Adams, Ph.D. “We’re out doing seminars at meetings of groups like the Construction Safety Council, trying to take any and every opportunity we get to help everyone better understand electrical injury and know what to look for.”

Beyond skin deep

By themselves, serious electrical burns and tissue damage are a challenging enough condition to address. But CETRI research is revealing that greater, but often less obvious, damage may be born by the body’s intricate neural structure. Its “wiring,” in essence, can be changed through disruptions the shock causes in the nervous system and musculoskeletal complex. With the brain and spinal cord deeply involved in pain, motor impairment and mental dysfunction loom as probable byproducts of electricity coursing through the body, producing a complex web of ailments and symptoms that can be hard to untangle.

Researchers have grown more interested in the phenomenon of alterations in mood, emotions, and cognition because they can be as dangerous as physical damage. Considering the impact on social interaction, job performance, sleep, quality of life, and a host of other routine day-to-day functions, these are potentially costly consequential “injuries.”

Numerous studies, many based on actual cases handled by CETRI, have found a strong correlation between electrical shock and the development of worsened mental states over time. Years of research have convinced Neil Pliskin, Ph.D., professor of psychiatry and neurology at the University of Illinois at Chicago, that electrical injury victims are at high risk of developing “emotion regulation” challenges.

A longstanding CETRI clinical investigator and the first neuropsychologist to join the formal study of electrical injury pathology in the early 1990s, Pliskin points to one recent study involving 185 electrical injury victims. It found that 75% of subjects developed at least one, and, in some cases, two or more, diagnosable mood-related changes post-injury, including depression. Notably, only 3% of that sample had prior contact with a psychiatrist or other mental health services provider.

“Rock-solid, emotionally stable individuals go through an electrical injury experience, and they’re different,” Pliskin insists. “They’re more anxious, don’t want to be around other people, some become very tearful or upset, or can’t tolerate stress. And the change — the level of disruption — is traumatic. These are people who haven’t been utilizers of psychiatric services now going through significant psychiatric changes.”

And the problems often don’t end there. Research has also found that some victims are prone to developing cognitive deficits. They seem to develop over a course of several years following the incident and likely spring from emotional changes. While generally not disabling, problems with memory and task completion are nevertheless disruptive.

“What happens, in studies where we compare these victims with others of their same age, they think more slowly and have a more difficult time paying attention,” says Pliskin. “Things that were once automatic are no longer automatic for some of these people. What they say is, ‘it’s not that I can’t do things, it’s just that I have to work so much harder to be able to do the things I could do before.’”

The mystery of how

For all the progress in discovering this predictable pattern in victims, researchers are still struggling to understand the mechanism. Numerous theories have been advanced, but the unique circumstances surrounding many electrical injuries complicate the effort to pinpoint cause and effect.

One of the most confounding mysteries is the onset of these problems without clear evidence of physical trauma that might be expected to lead to changes in behavior and thinking. While survivable electrical shocks can be violent, they only rarely involve head injuries of a severity likely to affect the brain; electrical current passing directly through the brain can cause traumatic brain injury. After years of studying electrical shock victims exhibiting psychiatric symptoms, Pliskin flatly rules out the idea that typical brain trauma is in play because the classical markers aren’t there.

“What we do know is that electrical injury isn’t traumatic brain injury (TBI),” he says. “Only a third of patients lose consciousness as a consequence of their injury. While there may be confusion and disorientation after the shock, it’s not a given they’ll lose consciousness. Others do develop head injuries where an explosion throws them back, and they hit their head. But others don’t.”

That’s left investigators searching for other possible causes. One theory is that it’s not physical; it’s that victims are wrestling with the unique emotional trauma of having been shocked. Memories of the incident, the suddenness and randomness of the event, along with the powerful realization that they could have died, might overwhelm victims. Left to linger without treatment, those symptoms can worsen and result in an experience approximating post-traumatic stress disorder.

“This can be very complex, an element of this that’s tied up in the circumstances of what happened and the nature of the injury,” says Pliskin.

A re-set theory

Then there’s the notion that something more inexplicable is at work. Some point to the still-common practice of using electro-convulsive shock therapy (ECT) to treat the hardest-to-treat depressive patients. While the exact mode of action in ECT was never reliably established, use of ECT does lead to mood changes, leading researchers to draw parallels. Essentially, the same thinking that led psychiatry to ECT at one time could provide at least some clue to what’s happening with shock survivors.

“I’m not equating the two, but the concept of being advertently exposed to an electrical field — and that having an impact on functional brain systems so that it changes someone’s ability to regulate their emotions — it’s just not that far-fetched,” says Pliskin.

Another theory invokes the mind/body connection concept. It holds that the electrical shock itself, independent of any serious tissue burn, fundamentally damages the body’s muscle and peripheral nerve complex — and that the trauma gets coded into the central nervous system. The resulting pain, sensory changes, and effect on motor functions lead to physical changes in the brain’s circuitry that can produce changes in mood, behavior, and cognition.

The idea has a basis in the study of pain treatment and therapy, says Raphael Lee, M.D., professor of surgery and medicine at the University of Chicago, whose pioneering work in electrical injuries set the stage for the eventual establishment of CETRI.

Pain management specialists, he says, are convinced that peripheral nerve injury can lead to changes in the brain. That leads to changes not only in the experience of pain, but also emotional and cognitive expression. The fact that so many electrical shock victims exhibit these problems — even in cases where serious burns aren’t involved — leads researchers to conclude that the shock itself can actually damage nerves.

“Someone gets a brief electrical shock, there can be substantial damage to peripheral nerves and muscle that is not caused by generalized heating, where severe tissue injury would be expected to cause nerve damage,” says Lee. “Exactly how it happens that electrical forces themselves could, in a brief moment, cause significant injury to muscles and nerves, is not clear. That was a controversial idea at one time, but today that controversy is gone.”

Adding insult to injury

While the shock event may last only milliseconds, its effects can not only persist, but also worsen over time. An ensuing cascade of pain not to mention emotional and cognitive disruptions can take root.

In the course of following victims over an extended period of time, CETRI researchers have seen a pattern of regression — from fewer and milder symptoms right after the event to more acute symptoms months later.

The explanation, Lee says, lies partly in what pain researchers have learned about how the brain reacts to nerve trauma and processes pain signals. Rather than the body becoming more inured to the resulting pain, it can actually become more hyper-aware of it, resulting in a heightened sensitivity to pain. The same mechanism may be at work with mental functioning.

“That delay is a progressive change due to maladaptive behavior, where a person gets an injury and the complex neurophysiology isn’t working the way it used to because of the injury,” says Lee. “Over time, it affects the centers in the brain responsible for emotion and memory, and it doesn’t improve them — it makes it worse.”

Understanding how and why electrical shock produces such an array of changes is important. But what may matter more is the ability to recognize symptoms and find an effective way to treat victims. In that regard, CETRI is leading the way.

Spotting trouble signs

While treatment and rehabilitation encompasses a mix of approaches, the emphasis is increasingly on the importance of early intervention, followed by focused and aggressive treatment targeting symptoms that can produce long-term emotional and physical disability (see Aftermath of an Electrical Accident). Unfortunately, that’s complicated by uncertainty.

In a clinical setting, says Pliskin, it’s hard to reliably identify who will develop psychosocial difficulties. And it’s still not known what factors and variables make them more likely to take root. But, he says, a simple awareness of the potential and an understanding of the “havoc” they can produce in a victim’s life means “the earlier that you can sensitize people and recognize those who might be in trouble, the better.”

Thus, heading the list of best practices advised by CETRI is thoroughly evaluating patients on intake and being able to quickly bring mental health professionals into the picture. It is a strategy CETRI is uniquely able to employ, given its access to a full range of experts — and one it says should be adopted by other caregivers to the extent possible.

“It’s important to know the nature of the beast when a person starts out on a treatment plan after an electrical injury,” says CETRI’s Adams. “With early detection of problems and a prognosis from a cognitive standpoint, people are in a position to get better, more focused treatment.”

A treatment regimen along the lines of that used to help victims regain physical capabilities that the shock impaired can be effective. By incorporating therapies that encourage victims to confront feelings and emotions and help them maintain or improve memory and cognition, treatment professionals will be directly targeting symptoms that are likely to fester and worsen if left untreated.

Forestalling decline

That can be critically important, given the high stakes for the victim, their families, and their gainful employment. The average age of a patient who goes through the CETRI program is 35, Adams says, which means many more working years where they’ll need their full physical and mental faculties to thrive.

Plus, victims not fully treated likely won’t be as productive. And employers, many still largely unaware of the full nature and complexity of electrical injuries, may lack the skills and patience to deal with chronically afflicted workers. In addition, treatment delays or detours due to inaccurate or incomplete diagnoses will also add costs and extend the recovery period.

Given what researchers now know, Lee concludes, electrical injury generally warrants aggressive, thoughtful, and

comprehensive treatment. That marks a departure from the long-held belief that victims of shock and other physical trauma that don’t show visible injuries can simply get up, dust themselves off, and get back to work.

“Electric injury in the workplace is a common cause of long-term disability, and one of the most common outcomes of individuals who have a disabling problem is that they become disabled in a permanent sense,” he says. “So I’m convinced that early intervention, early aggressive monitoring, and rehabilitation approaches are helpful.”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR 1: Rare but Deadly

Workplace electrical injuries are getting rarer thanks to improved safety practices, rules, and equipment. That’s something to celebrate when the toll of those injuries is tallied.

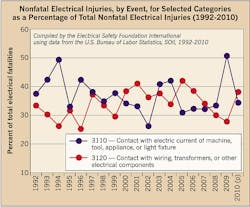

Compiling U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data, the Electrical Safety Foundation International, Arlington, Va. — a 501(c)(3) organization dedicated exclusively to promoting electrical safety in the home, school, and workplace, says fatal electrical injuries were cut in half between 1992 and 2010, with the pace accelerating since 2006. Fatalities fell by one-third from 2006 to 2010 alone.

Meanwhile, non-fatal injuries fell 60% in that 18-year span (Figure). Injuries were highest in the construction and electric utility industries, where injury rates were 0.6 and 0.2 per 10,000 workers between 2003 and 2010. Contact with current from machines, tools, appliances, etc., and contact with transformers, wiring, and similar components caused the most injuries.

But what electrical injuries lack in incidence they make up for in consequence. The Chicago Electrical Trauma Research Institute (CETRI) has compiled data that measure the toll these injuries may be exacting.

Citing figures from the Electric Power Research Institute, Palo Alto, Calif. — an independent, non-profit organization that conducts research, development and demonstrations for the electric utility industry — CETRI says electrical injuries’ cost to employers has been estimated at $15.75 million per case in direct and indirect costs. It also cites data that puts the average cost of just treating burns from electrical injury at about $14,000.

Another statistic cited by CETRI shows one-quarter to two-thirds of injuries caused by contact with overhead power lines resulted in more than 31 days away from work. The range for other occupational injuries and illnesses was between 18% and 20%.

The bigger costs, though, likely stem from treating the non-physical component of the injuries — the emotional and cognitive issues that often accompany the injuries.

That quest often involves heading down blind alleys and arranging consultations with multiple specialists. CETRI cites one study in which 31 patients participated in 83 separate consultations, but 80% of those visits yielded no clinical diagnosis.

Statistics show non-physical problems are prevalent. CETRI says half of all victims experience anxiety, and 25% endure chronic pain. In many victims, weight gain, fatigue, depression, poor concentration, and post-traumatic stress disorder show up one to six months after the event, and physical symptoms like numbness, tingling, and weakness, can appear within two months.

SIDEBAR 2: Aftermath of an Electrical Accident

Electrical injuries — the most common form of work-related burn injuries and a major cause of work-related deaths — result in approximately 1,850 emergency department visits every year in Ontario, according to the Electrical Safety Authority. The staff at St. John’s Rehab, part of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto, is helping patients combat the adverse and often invisible effects of such injuries. Canada’s only dedicated electrical injury rehabilitation program, St. John’s has been providing customized, comprehensive assessment and care to people suffering the long-term effects of electrical trauma since 2003.

According to the experts at St. John’s, not all electrical injuries are created equal — each patient presents different symptoms at different times. They may experience neurological symptoms such as numbness, weakness, memory problems, paresthesia (paralysis of the tongue), fatigue, and chronic pain, as well as psychological symptoms, such as anxiety, nightmares, insomnia, and flashbacks of the event. Because these symptoms often arise unpredictably, electrical injury survivors are often challenged or misunderstood by family, co-workers, insurers, and employers. Ted (an assumed name) is one such survivor.

After 600V of electricity radiated throughout his body, Ted showed no visible signs of trauma. He even continued to work for months following the accident — until the after-effects began to reveal themselves below the surface. Today, Ted’s recovery is ongoing. He works with a multi-disciplinary team of nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, neuropsychologists, and other health professionals at St. John’s Rehab to address needs specific to his condition. He suffers from severe post-traumatic stress disorder, with lack of sleep being one of the most problematic post-accident conditions. With the help of his customized rehabilitation program, his attention, concentration, and memory have improved. His anxiety and depression have also decreased, and he is finally able to get some sleep.

“I was completely dysfunctional,” says Ted. “I started having nightmares every night. I couldn’t sleep. My muscles were weak, and I kept losing my balance. I still hear ringing in my ears. St. John’s Rehab gave me my life back.”

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].