When you inspect 300-plus residential solar installations each month, they all start to look alike — sometimes in a frightening way. For Tommy Davis, the scary part was the box housing the system disconnect switch.

“If there’s no space in the panel for a two-pole breaker opposite the main breaker, or the photovoltaic (PV) system is larger than the capacity of the panel, the solar companies are feeder tapping the line-side wires before the main breaker,” says Davis, whose four-decade career includes serving as a master electrician and instructor.

The two-pole breaker or fused disconnect must be mounted within 10 feet of the tap. If there’s not enough room on either side of the panel, then it winds up being mounted below.

“Now you have a switch at toddler height,” says Davis, who began inspecting PV installations in Prince George’s County, Md., in the spring of 2016. “Any knife blade switch 60A or less has no guard shields over the line-side terminal. Those terminals are powered off the utility — no overcurrent protection. All a child has to do is flip that little latch, and they’re into some deadly stuff.”

That latch should be secured with a lock, nut and bolt, or a zip tie. But in Davis’ experience, it often is not.

“Maybe the utility company secures the outside [box], but no one is securing the ones on the inside,” he says. “I encouraged my colleagues to carry UV-protected zip ties, and, after the inspection, put it through the locking mechanism.”

UL and NEC Tighten Requirements

Enclosed and dead-front switches have been used in various commercial, industrial, and residential systems for a long time, as their UL standard number indicates: 98.

“That’s a pretty low number in terms of standards,” says Ken Boyce, UL principal design engineer. “It probably goes back to the early 1900s. So this is a very, very mature technology in terms of these types of switches.”

About 10 years ago, UL developed 98B because the disconnect switches were being used for residential solar installations.

“The main difference is that many of the traditional applications for these types of switches, even when the switch was open, you’d still have power on the line-side terminals, but the switch would disconnect power from the load-side terminals,” Boyce says. “In PV applications, that may not be the case. So, you could have terminals on both sides energized at the same time because the arrays are allowed to be interconnected with the grid.”

Both UL 98 and UL 98B require a locking feature. That’s consistent with the changes adopted in the 2020 NEC, which requires readily accessible PV system disconnect enclosures to be either locked shut or openable only with a tool.

“Some of those output circuits are DC, and, depending on how they are connected, there could be back-fed circuit breakers or switches,” says Michael Johnston, NECA executive director for standards and safety. “That means even when the switch is in the OFF position, there could be energized parts on the line and load side.”

How Many Injuries and Deaths?

The number of U.S. solar installations passed 2 million in May 2019, according to Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables and the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA). As Davis’ experiences show, that means a lot of enclosed switch boxes are sitting around unlocked, although no one tracks how many. But there’s also scant evidence (even anecdotally) that they’ve caused injuries or death.

“I haven’t heard of it being much of an issue in residential settings with people opening those devices and injuring themselves,” says Bob Solger, founder and managing partner of Solar Design Studio, a Platte City, Mo., firm serving the Midwest and West Coast. Even so, UL is keeping an eye out.

“Sometimes, problems can emerge — things that we didn’t expect,” Boyce says. “We always want to make sure we’re learning the lessons of the field history — what is it telling us? — and trying to implement those as effectively as possible. Sometimes, that results in code changes or standards changes. Sometimes, it results in educational campaigns.”

Davis believes in erring on the side of caution. “I hope to hell there are no statistics,” he says. “That means no child has been injured yet. Many [people] have asked for hazardous statistics. I have none but have been able to accomplish what I have because it is just plain old common sense.”

In a live stream video on April 21, 2020, (“Mike Holt Live Q&A!”), NEC Expert Mike Holt lauded Davis’ crusade. In 2019, Davis successfully lobbied the Maryland legislature for a law requiring a lockout tag with a metal or plastic strap be used to seal closed a knife-blade disconnect switch box on residential solar installations. Now retired, his latest effort is proposing that UL 98 be revised to conform with NEC 2020.

“My submission is to scrap the hinged door requirement and require a screw-on cover just like most pieces of electrical equipment,” Davis says. “If I got 188 members of the Maryland General Assembly, both Republican and Democrat, to vote for my bill, and now I’ve got Mike Holt calling me his hero for what I’ve done, I guarantee that my submission will be approved.”

Looking Ahead Rather Than Back

These new 2020 NEC requirements aren’t retroactive, however. Also, with the exception of Maryland, the installed base of unsecured boxes will still increase in the short term simply because municipalities and other jurisdictions typically take time to adopt the latest Code requirements. It’s also important to remember the Code is a baseline. Jurisdictions are always free to exceed it.

Is there a chance that some jurisdictions could require installers to go back and secure boxes that were previously installed? This is an unlikely scenario and one that’s unwelcome by some.

“I do not think that existing installations should be retrofitted to comply with newly enacted codes or standards,” says Russ LeBlanc, NEC expert, inspector, and safety consultant. “Doing so could start a precedent that may be difficult to come back from.”

Some states already have rules preventing retroactive changes.

“Rule No. 3 of the Massachusetts Electrical Code addresses existing installations,” LeBlanc says. “It states: ‘Additions or modifications to an existing installation shall be made in accordance with this Code without bringing the remaining part of the installation into compliance with the requirements of this Code. The installation shall not create a violation of this Code, nor shall it increase the magnitude of an existing violation.’”

“There’s no way you can go back and retrofit hundreds of thousands of installations, especially when it’s been demonstrated that there’s no documented problem in the field,” says Jim Rogers, owner/operator of Bay State Inspectional Agency in Vineyard Haven, Mass., and chair of NEC Code-Making Panel 4. “It’s fine if you want to get ahead of the curve so there never are any problems.”

There is Also a Philosophical Aspect.

“While I think securing equipment doors or covers is an important step, there are many other types of electrical equipment that can still pose a shock hazard: light sockets, table lamps and floor lamps, receptacles, time clocks, and fuse holders, to name a few,” LeBlanc says. “Should these be retrofitted, too? I think not. GFCI and AFCI devices provide better protection than standard overcurrent devices,” he says. “Should we retroactively replace all non-GFCI and AFCI breakers, too? Where would we draw the line? There are existing rules in the NEC to address equipment replacements. That’s how it should be handled.”

Solar systems also aren’t the only residential installations using these types of boxes. For example, countless residential AC units have lockable boxes that are unsecured. That also raises a question: Should a future NEC extend 2020’s solar requirements to non-PV installations that use the same enclosures?

“Chapter 1 of the NEC would be the place to do it,” says Johnston, adding that this is his personal opinion rather than the official position of the NFPA, the NEC Correlating Committee, or the NFPA Standards Council.

“But even more effectively, the product standards for those types of equipment could be modified so that if something is going through the testing and evaluative process at the testing and certifying laboratory, and they didn’t meet the defeat or the locking mechanism in the off position, they wouldn’t get a certification or a listing mark.

“Sometimes, it’s the chicken-and-egg thing with the Code. Sometimes the product standards will drive the rules in the NEC, and sometimes the NEC drives the rules in the product standards. I feel that this may be the case to try to expand this to other similar types of equipment globally.”

Going Beyond the Code

Like authorities having jurisdiction, electrical contractors have the freedom to go beyond the Code, whether it’s for PV, A/C, or any other system using these enclosures. For example, they could advise homeowners that although the local code currently doesn’t require the box to be secured, doing so is an inexpensive ounce of prevention. This recommendation also could surprise homeowners unaware of the risk, and thus reflect positively on the electrical contractor for bringing it to their attention.

“A good installer should communicate effectively with the customers about this hazard,” LeBlanc says. “It’s a relatively easy fix during the initial installation of the equipment, too. Just secure the door with a nut and bolt. Done.”

Rogers agrees: “You can always do that as a positive for your client. There’s nothing that says you can’t do more than Code.”

Other trades could do the same, as could home inspectors and general contractors.

“I want everyone to start looking at these boxes through the eyes of a child, and put a screw and a nut or a zip tie through the locking mechanism,” Davis says.

Finally, besides contractor proactivity and the NEC, state-level changes also can minimize the risk by eliminating safety disconnects.

“Years ago, when the solar industry began to evolve, that was to prevent the inadvertent possibility of an inverter backfeeding a circuit,” Solger says. “However, grid-tied inverters are in effect all UL-listed, and they have a 5-minute delay before they connect up to the grid. Grid-tied inverters do not produce voltage. They only inject current into the grid.

“In California, in residential installs, system sizes 10kW and below, they’re waiving the disconnect requirement because it’s not needed. I’d like to see it go away because it’s a cost item on a project that’s unnecessary.”

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer. He can be reached at [email protected].

Sidebar: Record-Breaking Residential Installs

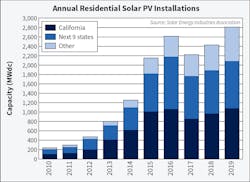

Thanks to public policies such as tax incentives and the declining cost of PV equipment, 2019 set a record for residential solar installations, with a 15% increase over 2018. That’s according to the “Solar Market Insight Report 2019 Year in Review,” published by the Solar Energy Industry Association and Wood Mackenzie Power & Renewables.

“From 2020-2021, residential growth will range from 9% to 17% due to both emerging markets with strong resource fundamentals like Florida and Texas and markets where recent policy developments have increased our near-term forecasts,” the report says.

Sidebar: Relevant NEC 2020 Rules

690.13 Photovoltaic System Disconnecting Means. Means shall be provided to disconnect the PV system from all wiring systems including power systems, energy storage systems, and utilization equipment and its associated premises wiring.

(A) Location. The PV system disconnecting means shall be installed at a readily accessible location. Where disconnecting means of systems above 30V are readily accessible to unqualified persons, any enclosure door or hinged cover that exposes live parts when open shall be locked or require a tool to open.

Informational Note: PV systems installed in accordance with 690.12 address the concerns related to energized conductors entering a building.

690.15 Disconnecting Means for Isolating Photovoltaic Equipment. Disconnecting means of the type required in 690.15(D) shall be provided to disconnect AC PV modules, fuses, DC-to-DC converters, inverters, and charge controllers from all conductors that are not solidly grounded.

(A) Location. Isolating devices or equipment disconnecting means shall be installed in circuits connected to equipment at a location within the equipment, or within sight and within 10 ft of the equipment. An equipment disconnecting means shall be permitted to be remote from the equipment where the equipment disconnecting means can be remotely operated from within 10 ft of the equipment. Where disconnecting means of equipment operating above 30V are readily accessible to unqualified persons, any enclosure door or hinged cover that exposes live parts when open shall be locked or require a tool to open.

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].