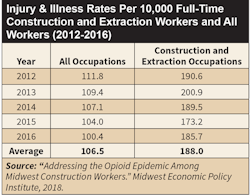

The world that electrical workers and others in construction inhabit presents a maze of threats to physical well-being. Exposure to slips and falls, electric shock and burns, strikes by objects, repetitive use injuries, sprains and chronic joint aches and pains comes with the territory on job sites. (Fig. 1).

Now an ominous new threat looms — one closely linked to traditional occupational hazards workers routinely face and try to manage. In a word: opioids, one that’s wormed its way into the American cultural lexicon in recent years. In more than a word: a complex of addiction, dependence, failing health, diminished faculties, potential job and career loss, family breakdown, and (for the unluckiest) a fast-downward spiral that can easily lead to overdose and premature death. Not the sort of routine hazards generations of skilled-trades workers have learned to live with, but a stew of toxic new ones that may have these workers squarely in the crosshairs.

As opioid abuse and addiction spreads, nationwide attention to the crisis is expanding to include how usage of these prescribed opium-based and synthetic painkillers and their illicit cousins may be linked to workplaces. Everyone is exposed because most users of opioids — legal and illicit — hold down jobs. But there’s growing evidence that those in construction occupations are among the most likely to use opioids, and, in turn, run the risk of becoming dependent or addicted. The reason: The physically demanding nature of the work, a “get-’er-done” culture, workforce demographics, and the structure of employment create an environment friendly to prescribed painkillers, prolonged usage, and comparatively easy access to drugs in social and work circles.

“We’re in a tough industry where people don’t complain. You find ways to work through pain, and you don’t get paid unless you work,” says Jeff Scarpello, executive director of National Electrical Contractors Association’s (NECA’s) Penn-Del-Jersey chapter, explaining why construction workers may be easily enticed by painkillers to cope with injuries and ailments caused or exacerbated by their work.

And there’s evidence that many construction workers are obtaining them, usually through readily compliant physicians. If that’s not possible, however, they’re increasingly turning to the street. That’s where people can find both prescription pain pills and cheaper, more potent and possibly lethal substitutes like fentanyl and even heroin when prescriptions run out after they’ve become hooked or increasingly dependent.

In Ohio, for instance, the state Bureau of Worker’s Compensation has found evidence that injured construction workers have a long history of filling more prescriptions for narcotic painkillers than those in other workplace sectors. In 2016, per the agency, 73% of injured construction workers were prescribed a narcotic painkiller, and the number totaled 13% of prescriptions written for all on-the-job-injuries statewide.

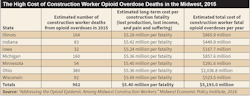

Research recently conducted by the Midwest Economic Policy Institute produced an estimate that almost 1,000 workers employed in the construction field in seven Midwestern states died from an opioid overdose in 2015 (Fig. 2). An executive summary of the research released in February also stated that opioids account for about 20% of all prescription drug spending in the construction industry, 5% to 10% higher than in other industries. It also noted that the injury rate for construction workers is 77% higher than the national average for other occupations, and that about 15% of construction workers have a substance abuse disorder, compared to the national average of 8.6%. Furthermore, in those Midwestern states, opioid prescriptions were an element of between 60% to 80% of workers’ compensation claims in recent years.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) unveiled research findings in August showing construction workers are especially vulnerable. Analyzing the occupational intersection with overdose deaths, agency researchers found that 7,400 people linked to employment in construction in 21 states died from drug overdose deaths between 2007 and 2012. Crunching the data, CDC concluded that, compared to others, construction occupations “had the highest proportional mortality ratios for drug overdose deaths and for both heroin-related and prescription opioid-related overdose deaths.”

Opioid Awakening

Growing publicity of what’s fast becoming a nationwide epidemic of opioid overdose and now strong evidence of high correlation between construction-related work and opioid usage are sending waves of alarm through construction trades, electrical contractors and workers included. Now better aware of their exposure, more people in the electrical construction world are starting to face the opioid abuse problem head on, either confronting actual cases in their ranks or trying to head off their occurrence.

Contractors in Scarpello’s NECA chapter are on the front lines. Working in a region of the country where the opioid epidemic is comparatively raging, they’ve been jolted by the opioid overdose deaths of workers their ranks employ — “nine or 10 members” of IBEW Local 98 in Philadelphia in the last year, Scarpello says. On top of that, two contractors have recently lost adult children to overdose.

“It’s hitting close to home,” Scarpello says. “It’s almost becoming the number one issue that we’re now trying to tackle as an organization.”

Charles MacDonald, president of Charles H. MacDonald Electrical, Inc., Philadelphia, has witnessed the opioid problem on multiple fronts. A daughter became addicted to prescription opioids and has been free of their grip for two years, he says. Evident opioid abuse and addiction by one of his own union workers came to a head on a job site, when coworkers and managers staged an intervention that led to the worker being replaced by an apprentice and ultimately entered a union-sponsored drug rehabilitation program.

“There have been some cases where we’ve had men addicted and unable to do the work correctly, and we’ve had to let them go,” he says. “But the first concern is safety, for the person affected and those around him and the customer. We’re working off the ground on lifts and with electricity; we’re not cutting grass out there.”

In upstate New York, electrical contractors in the Rochester chapter of NECA have become more aware of the opioid problem, says Peter Stoller, executive director. So far, he says, contractors have not reported any notable incidents linked to usage, but they well understand that the nature of their work leaves employees exposed.

“Our guys are at greater risk. And when they’re injured, doctors often prescribe these opioids for pain management,” he says. “That’s where the problem can begin to snowball, when the prescription runs out, and they can move from dependency to addiction.”

Although there have been no documented problems with his workforce, Vic Salerno, CEO of O’Connell Electric, Inc., Victor, N.Y., says his eyes have been opened to the potential for danger. He’s seen the over-prescription component of the problem firsthand, challenging a pharmacist for giving him what he thought was an overly generous amount of oxycodone to control pain following an injury, and learning of an overdose incident involving another contractor’s worker on an O’Connell job site.

“A mechanical contractor worker apparently shot up with Oxycontin on the job and overdosed; security personnel showed up, administered Narcan (an overdose drug) and saved his life,” he says.

Gauging the Risks

That’s a rare, worse-case scenario, but others just as troublesome face contractors worried about the opioid abuse epidemic showing up on their doorstep.

One is a workforce increasingly riddled with workers in various stages of reliance on opioids. Those who get ensnared in their addictive web — and that’s not everyone — can become increasingly consumed with avoiding withdrawal, the primary agent of addiction. That can mean a fixation on keeping prescriptions filled or finding alternatives when they either run out or become too expensive.

The result can be workers who aren’t fully engaged because they’re struggling with withdrawal or the side effects of drugs that mask pain by dulling the senses. That can put workers in potential danger and quality work in jeopardy.

“You have to be able to communicate and have your thought processes going,” says Ken MacDougall, director of business development for the NECA Penn-Del-Jersey chapter. “This can be a dangerous business. You do a lot of things over and over and complacency can sometimes set in. And then you bring opioids into the picture?”

Then there’s the problem of worker availability and readiness. Workers struggling with dependency may be less reliable, and contractors can pay a price.

“When someone is in the grips of this and they’re not showing up for work, one downside for a contractor is manpower scheduling,” says MacDougall. “It can definitely affect contractors in the way they’re set up to deliver projects.”

Another related concern for contractors is the impact on the bottom line (Fig. 3). Worker injuries ratchet up premiums for workmen’s compensation insurance and adding in treatment for workers who get hooked on opioids can add another dimension to the problem.

Painkillers, used responsibly, have long helped injured workers stay on the job, to the benefit of contractors. But growing misuse and abuse of stronger, potentially more addictive opioids may be eroding their overall value.

The Value of Intervention

Yet there’s some evidence that funding treatment is a worthwhile investment. The Midwest Economic Policy Institute research says a construction worker with an untreated substance abuse problem costs an employer about $7,000 a year in excess health care expenses, absenteeism, and turnover. But it said keeping a worker on the payroll while he or she is in a recovery program may, by comparison, pencil out to the tune of $2,400 in annual savings.

Aggressive addiction intervention and treatment, along with efforts to encourage more responsible and careful use of painkillers, are emerging as key strategies for dealing with workers at risk in the construction industry. They’re fast replacing a punitive, zero-tolerance mindset as understanding of the scope and nature of the addiction problem grows.

IBEW Local 98, MacDougall says, has instituted new rules for its workers health plan, limiting the amount of opioid painkillers doctors can prescribe for members. Whereas a 30-day supply was often a given, it’s now been reduced, in some cases, to as little as three or four days. The restrictions, he says, reflect growing understanding of their addictive power and the fact that physicians are often too quick to prescribe painkillers.

Encouraging and even trying to mandate limited exposure to prescription opioids, Scarpello says, is a key first step to getting a handle on the problem.

“It’s highly unlikely that people are going to stop using painkillers, but we have to start focusing on responsible usage and non-opioid alternatives for dealing with pain,” he says.

There’s also an important educational component. While public awareness of addiction and overdose risk has grown, a clear understanding of how easily casual usage can lead to problem may be lacking. Employers and worker representatives in the construction industry are working to reverse that.

“Workers need to be told that they should think long and hard if they’re prescribed an opioid for pain management,” says Stoller. “It probably should be a last resort.”

At O’Connell Electric, information about the dangers are now woven into worker safety programs and events. At a recent company safety picnic, Salerno says a county medical officer spoke to a gathering of 900 employees and customers about the national opioid crisis.

“It’s become obvious to me that this is a major problem, but what’s aggravating is that a lot of people still don’t have a clue about what’s going on,” he says.

Managing the Problem

Until more people do, and risks are better understood and sidestepped, developing strategies for addiction, treatment, and recovery may emerge as the best approach. That may be the case in the construction arena, where a business boom is putting a premium on obtaining and retaining workers, and there’s acknowledgement that part of the workforce, now skewing older and less limber, will continue to be drawn to prescribed or even illicit pain management drugs.

That’s created an opening for the Allied Trades Assistance Program, formed by Philadelphia-area trade unions, including IBEW locals, to assist members struggling with substance abuse and mental health issues. The opioid problem has put ATAP into higher gear, spurring it to educate members on the risks, get at-risk or addicted workers into credible evaluation and treatment programs, and help manage their rehabilitation.

Ken Serviss, ATAP executive director, says one of the most valuable services it provides is training select union workers to be “peer advocates” capable of spotting warning signs of substance abuse and being a job-site mentor of sorts to those who are recovering from addiction or abuse.

“They’re not counselors, as such, but they’re there to help determine if problems are going on,” he says. “An extremely important role is the ability to recognize signs of relapse.”

Opioids clearly present a knotty problem for construction workers and their employers. But as programs like ATAP demonstrate, there may be paths out of the thicket of opioid over-availability, misuse, abuse, and even full-blown addiction. The key is recognizing the problem, meeting it head on, and, most importantly, adopting an approach of smart management when workers are caught in opioids’ clutches.

“There’s greater awareness now,” MacDougall says. “There are few in our industry who don’t know there’s an epidemic that’s reaching into our industry and threatening to take our people and ruin lives and families.”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR: More Focus on Workplace Injuries Might Help Stem Opioid Crisis

“Prevention is the best cure” may be a hackneyed saying, but it could be an operative one for construction contractors worried about feeling the effects of the opioid crisis.

Reducing on-the-job injuries that can draw workers to prescription opioids for pain relief could be a way to attack the abuse and addiction problem at its roots. Work-related injuries aren’t the only kickstarter for painkiller use, but their frequency in construction work, combined with the industry’s high rate of opioid usage, may point to a strong link worth trying to weaken.

Ken MacDougall, director of business development for the National Electrical Contractors Association (NECA) Penn-Del-Jersey chapter, says reducing workers’ vulnerability to injuries could translate to less need to get started with opioid painkillers.

“Something as simple as stretch breaks, giving workers gym memberships, and things of that nature could help reduce the incidence of injury,” he says. “And improved job-site analysis where crews get together and go over the day’s tasks can get everyone in the mindset of staying alert to hazards.”Jeff Scarpello, the chapter’s executive director, says he sees evidence that contractor safety coordinators are getting more aggressive on preventing even common injuries. The big worries are catastrophic electrical injuries, but preventing slips and falls, the top job-site injury source, is on the radar, as is proper technique for lifting and carrying items.

Over time, technology could also play a bigger role in preventing injuries. More construction contractors are experimenting with wearable technology to better monitor workers on job sites. Sensors embedded in work clothing or clip-on gear could help detect workers engaging in unsafe work practices or getting too close to job-site dangers. That could emerge as an important element of more proactive efforts to keep workers safe and away from mishaps that can put them on the road to opioid abuse.

Another element of prevention might entail limiting the progression of injuries. A Midwest Economic Policy Institute study on opioids in the construction workplace suggests more liberal injury leave policies could allow workers to recover more fully. Returning too early, it says, heightens the risk of re-injury and the possible need for painkillers. The study’s list of recommendations for combating the crisis also includes the caution that opioids may be less effective than anti-inflammatory medicines and physical therapy for treating common job-site injuries to the lower back, knee, and shoulder.

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].