As the push for building de-carbonization gains steam, it’s looking as if electrical professionals might have a key role in addressing one of initiative’s stickiest but most central challenges: bringing existing structures, over time, into the all-electric fold.

Many structures now reliant on natural gas or other fossil fuel-derived energy for heating and cooling likely lack the electrical infrastructure needed to handle higher and more complex electrical loads that will come with full electrification. Transitioning not only to heat pumps and other electrical appliances, but also in line to have more high-efficiency equipment and added building load through increased incorporation of electric vehicle battery charging, for instance, much of the existing building stock in parts of the country where de-carbonization is being pursued might ultimately require substantial electrical upgrading and retooling.

Recent studies on de-carbonization strategies highlight the problem of buildings not being all-electric ready. A May 2021 report by StopWaste for the California Energy Commission, “Accelerating Electrification of California’s Multifamily Buildings,” notes that, “Existing electrical infrastructure can be one of the biggest barriers to installing high efficiency electric space and water heating systems,” and adds that upgrading electrical capacity, wiring, and space configurations might prove prohibitively expensive and only addressable with robust incentives. A 2020 Urban Green Council study, “Going Electric: Retrofitting New York City’s Multifamily Buildings,” says the advanced age of much of the city’s multifamily structures almost guarantees that electrical upgrades would be needed, a costly, upfront obstacle to fully electrifying them. “New York City’s multifamily building stock is old; more than half was built over 80 years ago,” the report states. “The electrical service in many of them was designed long before today’s modern appliances and codes. These buildings would benefit from an electrical upgrade, and many will require one if their owners decide to switch to heat pumps.”

Existing single-family homes, a possibly target-rich environment for communities crafting de-carbonization plans, also pose an electrical infrastructure challenge. Electrical panels in many older homes may not be sized to accommodate a homeowner’s desire to go all-electric, especially if substantially more load is added when, for example, home EV charging demand is factored in. In that case, boosting the capacity and capability of the home’s electrical system via a panel upgrade might be a non-negotiable prerequisite.

Charles Cormany, executive director of Efficiency First California, a trade organization that represents home performance and energy efficiency contractors in the state, which leads the nation in the numbers of jurisdictions pushing for electrification, says the possible need for widespread electrical upgrades in existing homes is a wild card in efforts to extend electrification initiatives beyond new homes — and an issue that demands attention. Read the article, “Are We Overlooking the First Step Toward Electrification?” for more information.

“Many homes built pre-1990 in the state probably have 100A to 125A panels, whereas newer home construction standards are at least 200A,” he says. “That can be a barrier to going all-electric for those older homes because they’re not even up to handling the loads we’re putting on today. An upgrade can easily cost $3,000.”

Facing that cost, which even utilities eager to push customers in the direction of energy efficiency rarely if ever subsidize, many homeowners otherwise interested in transitioning to all-electric might face too big an obstacle. That could put the ball in the court of jurisdictions pushing electrification; any public subsidies for that in the form of rebates or tax credits for appliances, for instance, might have to also factor in costs to upgrade residential electrical service.

For now, governmental efforts to de-carbonize are mostly focused on new properties, not transitioning existing ones, and the locus of activity is California (see Fig. 1). That doesn’t mean they’re being overlooked, however. In Sacramento, Calif., for instance, the governing body adopted an ordinance in June requiring new homes, low-rise apartment buildings, and commercial structure to be fully electric by 2023. Additionally, the ordinance calls for the city by 2022 to craft a strategy for retrofitting existing buildings to all-electric by 2045.

Anticipating more eventual moves to bring existing structures under electrification mandates in the state, The Building Decarbonization Coalition, a group pushing to accelerate electrification, makes special note of the electrical panel upgrade issue. It says such upgrades might be necessary to make the switch, but notes that workarounds may exist, such as load-sharing circuit breakers and energy use reduction strategies that incorporate more higher efficiency equipment.

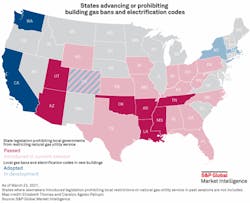

As more communities across the country push for electrification, there’s also a growing groundswell of pushback — some of it preemptive. A growing number of state legislatures, for example, are enacting or introducing legislation to block or limit moves to mandate de-carbonization, setting up a possibly protracted tug-of-war that could stall progress on electrification initiatives (Fig. 2). Should electrification ultimately gain steam, though, efforts to transition existing buildings could rival those to ensure new structures conform. And that could translate to a new set of expanded and extended opportunities for electrical professionals.

“There’s a niche market that’s starting to develop in California for electrification services,” Cormany says. “Savvy electricians might try to start getting ahead of the curve by supporting electrification, evaluating the electrical service status of clients and talk about the benefits of upgrading to support electrification plans and also enhance overall electrical safety.”

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].