The Lagging Transition to LEDs in Schools – Part 2 of 3

Interrelated changes are likely to affect schools’ use of fluorescent lighting across the country in the near timeframe. Regulations that effectively ban fluorescent lamps are spreading. Users are reducing the demand for fluorescent lighting. And manufacturers are reducing the supply.

Increasing regulation

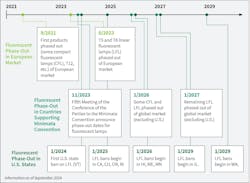

The European Union completed its prohibition on the sale of fluorescent lamps in 2023, based on mercury content. Although the ban does not affect manufacturing for the North American market, it does signal the direction for fluorescents and may influence the speed of phaseout.

In November 2023, 140 countries agreed to prohibit the manufacture and import of linear fluorescent lamps, also due to mercury content. Limitations on certain lamp types are already in place, with regulations for general linear fluorescent lamps slated for 2026 or 2027. The United States is exempt from this ban due to eliminating other mercury-containing products; however, this prohibition is also influencing state legislation and manufacturing.

State legislative actions to eliminate linear fluorescent lamps (outright or effectively) are increasing (see Chart). So far, 10 states have laws on the books or under consideration. Vermont has already prohibited all linear lamps, and, in January 2025, lamps cannot be sold in four more states (California, Colorado, Oregon, and Rhode Island). While some of the facility personnel interviewed were already aware of these legislative initiatives, other facility staff may be unpleasantly surprised when fluorescent lamps are no longer available.

Diminishing demand

Fluorescent lamps generally cost less than LED replacement lamps (TLEDs). As the cost difference narrows, one significant barrier to adoption lowers. In some markets, there is no LED premium; however, there is a fluorescent premium.

Some of the school facility personnel interviewed by PNNL stated that inexpensive LED products now make it economical to switch to LEDs when the ballast fails on a fluorescent luminaire. Others noted that the price of emergency fluorescent ballasts has increased considerably, and some components are harder to find, including specialty ballasts, T12s, and 8-ft T8s. Schools are also challenged with fluorescent recycling, both as an additional cost and staff responsibility — creating another reason to move away from fluorescents.

Utility incentives for LEDs fluctuate state by state, with some states sunsetting rebates, such as Oregon, where rebates are ending in July 2025. Some local utilities only provide incentives for TLEDs and not for other replacement options while some utilities are shifting focus to incentivize lighting controls. Where utility rebates were available, two out of three schools we interviewed took advantage. Some schools PNNL spoke with paid less than a dollar for a TLED post-rebate — well below the price of a fluorescent T8 lamp and disposal fees.

The influence of price on demand is dynamic. Competition remains stiff among LED manufacturers, limiting price increases. At the same time, falling demand and constrained supply are likely to increase the price of fluorescent components. Price is already shifting some schools away from fluorescent lamps, further reducing demand.

Diminishing supply

In the face of legislative action and declining demand, manufacturers are cutting back on the production of fluorescent lamps and luminaires. One announced in August that production would end in 2027. Another manufacturer has moved production of U.S.-compatible lamps from the United States to India and Poland, reduced the number of products available, and more recently announced price increases. Others have moved production to China.

Relocating fluorescent production to lower-cost offshore manufacturing reduces both factory overhead and direct labor — savings that are offset to some degree by higher transportation and inventory costs. Cost reduction, combined with increased price leverage, sustains fluorescent profitability. Companies are likely to stay in the market as long as it makes financial sense.

In addition, fluorescent luminaires are disappearing from the market even faster than lamps. Luminaire manufacturers large and small have exited the market or curtailed product availability. When the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) released its Energy Conservation Standards for Fluorescent Lamp Ballasts (a publicly available document), a public comment from the National Electrical Manufacturers Association (NEMA) indicated that none of its manufacturers were investing in fluorescent ballast technology and that product R&D had shifted to LED technology as of 2020.

As LED luminaires now dominate new building construction and major renovations, the cost of maintaining fluorescent product availability will continue to rise. At some point, diminishing economies of scale will end (or substantially reduce) the production of components unique to fluorescent systems. Of course, specialized manufacturers may produce replacement components in limited quantities and at high cost. But this is hardly an answer for schools maintaining old fluorescent systems.

What’s the outlook?

From 1990 to 2010, the substantial standardization of linear fluorescent lighting has helped school maintenance personnel keep their systems operating with modest cost and trouble. In this sense, fluorescent lighting systems are a familiar and comfortable option. That is until schools can no longer secure lamps, ballasts, and other critical components. Then what?

Some forecast that fluorescent lighting will effectively disappear in about five years. In this view, the combination of legislative pressure and the diminishing profits from shrinking sales will lead manufacturers to exit the market for fluorescent lamps and concentrate all efforts on LED products.

Industry data from NEMA show that from 2015 to the middle of 2020, linear fluorescent lamp sales showed a steady 67% decline, except for a small bump in late 2019. For the next two years, sales were generally flat. Fluorescent ballast sales also fell by 70% from 2015 to 2019. By comparison, TLED sales peaked in 2018 and have generally declined since.

If fluorescent lamp sales continue to decline at an estimated rate of 20% annually over the next five years, the market will have fallen by another 67%, leaving sales at just 10% of the pre-LED rate. For schools needing a reliable and economical supply of replacement lamps, this looks like the effective end to fluorescent lighting in the United States.

Of course, once the end is near, we will likely see schools weighing whether to jump in and accomplish the upgrade quickly or to purchase the remaining fluorescent inventory and postpone the cost of the changeover — simply acting as they have been until they can’t anymore.

The next article in the series considers upgrade options available to school decision-makers but with tough decisions and trade-offs that consider both short- and long-term outcomes.

About the Author

Jessica Kelly

Jessica Kelly is a lighting research engineer at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Andrea Wilkerson

Andrea Wilkerson is a lighting research engineer at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory.

Dan Blitzer

Dan Blitzer is principal of The Practical Lighting Workshop, a consultancy in marketing and education for the lighting industry.