Promise Vs. Practice: Are Lighting Controls Closing the Gap?

When lighting controls moved past the simple switch, a gap began to grow between the technology’s promise and practice. Controls promise energy savings, convenience, and tailored lighting effects. But the post-installation reality includes systems that don’t function as intended, controls that have been disabled, and costs that significantly exceed expectations. What’s more, over the last decade, enhanced controls capabilities have increased system complexity, which has served to maintain the gap and (in some cases) widen it.

Most of us have experienced the struggle between what we want (more capabilities) and what we don’t (more complexity). In the dynamic U.S. market, the capabilities/complexity tradeoff remains. But several developments look favorable for improvement. Most of the observations shared in this article relate to projects with discretion or significant influence over the choice of a lighting control system. Whether you’re responsible for electrical engineering and construction or working to a consultant’s specifications, your choices and advice can improve the effectiveness of lighting controls in terms of cost, performance, and reliability.

Upgrade, not replace.

At Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, we have begun to see manufacturers creating scalable systems (Fig. 1) rather than separate control products — each targeted to projects of a different scale (i.e., think room-based vs. networked). In general, a scalable system starts with a common platform and by adding components, such as a gateway, the system can grow in scale to handle an entire building and even a campus of buildings.

oth owners and contractors. Controls that satisfy simpler requirements can be upgraded as requirements change without the need to replace the original installation. A scalable system permits rightsizing of the control system at the outset, which reduces the initial cost, complexity, and risk of failure. The knowledge and know-how that went into the first installation should give the installing outfit a leg up in securing the upgrade.

A common platform brings consistent system architecture and terminology to a manufacturer’s products. Designers and installers don’t need to learn as many new arrangements and technical descriptions. Training is more efficient because installers and project managers do not need to master as many separate products and configurations. With familiar terminology as the system grows in scale, communication on the job is less likely to be misunderstood.

Scalable systems can be fundamentally more cost-efficient than a series of independent systems; you can build on them rather than replace them entirely. There’s less material and labor waste as the installed components remain in use when the system is upgraded. There’s also less “knowledge waste” in learning a new system architecture, installation process, and protocols. Of course, a scalable system does not necessarily mean a simple one. Today’s lighting control systems continue to add capabilities. Usually, the more capable the system, the more costly, complex, and risky it becomes. The simplicity of a buildable system lies in its ability to be upgraded (rather than replaced) as project needs change.

The information you need

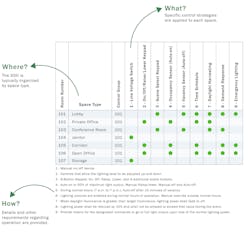

Industry practice is changing, particularly for controls documentation. Familiar wiring and riser diagrams have long guided installers in the installation and connection of lighting control devices. But where is the information you need to set up the system after installation? A Sequence of Operation (SOO), a common practice in the setup of HVAC and other mechanical controls, has now been applied to lighting controls, as shown in Fig. 2.

Previous practice left many ambiguities and gaps in information: Controls might not perform as intended, and there was no documentation to guide the fix. The SOO can serve as a roadmap for setting up a control system. In a well-written SOO, you can find the specific settings for each function in each control device. The SOO provides a format for collecting such information as time-out periods for occupancy sensors, light levels for dimmers and different scenes, set points for daylight harvesting, and scheduled lighting change.

Large projects typically engage a commissioning agent for setup. For smaller projects, setup may be a designer’s responsibility or service provided by the control’s seller or manufacturer. Sometimes, setup falls to the installer — or simply falls through the cracks. Here’s where the SOO can save time and money.

The Illuminating Engineering Society has published LP 16 Documenting Controls Narratives and Sequences of Operations. Among its many important features, LP 16 shows how the various controls documents work together and offers examples of different formats and methods for creating a clear and complete SOO. Several examples apply to projects where lighting controls are engineered within the electrical contractor’s scope.

All-around support

Just as the number and capabilities of lighting control systems have grown, so has the availability of information, training, and support. Installers can use their smartphones to download apps with installation and setup instructions. Installers can also watch videos showing how it should be done. The best setup guides are built into the app itself.

Manufacturers provide training on their own products, of course, but organizations like the Lighting Controls Association (LCA) offer generic training. The LCA catalog currently includes 33 separate classes available online, ranging from 100-level courses, such as Occupancy and Vacancy Sensors, to the more advanced Luminaire Level Lighting Controls and Lighting Control Protocols.

You can also attend seminars dedicated to lighting controls at trade shows and conferences around the country. In addition, you can draw local support from the increasing number of controls specialists in lighting sales agencies, especially those that have proved most effective. In other words, there is no shortage of resources to help close the gap between promise and practice.

Capabilities first

Why are systems installed with low-priority features that complicate the system and add cost and risk? Perhaps customers fear missing out on a feature that might be of use later. With their practical knowledge and experience, electrical firms are well-positioned to help customers assess the value trade-off as more capabilities add cost and risk.

New tools make it easier to focus system capabilities and rightsize the system. After years of observing the selection and installation of lighting systems, PNNL has developed materials to assist in system selection, beginning with objectives (Fig. 3). In addition, the DesignLights Consortium recently updated its Qualified Products List of networked lighting controls. The QPL features a searchable database with filters for various capabilities.

Looking at system capabilities before purchasing products familiar to you — with their known feature sets — helps to rightsize the system. With a capabilities-first approach guiding the choices, it becomes easier to choose among the favored brands and suppliers that best fit your business approach. Rightsizing becomes routine.

For most projects, “code compliance at least cost” provides the starting point for system design or selection: just a few capabilities, including occupancy control, scheduling, daylight response, bi-level, or dimming. Of course, the details vary by code jurisdiction. For many customers, the control system can start and end with the code requirements.

For others, additional energy-oriented capabilities, such as high-end trim or energy reporting, can offer an attractive return on investment. Perhaps scene controls or tunable white lighting will enhance the appeal or productivity of high-profile areas. And some customers believe that advanced sensors and analytics promise productivity gains in the facility.

Much of the challenge with system selection lies in the intangibles of products and suppliers: reliability, familiarity, and responsiveness. Most businesses deal with a favored brand or outfit because experience says that it saves time and money. On the other hand, sticking to a favored brand can limit important options and information. Moreover, it may diminish competition, raising costs.

Searching the DLC Qualified Products List and thinking “capabilities first,” as discussed above, can now provide the information to focus system selection on those systems with the optimal range of features.

It’s within reach

Although the gap between promise and practice may never disappear entirely, I now see it narrowing, thanks to these developments — all of which bode well for the bottom lines of both electrical firms and customers as well as others in the industry. Scalable systems can increase flexibility and reduce wasted equipment and training. Improved documentation can avoid many costly problems in system configuration. Rightsizing can lower cost, complexity, and risk of failure. Taking a capabilities-first approach can help find the favored brand best suited to the project.

But it won’t happen by itself. To enjoy the promise of profits from lighting controls, electrical professionals must build a technically knowledgeable workforce and adopt new practices. In this sense, you are another key to closing the lighting controls gap.

Ruth Taylor serves as a project manager on the Advanced Lighting Team at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory where she leads projects including Next Generation Lighting Systems (NGLS), a nationally recognized program that encourages technical innovation and promotes excellence in the design of energy-efficient LED luminaires and connected lighting systems. Feel free to share your experience with lighting controls with her at [email protected].

About the Author

Ruth Taylor

Ruth Taylor serves as a project manager on the Advanced Lighting Team at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory where she contributes to multiple projects, including the management of Next Generation Lighting Systems (NGLS), a highly successful, nationally recognized program that encourages technical innovation and promotes excellence in the design of energy-efficient LED luminaires and connected lighting systems. She can be reached at [email protected].