Opportunities and problems often go hand in hand, and public electric vehicle (EV) charging is no exception. One big opportunity is the $5-billion U.S. National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Formula Program, which is funding 500,000 EV chargers at locations, such as rural interstate travel stops. It’s a major reason why the research firm Wood Mackenzie expects the installed base of public chargers to match the residential market by the end of this decade.

All that means plenty of business for electrical contractors serving the EV market — including residential — because people are more likely to buy an EV if they’re confident that they’ll be able to charge it when they’re not at home. In a 2022 Consumer Reports survey, concerns about public charging availability were the top reason why people wouldn’t purchase their first EV.

One problem is that not every public charger charges. In a University of California analysis of 678 chargers at 181 stations in the Bay Area, only 72.5% worked. When the researchers rechecked 10% of them eight days later, not much had changed.

“This level of functionality appears to conflict with the 95% to 98% uptime reported by the EV service providers (EVSPs) who operate the EV charging stations,” the researchers said. “The findings suggest a need for shared, precise definitions of and calculations for reliability, uptime, downtime, and excluded time, as applied to open public DC fast chargers (DCFCs), with verification by third-party evaluation.”

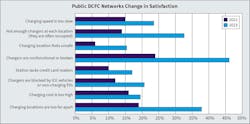

According to a report released by ChargeX Consortium, “Customer Experience at Public Charging Stations and Its Effects on the Purchase and Use of Electric Vehicles,” consumer satisfaction with DCFC networks declined sharply in the last year (see the Figure below) based on survey data from J. D. Power and Plug In America. The most-widely cited issue for public DCFC networks related to “nonfunctional or broken chargers.”

Funded by the Joint Office of Energy and Transportation, the National Charging Experience Consortium (ChargeX Consortium) consists of three national laboratories (Argonne National Laboratory, Idaho National Laboratory, and the National Renewable Energy Laboratory), which collaborate with organizations representing a cross-section of the electric vehicle industry to address three EV charging challenges: payment processing and user interface, vehicle-charger communication, and diagnostic data sharing.

Raising the bar for uptime

The California study was conducted in early 2022, but there are several reasons why the findings are as relevant as ever. One is the requirement that NEVI-funded charging stations have 97% uptime.

“We have to report the uptime, as well as many other things about the charging stations,” says Kim Okafor, general manager of zero emissions solutions at Trillium Energy Solutions, which builds and operates EV chargers for its parent company, Love’s Travel Stops. “Kudos to the federal government on that. Their intention is to put in a charging system that will work for the consumer, and the way they’re doing that is holding NEVI [recipients] accountable.”

Some states also are tying funding to uptime.

“In California, the charger reliability act requires all publicly funded chargers to have a certain uptime,” says Amaiya Khardenavis, a Wood Mackenzie analyst who covers EV charging infrastructure.

Privately funded chargers are exempt from state and federal uptime requirements. Even so, their owners will be under competitive pressure to maximize uptime to avoid having a bad reputation among EV owners.

“We want to be seen as the charging network that always works every single time you come to it,” says Okafor, whose company is among the top three NEVI funding recipients.

More money for more maintenance

NEVI recipients can use some of their funding to cover maintenance costs for up to five years. Electrical contractors could offer those services directly to charging station owners in their area or by working with nationwide service providers, such as ChargerHelp and EverCharge.

“We can’t cover the whole country, so we’re constantly looking for partners,” says Jeffrey Kinsey, EverCharge vice president of engineering.

Besides the NEVI program, the growing number of EVs on the road is providing charging operators with more money for more maintenance.

“Utilization has gone up,” says Khardenavis. “They are making money. There are better margins. And now those margins can be invested back into maintaining the charger. What used to happen is that because there was no money being made, there was no impact on them to really maintain chargers. It was burning cash, so a lot of times that was neglected.”

The maintenance opportunity isn’t limited to contractors in cities and suburbs, where most public chargers currently are. The NEVI program prioritizes underserved areas, particularly the rural highways where EV owners’ range anxiety kicks into high gear. So, one type of potential beneficiary is a small-town contractor that’s within, say, a 60-mile radius of two interstate travel plazas with a dozen chargers each.

“Local contractors can quickly come, quickly diagnose, and quickly get it back up and running,” Okafor says. “That’s where electricians play a huge part in making sure that we have a really high uptime. The analysis we’re doing right now is, what’s the best way of making sure that we have the right contractors in our ecosystem?”

One way is by simply adding chargers to the existing maintenance framework used for lighting, HVAC, and coolers.

“[The manager’s service request] goes to a local electrician that’s tied to that store and says: ‘You have so many hours to get there. And if you don’t get there in so many hours, we have a back-up person,’” Okafor says. “We’re not trying to reinvent the wheel. We figured it out for the rest of the store.”

That includes gas pumps, which highlight the business case for regular maintenance.

“It’s no different than fuel dispensers: Everything requires maintenance,” says Karl Doenges, executive director of the Transportation Energy Institute’s Charging Analytics Program. “It’s uptime not because it’s built so darn robustly [but] because it’s maintained properly. And when it does go down, you have someone within miles that has inventory and a truck and can roll wheels immediately.”

Navigating the charger market

Most public chargers are Level 2 or Level 3, also known as DCFC. The latter’s higher power requires much more complex chargers, which means more aspects to troubleshoot and maintain. But market share is another important factor when deciding what to focus on.

“A DC system is just wildly complex,” says EverCharge’s Kinsey. “It is a beast of a unit. To keep a system running, Level 2 is much easier. [Also] there aren’t that many DC contracts going on out in the world. The projected growth of DC is pretty small, and because of the extreme voltages, that’s not something that a common electrician is going to be doing anyway.

“On the other side, the opportunity for Level 2 is substantial. You see DC showing up at pit stops or malls, but you see Level 2 showing up at every workplace, every hotel, every apartment building, every condo complex. There’s just a lot more financial opportunity to work on Level 2 versus DC.”

The charger maintenance market also has a thicket of proprietary manufacturer hardware and software.

“There is a lack of standardization across the industry,” says Wood Mackenzie’s Khardenavis. “Every charger model and every software-hardware combination are different. There are so many players [because] we are not at the stage of consolidation yet. It becomes tougher for training electricians on so many different types of hardware and software.”

The ChargeX Consortium was created to mitigate those challenges. One initiative is a standardized set of minimum required error codes (MRECs) that all charger manufacturers would use to streamline troubleshooting. Available at https://inl.gov/chargex/mrec, the 26 MRECs cover a wide variety of fault types, such as voltage and temperature excursions, ground failures, and loss of internet connectivity.

“It’s not an exhaustive list in the sense that these are the only error codes that service technicians will see,” says Benny Varghese, who leads the ChargeX Consortium diagnostics task force for EV charging infrastructure. “On top of this minimum set, each manufacturer can have their own specific error codes that will depend on the technology they’re using and different kinds of sensors they have, which is fine. All we’re recommending is that they at least have enough sensors and enough telemetry to be able to detect these particular errors. If you really want to give more information, you are welcome to add other error codes.”

Some problems are due to the EV or its driver rather than the charger.

“An error code could be thrown out, but it’s hard for somebody debugging it later on to realize that the error is from the vehicle side or from the charger side or somewhere else,” Varghese says. “So, there’s also a responsibility classification in terms of which entity is responsible.”

Another maintenance opportunity is weights and measurements certification. With fuel pumps, certification involves ensuring that each pump is dispensing exactly what the customer is paying for. The same concept applies to chargers, except the measurement is kWh instead of gallons.

Weights and measurements are governed by states rather than the federal government. The bigger the charging network, the more jurisdictional requirements its operator has to understand and meet.

“That’s something that we’ll be leaning on our contractors for,” says Love’s Okafor. “Who would know better than a contractor that regularly works in that jurisdiction?”

The need for speed

For operators, another major challenge is lining up all of the necessary electrical equipment and utility service so the chargers are ready to go when a new travel stop or shopping center opens. This problem creates at least two opportunities for electrical contractors.

The first is serving as a dry utility consultant to determine whether the grid can handle the chargers. This role requires a deep understanding of each utility’s requirements and capabilities in all of the areas where the contractor wants to offer that service.

The second potential opportunity is designing, installing, and maintaining solar and battery energy storage systems (BESSs). Depending on the number and types of chargers at a site, solar and BESSs could provide enough additional power to cover what the utility can’t.

“The market is very creative, and we’re seeing a lot of companies offer solutions to work around this,” says Transportation Energy Institute’s Doenges. “One of them is battery storage systems. That will allow stations to move faster. You have some more upfront cost with the battery, but that’s offset by less electrical work, permitting, and other things.”

Depending on the type of business hosting the chargers, another potential selling point for BESSs is the ability to support more than just chargers.

“BESSs can also be used as a backup to the store, especially if you’ve got perishable items or a beer cave,” Doenges says. “You have those things go out of temperature range, lose the inventory, and that gets expensive. Fuel dispensers run on electricity. If you have a natural disaster and lose power, having the battery system allows you to run those, as well.”

BESSs also could be attractive in markets with utility demand charges because it enables arbitrage.

“You have algorithms and software that track the demand cycles, so you can run low before evening for the tariff change,” Doenges says. “Then you fill up the whole thing overnight [so] you can dispense lower cost electricity during peak hours of the day.”

Even if solar can’t provide enough power to support the chargers, it still could be a worthwhile investment by enabling the project to qualify for carbon tax credits and other incentives. The panels also could double as canopies, which most EV charging stations don’t have, unlike fuel pumps.

“A lot of areas will shift to a canopy anyway,” Doenges says. “Why not put some put solar panels on top? It will help generate carbon credits.”

That option is one more example of how the public EV charging opportunity is even bigger than it appears at first glance.

“There’s going to be a lot of work for electricians,” Okafor says. “We want to make sure that we are working with the people that really know the rules and regulations in that area — both on the design-build side and the operation and maintenance side.”

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].