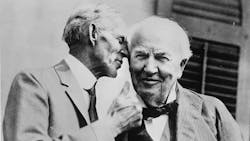

Henry Ford and Thomas Edison were friends for half a century. When he’s making presentations about fleet electrification, Rajiv Singhal includes a slide with a photo of Ford whispering into Edison’s ear. “It’s like he’s saying, ‘Our two industries are going to intersect,’” says Singhal, who leads the zero emissions transportation team at 1898 & Co., Burns & McDonnell’s consultancy subsidiary. “And that’s what’s happening. Transportation never spoke utilities, and utilities never spoke transportation — and now they have to speak those two languages. This picture (Photo 1) is from 1925 (almost exactly 100 years). Who would have thought this was going to happen?”

But these days, fleet electrification projects often feel like they’ll take another century to complete. Although the selection of electric delivery vans, terminal tractors, trailers, buses, rental cars, and trash trucks keeps growing, charging remains a significant roadblock — not just long charging times and the paucity of public chargers, but also the difficulty getting them installed at the business’ own facilities.

“Charging infrastructure may be one of the longest lead time components of our decarbonization plan for last-mile delivery vans,” says one executive, speaking on background, whose company currently has chargers at more than 100 of its depots nationwide.

Electrical contractors and design firms are turning this problem into a business opportunity by identifying ways around some of the roadblocks so projects can move forward rather than being shelved. In addition to helping clients, some firms also are extending this consultancy role to electric utilities for grid planning. In fact, one common hurdle is whether the local electric utility can provide enough power to a site to charge dozens or hundreds of EVs.

“Utility lead times continue to be one of biggest challenges facing this industry,” says Geri Waack, director of eMobility solutions at EnTech Solutions, a division of Faith Technologies Incorporated (FTI). “We’ve seen providers have power available almost immediately, while others have lead times of 18 months or more.”

In some cases, the necessary infrastructure isn’t in place because the client’s facility is in a remote area, such as a sprawling new logistics park on the outskirts of town where land is cheaper. Closer in, the nearby substations and lines often are maxed out.

“I’ve heard places where they’re saying it can be three years before they get a connection,” Singhal says.

Alternatives to an alternative

Electric utility-related challenges, such as grid constraints and demand pricing, have some fleet owners considering workarounds to keep their electrification plans on track (Photo 2). Later, some of these short-term solutions can be expanded and upgraded for the long haul if they make good business sense.

“Alternative energy options, such as solar, battery energy storage, and microgrids, allow clients to offset utility demand and pricing, as well as create grid independence,” Waack says.

Lenexa, Kan.-based Henderson Engineers currently has two projects where the required amount of power is several miles away.

“They’re having to bring in new utility lines that far to supply the load,” says Clif Orcutt, electrical technical manager. “So, we are considering doing some on-site battery storage for other reasons, as well, one of which is to offset the utility peak demand. It’s not enough to totally account for all the EV charging, but the owner can expand on that later if they decide that it’s worth the investment.”

One deciding factor is how many EVs need to be charged.

“Solar does not cut the [utility] bill because, depending on the fleet size at that given site, it may not be enough solar to fulfill that demand,” says 1898 & Co.’s Singhal. “Battery storage is expensive. It’s good for peak shaving. But if you have to run an operation for, say, eight hours, batteries will be very expensive.”

Even for major businesses, a battery energy storage system (BESS) capable of charging dozens of vehicles can be cost prohibitive.

“From what I’ve seen, the installed cost is about $1 million for a megawatt,” Orcutt says. “That is definitely a barrier to entry, and that’s not including the cost of the solar panels to charge those batteries. PV [photovoltaic] has been around for a while, and batteries have too. But specifically in this application, batteries are the newer technology — so it’s tough to get a price on those at this size.”

Code evolution affects options

The National Electrical Code (NEC) provides guidance about sizing a system.

“It’s a rather straightforward calculation: however many [chargers] you need times the load of the charger, and that’s what the Code is going to make you do,” Orcutt says. “You have to take 125% of that because, in some cases, it’s considered a continuous load — meaning it goes longer than three hours.”

The Code is evolving in ways that affect fleet electrification, but opinions vary about whether those changes help or hurt.

“If anything, the Code has gotten more stringent about EV charging instead of more accommodating,” says EnTech’s Waack. Some changes worth noting include the following:

- Section 625.42: Elaboration on charger management software and engineers’ ability to downsize services and feeders if it is used.

- Section 625.44(B): Expanded allowable amperages for mobile chargers.

- Section 625.49: Allows “island mode” where EV chargers are allowed to export power and operate off-grid.

- Section 625.54: Requiring GFCI protection on receptacles used for EV charging; leads to more expensive but safer installations.

Others say Code changes are providing flexibility that could make some projects viable.

“The latest NEC is starting to build in compliance methods that include a load management system,” Orcutt says. “Basically, a control system says: ‘We’ll never charge more than X.’ If there are too many chargers plugged in at once to do all of that load at 100%, either they stagger some on or off, or they reduce charging on all of them.”

Some systems can provide additional flexibility by managing other electrical devices around a facility rather than just the chargers. For example, if a garage door opener isn’t in use, the allotted amperage load for that device can be redirected to the charging station. When someone needs the garage door to open, the control system will respond by decreasing the power flowing to the charging station.

Sometimes, load management systems can make one location more viable than others (Photo 3).

“The client may come to you with six sites they’re considering,” Orcutt says. “We do a study to tell them for each, here’s what the utility can handle at this time frame, and here’s how we can bring in load management technology to maybe make this site work in the short term rather than years.”

The larger the load, the more likely the project will require a dry utility consultant, which works to ensure that all the necessary utility infrastructure and capacity are ready to go.

“A dry utility consultant knows the [local] utility requirements in and out,” Orcutt says. “We coordinate through them with the utility. It’s more prevalent on the West Coast from what I’ve seen, mainly because those utilities have a lot more strict requirements. It’s kind of almost a specialty.”

This process can include striking a balance between supply and demand.

“We can have discussions with utilities on how the business plans on charging their vehicles on a schedule, let’s say, and how that interacts then with the other electric loads happening on the grid at that same time,” Orcutt says. “There can be an agreement that gets made there as far as the capacity of equipment and power delivered to the site. Instead of looking at just one block [of time or] peak demand number, you’re looking at more of the energy profile through a day and/or through a year.”

The range factor

Each type of fleet has its own business drivers for electrification, but some apply across the board.

“From a cost and operational standpoint, fleet operators are motivated by the potential for long-term cost savings on fuel, maintenance, and operational expenses, as well as increased operational efficiency due to their quiet operation, reduced maintenance needs, and improved efficiency in stop-and-go traffic,” says Jeffrey Kinsey, vice president of engineering at EverCharge. “EVs are also becoming more accessible and available, and government incentives, tax credits, and grants for EV adoption are also playing a role in encouraging fleet electrification.”

Some types of vehicles are better candidates for electrification than others because of how and where they’re used. For example, terminal tractors move trailers around a seaport or logistics park but never take them across town or across the county. So a transportation company might choose to electrify its terminal tractors first because they’ll always have access to chargers on site.

The business case for local delivery vans and long-haul trucks is more challenging. At a November 2023 conference, J.B. Hunt Vice President and Chief Sustainability Officer Craig Harper summarized the pros and cons.

“We have five today, and drivers love them,” he said. “They are quiet and powerful, but there are problems. You don’t have the range; that is one-fifth of what diesel provides. It also weighs more, and it takes longer to charge.”

Harper also cited research showing that 21% of public charging stations are down at any given time — a big barrier to adoption that gets even bigger when you consider that there aren’t that many to begin with. As an October 2023 EC&M story found, major truck stop operators such as Love’s are struggling with many of the same challenges as their customers: getting enough power and demand charging. That’s why some truck stop operators are considering solar and BESSs.

Another barrier to the electrification of long-haul trucks is that truck parking is in chronically short supply. That’s why so many drivers resort to camping out on highway on and off ramps when they reach their federal hours-of-service limit.

“A big portion of today’s truck parking network — about 40,000 spaces — is at rest areas on the interstate where commercial activity isn’t allowed,” says Jeffrey Short, American Transportation Research Institute (ATRI) vice president. “That’s a federal law, so there aren’t going to be chargers at those locations anytime soon.”

Rental ripples into residential

Electrification in the passenger vehicle market is further along in terms of selection, adoption, and public chargers, but it’s still a niche compared to internal combustion engines (ICEs). That could give rental fleets another reason to add even more EVs — and benefit electrical contractors serving the residential market. For example, in November 2021, Hertz ordered 100,000 Teslas to make 20% of its fleet electric. However, in more recent news, Hertz announced it was selling about 20,000 electric vehicles (including Teslas) from its U.S. fleet as EV demand cools.

“Data from IHS that says that people have a tendency to rent cars to try new technology, so it makes sense that rental cars should be electric,” says Ben Prochazka, executive director at Electrification Coalition, which partnered with Enterprise on a study into the EV rental market.

The rental electrification trend also could spur even more demand for home chargers.

“Rentals tend to be big volume sellers in the used car market,” Prochazka says. “That creates an opportunity for used EVs to be much more available.”

Besides growing consumer interest in renting EVs, another driver is government incentives for fleet owners.

“In the Inflation Reduction Act, there are big incentives for charging infrastructure: up to $100,000 available on a per-unit basis,” Prochazka says. “That’s going to help reduce some of those cost barriers that might exist in the short term. Some states have additional infrastructure incentives or additional vehicle incentives, like in California, where they have an additional tax credit that’s available. Colorado [is another] example.”

Finally, some electrical contractors and design firms are leveraging their fleet electrification experience to help utilities plan grid upgrades that need to accommodate more than home charging.

“Lots of utilities are asking us today: ‘Tell me about this new EV load and how/what can I do to prepare myself. I need to build the rate case plan. I need to put [in] infrastructure for the next five, 10, 15, 20 years,’” says 1898 & Co.’s Singhal.

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].