Alarm bells continue to sound about a looming shortage of electrical engineers. The latest warning comes in a report from The Information Technology and Innovation Foundation (ITIF) on electrical engineering degree trends and their possible impact. The D.C.-based institute that focuses on the intersection of technology and public policy says statistics point to a slowing pace of U.S. university degree awards in that discipline, evidence of declining interest, especially among those likely to end up employed in the United States. That’s worrisome, ITIF says, because demand for electrical engineers is high and will continue to grow as public/private technology and infrastructure investment soars.

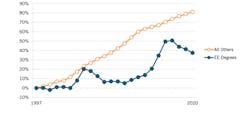

Citing U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Census Bureau data, ITIF notes EE degree awards rose 38% between 1997 and 2020, far behind the 81% growth in all other bachelor’s and master’s degree awards (Fig. 1). From 2009 to 2021, holders of EE degrees aged 18 to 30 rose 22% compared with 36% for all other degree holders. In its calculation, the statistics mean that “the young adults that will drive the economy in the coming years are studying something other than EE.”

More pointedly, within the engineering field EE may be losing out to other disciplines. The report posits that an EE degree pursuit may be particularly daunting for those interested in engineering broadly, leading many to avoid it up front or eventually abandon it. “The combination of higher standards, strict grading, and often poor teaching means students have strong incentives to either not enter the EE major or switch majors,” the report reads.

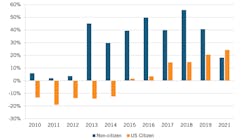

A growing proportion of those who do pursue and attain an EE degree are those from other countries who come to study in the United States, the report notes. With degree in hand, many end up returning to jobs in their native countries or otherwise leaving the United States, leaving domestic employers to compete intensely for the smaller cohort of graduates ultimately available to them. “From 1997 to 2020, the number of EE bachelor’s and master’s degrees awarded to U.S. citizens grew only 18.2% compared with 110% among temporary residents,” the report states (Fig. 2).

The implications of ITFI’s insights, along with others that have pointed to declines in the pool of trained electrical engineers, are varied for would-be employers. Some EE degree specialties, such as computer engineering, may be less affected because of the steady lure of careers in the digital universe, while power systems could struggle because of what has been ebbing interest in grid-related engineering work. But firms engaged in a broad swath of electrical engineering and design work — from MEP to power generation to control systems — almost certainly stand to be affected by any fading interest in the field among would-be engineers.

Brian Leavitt, director of electrical engineering at IMEG, Rock Island, Ill., says the pool of newly minted electrical design talent the company seeks has been getting shallower over the last decade. He attributes some of that to the appeal of employment in other specialties, notably computer engineering.

“Good talent is available but difficult to find sometimes,” he says. “The explosion of so many shiny items in engineering has absorbed a lot of talent.”

But jobs IMEG offers may be starting to entice more electrical engineering graduates, Leavitt says, because electrical design is becoming more varied, interesting, vital, and perhaps secure. With more tech companies in layoff/hiring freeze mode currently, he observes, graduates may be more open to alternative engineering career paths that aren’t as clogged with degree holders and seekers.

Firms needing talent may ultimately have to come up with strategies to adapt to fewer electrical engineering graduates. One may involve training and educating more non-EE grads in electrical once they’re on the job. Relatedly, firms may have to hire more graduates with other types of degrees.

Henderson Engineers, Lenexa, Kan., is steadily hiring more graduates with architectural engineering degrees, says Jason Wollum, chief sector officer. They bring a broader knowledge set that can include enough electrical understanding to get them positioned for design work and deeper on-the-job learning, he says.

“You’ll find architectural engineers alongside electrical engineers at many firms these days,” he says. “It’s a growing offering from many university engineering programs that provides more specialization in building systems design that includes electrical.”

Yet IFIT insists nothing is likely to replace the university-trained electrical engineer. That’s why its prescription for the shortage it sees building includes a stronger role for government.

“Policymakers should provide incentives for colleges and universities to keep expanding EE enrollment for U.S. citizens and permanent residents while also working to increase retention rates in EE programs,” it says.

Tom Zind is an independent analyst and freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].