Understanding Three Essential Elements of Electrical Distribution Systems

As electrical professionals, it’s important to have a basic understanding of several design criteria that are important to the design, operation, and maintenance of electrical distribution systems. These include, but are not limited to, short circuit, selective coordination, and arc flash calculations.

Short Circuit

The short-circuit current rating (often referred to as short circuit or fault current) is defined by the National Electrical Code (NEC) as “the prospective symmetrical fault current at a nominal voltage to which an apparatus or system is able to be connected without sustaining damage exceeding defined acceptance criteria.” This value represents the maximum amount of energy that should be available at any given point in an electrical system. This energy can be manifested in various forms. Therefore, electrical distribution equipment must be selected to withstand this calculated energy value at each point in the system. If the system is not designed to handle the available energy, severe damage to life or property may occur. This value is listed as the short-circuit rating and is often identified in units of KAIC (thousands of amps of interrupting current).

To calculate the available short circuit throughout an electrical system, the first step is to determine the maximum available current at the facility’s service connection point. This starting value can then be used to calculate values at any point in the distribution system. As you move downstream through the system, the available short-circuit value will be reduced, as this current is opposed by impedances that it encounters on its way. These impedances include the conductor length, conductor size (cross-sectional area), conductor material (typically, copper or an aluminum alloy), and the raceway type. Transformers also contribute impedance in a circuit. After all this data is compiled (lengths, sizes, material, raceway type, and transformer impedances), it is then used to perform calculations to determine the fault current at different points in the system. There are several ways to calculate these impedance contributions and the resultant short-circuit levels at different points in a system.

The most widely used method on larger systems is to use large-scale electrical distribution system analysis computer programs. Most of these programs can also be used to perform coordination and arc flash analysis, along with voltage drop calculations. Short-circuit calculations can also be performed using some software tools available online (mostly in Microsoft Excel format) or even by hand.

Selective Coordination

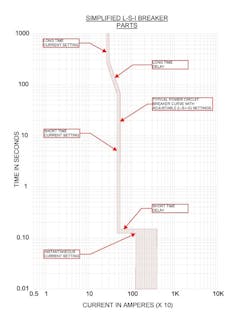

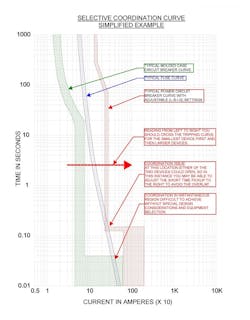

Selective coordination is defined in the NEC as “the localization of an overcurrent condition to restrict outages to the circuit or equipment affected, accomplished by the selection and installation of overcurrent protective devices and their ratings or settings for the full range of available overcurrent, from overload to the maximum available fault current, and for the full range of overcurrent protective device opening times associated with those overcurrents.” In other words, the overcurrent devices in an electrical system should ideally be designed to open the device closest to the fault or event. This helps to prevent nuisance trips of unaffected portions of the system, which could lead to facility downtime. For example, if a fault on a 20A branch circuit trips a 1,200A main breaker, a large portion of a building/facility would experience a preventable power loss. To get a distribution system to operate in this manner, you need to compare and contrast the electrical characteristics of each overcurrent device in the system.

Selective coordination is required per the NEC on emergency and legally required standby systems. It is not required on other portions of the electrical distribution systems in the building. However, its implementation is recommended. Typically, when selective coordination is not required by code — but is implemented regardless — it is not implemented to the full range of overcurrents. Coordination in the instantaneous range is difficult to achieve due to the inherent breaker properties. Typically, coordination in this range requires special design considerations and often involves upsizing of equipment or the use of adjustable electronic trip circuit breakers.

To perform proper coordination studies, the exact electrical distribution system equipment needs to be known. Every breaker and fuse have different properties and react differently. In addition, installed feeder routing can alter the impedance contribution of the wiring. Basis-of-design equipment can be used preliminarily to provide a working solution for bidding purposes. However, a final study will need to be performed once final equipment is selected.

See Fig. 1 and Fig. 2 for an example of time/current curves and an explanation of how they work together.

Arc Flash

Short-circuit and coordination studies are important on their own, as previously described. However, arc flash information also plays an important role for a facility.

Short-circuit and coordination calculations need to be completed to perform arc flash calculations. As noted on the OSHA website, “An arc flash is a phenomenon where a flashover of electric current leaves its intended path and travels through the air from one conductor to another, or to ground. The results are often violent and when a human is in close proximity to the arc flash, serious injury and even death can occur.” Arc flash is of great concern, as it can be a great danger to maintenance staff. It is highly recommended that all electrical equipment be de-energized prior to opening, but this is not always an option. If someone does need to work on energized equipment, it is important that he or she be aware of the potential arc flash risk, and be aware of the available potential energy so that proper procedures and protective equipment can be used.

Arc flash energy values are based on two major factors: the available fault current at a particular point in a system and the speed at which the overcurrent protection device (OCPD) clears the fault. Fluctuations in either of these items could increase or decrease the available incident energy. Incident energy is defined by the Glossary of Environment, Safety, and Health Terms (2006) by the U.S. Department of Energy, as: “The amount of energy impressed on a surface, a certain distance from the source, generated during an electrical arc event.” Therefore, if the fault current is low, it is possible that the OCPD would not operate as quickly as if the fault current was higher. This would lead to higher incident energy than if the current was higher and allowed the OCPD to operate more quickly. While arc flash calculations can be performed by hand or using simple software tools, they are typically performed using large-scale electrical distribution system analysis computer programs.

During design of electrical systems, it’s important to be cognizant of this relationship between fault current and clearing time. Systems can be designed to limit available incident energy, hence making the system safer for maintenance personnel. This helps illustrate why performing short-circuit and overcurrent protection device coordination studies are an important part of the design process.

There are methods available to help limit arc flash hazards. The NEC requires a method of arc energy reduction be implemented when circuit breakers in electrical distribution equipment reach a certain size. The most common methods involve either limiting the amount of available fault current or shortening the reaction time of the overcurrent protection device upstream. The most widely used method to shorten the reaction time is to use an arc energy reduction maintenance switch, which temporarily changes the settings of the circuit breaker, allowing for faster operation, hence reducing available arch flash energy. Other methods include, but are not limited to, high-resistive grounding, zone selective interlocking, differential relaying, and energy reducing arch flash mitigation systems.

Cleis is a vice president with Peter Basso Associates, Inc., Troy, Mich. He can be reached at [email protected]. Gibbs is also a vice president with Peter Basso Associates, Inc. He can be reached at [email protected].