Construction Labor Productivity Trends 2024

Construction is a labor-intensive business. Despite tremendous advances in design, coordination, and management technologies, the physical installation of work in the field remains reliant on people. Of the nearly $900 billion in construction put in place by labor-intensive contractors in the United States in 2022, FMI research suggests contractors lost approximately $30 billion to $40 billion due to labor inefficiencies. At the individual contractor level, these labor productivity deficits translate to project and enterprise margin erosion.

Labor productivity is a challenge for the construction industry, and it appears to be getting worse. FMI’s 2023 Labor Productivity Study confirms the well-documented trend of productivity decline, with only 23% of respondents claiming labor productivity improvements over the last 12 to 18 months. Almost half of respondents (45%) saw declining labor productivity, and a third saw stable labor productivity trends in their businesses.

The study explores the major challenges that must be addressed to improve productivity for the industry, including both internal and external obstacles that contractors face in their pursuit of performance optimization. Additionally, FMI identifies key management practices and traits of high-performing contractors, including planning behaviors, project controls and support for the field. To produce these findings, FMI surveyed more than 250 senior leaders from labor-intensive, self-performing contractors in the summer of 2023 to understand productivity challenges and best practices.

Productivity drives profitability

Contractors believe 11% to 15% of field labor costs are wasted or unproductive. Although it is unfair to expect contractors to reduce their waste or unproductive time to zero, respondents conservatively believe that 6% to 10% of labor spending ($15 billion to $25 billion) could be saved through better management practices.

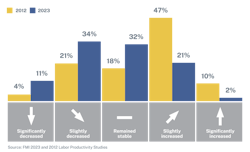

In 2012, 57% of those surveyed by FMI said productivity had slightly or significantly improved. By 2023, that figure fell to 23% (Fig. 1). Similarly, in 2012, only 25% said productivity had slightly or significantly declined, and by 2023 that figure increased to 45%.

Humans are the biggest driver of putting work in place, so it’s no surprise that many of the top challenges (either internal or external) uncovered in the survey were directly related to people. First and foremost is finding skilled workers, especially in the field. As FMI’s 2023 Talent Study revealed, 93% of firms can’t find the workers they need, with the biggest gap in talent associated with field leadership.

The labor productivity study backs that up with 63% of respondents citing lack of qualified craft labor as the No. 1 internal factor impacting productivity. After a lack of labor, contractors said their top internal struggles were associated with poor planning and communication by field management and project management as well as subpar project team collaboration and site logistics.

How to solve the labor productivity problem

Here are a few factors that are within a contractor’s control to influence the outcome with it comes to job-site efficiency.

Project labor budget performance

Contractors are in the labor-management business, and understanding labor costs has a clear, direct effect on profitability. One of the ways FMI assesses the overall efficiency of labor-intensive contractors is how regularly they meet or beat estimated labor budgets.

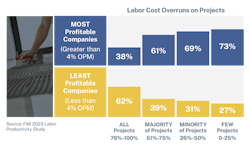

When projects overrun on labor budgets, project margins suffer. If project labor overruns are a common occurrence, enterprise profitability suffers. This obvious connection between labor performance and profitability is confirmed through contractor feedback in the study. Those firms with fewer labor overruns tend to be more profitable.

Avoiding labor overruns on a singular project can be managed by experienced project and field leadership. However, avoiding labor overruns at scale across a large number of projects requires organizational standards for proactive planning and project controls (Fig. 2).

Planning is critical

Projects that fall behind early rarely make miraculous recoveries. The discipline of in-depth, collaborative field and office planning before mobilization (pre-job planning) is one of the greatest influences on labor productivity.

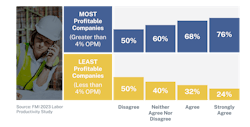

FMI’s data shows that the earlier field leaders are involved — and the better prepared they are before mobilization — the higher the profit margins. The percentage of contractors with operating profit margins (OPMs) greater than 4% steadily increases along with their field teams’ levels of readiness (Fig. 3). However, field managers who shoulder the stress of on-site execution are particularly susceptible to burnout. FMI research found that executives expect 30% turnover for field managers over the next five years, which means that keeping staff engaged and providing the right support will be crucial.

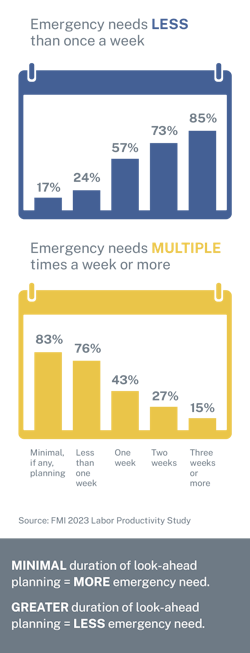

In Fig. 4, the study compares the duration of look-ahead planning and how frequently field managers have resource emergencies. Results show that the further out contractors plan, the fewer emergency events they have every week. Of the contractors that do minimal planning, 83% have resource emergencies multiple times a week, while only 15% of contractors that plan for three weeks or beyond have resource emergencies multiple times a week.

Cost-to-complete forecasting

In addition to field leader preparedness and detailed look-ahead planning, the accuracy of cost-to-complete (CTC) forecasting correlates with higher profit margins. Cost forecasting discipline is a key marker of contractor maturity and sophistication. Contractors that can accurately forecast their costs know where their projects stand and what it will take to finish the job.

That level of confidence requires accurate tracking of installed quantities and labor hours from the field, reliable cost reporting, and strong communication between field managers and project managers.

Building a better future

Not surprisingly, 70% of contractors in the study highlighted improving planning and execution practices as their top priority for adjusting operations over the next 18 months. For best practices on what top-performing companies do right, see “What Top-Performing Companies Do Right.”

Additionally, leadership training and development was the second-highest priority listed.

Contractors that establish sound operating processes and train their people to be successful in their systems perform better than their peers. This takes significant time and discipline. If done well, however, it can have a significant impact on the bottom line and improve employee engagement and retention.

By getting a handle on productivity, giving workers the tools needed to be successful and diligently planning for jobs, companies can improve margins and profitability. In an industry where one bad job can make or break a company, harnessing the power of your biggest asset — your people — will ensure you continue to successfully operate and thrive.

What Top-Performing Companies Do Right

- Pre-job planning: This requires consistent and thorough translation of project information from estimating to operations, followed by in-depth planning by project teams to develop strategies for optimizing labor productivity and project performance.

- Look-ahead planning: This needs a weekly cadence of field leaders communicating resource needs (labor, equipment, materials, subcontractors, and information) for upcoming activities to be coordinated and supported by project management.

- Daily goal setting: Field leaders establish and communicate clear, quantifiable production expectations and objectives for crews daily.

- Labor productivity tracking and feedback: Field leaders and project teams need regular reporting of productivity information in digestible formats so they can discuss project performance and detect labor risk early. This requires well-vetted budgets with hours and quantities before mobilization, accurate reporting of time and quantities by field leaders throughout the project, and reinforcement of the right behaviors.

- Cost-to-complete forecasting: This critical report is based on a monthly analysis of the costs incurred to date, the percentage of the job that is completed, accurate forecasting, and re-estimating the cost to complete the remainder of the scope of work. Accuracy of the cost-to-complete forecast increases with up-to-date direct cost accounting, early buyout and locked-in pricing, field input on the remaining work and accurate productivity tracking that can be utilized to project labor costs.

- Exit strategy: During this phase, the project team meets to re-energize, focus, and develop a plan to finish a project on time and mitigate the risk of late project margin fade. This would typically occur when the project is near 80% completion.

- Post-job review: After project closeout, this meeting shares and documents the lessons learned, provides production feedback to estimating, and captures trends for future success and continuous organizational improvement.

About the Author

Michael Keller

Michael Keller focuses on providing expert guidance on strategic planning, productivity and operational excellence. He helps organizations recognize maximum operational potential and find data-driven, proactive solutions to complex problems. Before FMI, Michael spent several years in commercial construction project management, completing projects ranging from minor tenant improvements to large health care projects. Michael can be reached at [email protected].

Tyler Pare

Tyler Paré leads FMI’s Performance practice, which helps contractors optimize profitability and manage risks. His team focuses on the major performance drivers for contractor organizations – operations, risk management, compensation and technology – helping client organizations secure and execute work profitably, pay and incentivize people effectively, and collaborate and share information efficiently. As a consultant with FMI, Tyler leverages his construction experience and business knowledge to assist contractor clients in implementing work acquisition and project execution best practices in support of competitive strategy. Tyler also facilitates contractor executive peer groups, which bring construction industry leaders together to collaborate and learn from each other. Tyler can be reached at [email protected].

Jake Howlett

Jake Howlett is an analyst in FMI’s performance practice where he focuses on facilitating data analytics processes for client deliverables and internal projects. His expertise is in front-end analysis and backend data process development. While obtaining his master’s degree he engaged in data consulting projects as part of capstone projects. Jake also comes from a construction background, working for his family construction business in the private wellness, pool and spa industry. Jake can be reached at [email protected].