Pay hikes are solid, bonuses are commonplace, the work is satisfying, and employer support is strong. Yet work/life balance seems out of kilter, it’s harder to keep up with the cost of living these days, the economy is a nagging concern, and staffing issues are worrisome.

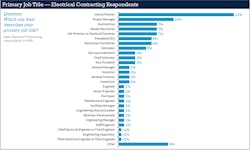

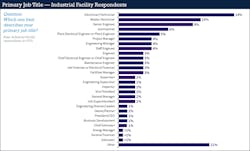

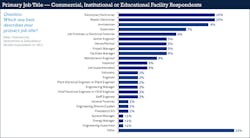

That’s a quick summation of the findings of EC&M’s 2023 Electrical Salary Survey and Career Report. But then there’s this nugget: One-third of electrical professionals who work in roles like electrician, engineer, company owner, C-suite executive, and manager (Fig. 1 through Fig. 4) indicated they would not be inclined (many without reservation) to recommend that a child or young close relative pursue a career in the electrical field (Fig. 5).

Shocking? Perhaps, given the pay, status, and relative security that comes with many job roles in this sector — and more so since EC&M’s inaugural survey on compensation and career satisfaction in 2019 found only about 7% indicating they wouldn’t recommend the electrical field. So what happened?

Maybe times have changed. A life-altering pandemic, the Great Resignation phenomenon, higher inflation, back-breaking educational costs, and a reassessment of what’s important in life may have also intervened. Many workers have taken a step back, looked at their lives, and lamented paths not taken or reimagined their futures — and maybe glimpsed those of their loved ones as well — with a calculating eye.

But a wider lens has many of the 1,333 professionals surveyed saying life in the electrical world trenches is pretty good on balance and possibly getting better — at least in the short term. Whether it’s in the realm of total compensation, overall job satisfaction, or perceptions of employer sensitivity to their work and personal life needs, a hearty majority of respondents give their lot a thumbs up. And to be clear, even when it comes to that question about recommending a career as an electrical professional, most indicate they would.

“Sanguine,” then, might describe the mood of these professionals — and for good reason. In an economy where energy and its management are an increasingly vital and complex centerpiece, their unique skills, knowledge, and expertise are in demand — and they like that feeling. But with their ranks thinning and the talent pipeline narrowing, they’re being asked to bear more burdens — and that’s taking a toll on mood. Yes, compensation has improved, but inflation is eroding its value. Looking ahead, the market for electrical professionals’ services will be strong, boosted for many by more infrastructure spending, and the rewards could be outstanding.

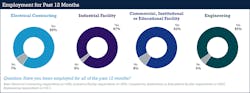

In the new survey, views on compensation and job satisfaction break along professional sector lines, sometimes sharply. Respondents came from four arenas employing electrical professionals, each of which has its distinctive internal dynamics that affect pay, benefits, and working conditions, unionization and education/training being important variables: electrical contracting (600 completing survey); industrial facility (269); commercial/institutional/educational (221); and engineering (243), as shown in Fig. 6.

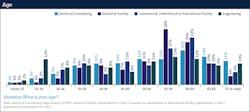

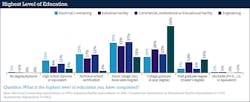

Cross-sector, almost all were employed full-time (Fig. 7) and had been steadily employed the prior year (Fig. 8). They worked at firms of all sizes but skewed toward smaller among electrical contractors and engineering companies and larger among those at industrial and commercial/institutional/educational (CIE) workplaces (Fig. 9). Nearly all were male (Fig. 10), and a solid majority were clustered in the 50- and 60-plus age groups (Fig. 11). Most have at least some post-secondary education or degree (Fig. 12), and the vast majority hold some sort of professional certification (Fig. 13).

COLAs, labor market sweeten pay

Driven by rising inflation, low unemployment, and strong competition for labor in an economy where labor participation rates have been falling, U.S. employers have been raising pay to hire and retain workers. And those that employ electrical professionals haven’t been spared the angst of signing cost-of-living-adjusted (COLA) paychecks that look a lot fatter over a year and positively rotund compared with four years ago.

Indicative of the spot many electrical contracting firms working in construction may find themselves in, 86% of construction firms surveyed by Associated General Contractors raised base pay rates in 2022. Half were offering incentives or bonuses to secure workers, while a quarter were beefing up benefits packages.

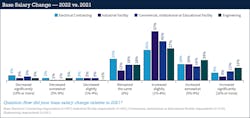

A plurality of those polled in the EC&M survey indicated that between 2021 and 2022 their base salaries went up in the 1% to 4% range (Fig. 14). The high end of that range is where a recent WorldatWork survey of U.S. businesses found mean and median salary increases settling in both 2023 and 2024.

More industrial professionals reported an increase (81%), while the electrical contracting cohort, consisting of a quarter each identifying as owners or presidents and electricians, had the fewest reporting a hike (63%). More engineering firms reported hikes at the top range of 10% or more (15%).

In the 2019 survey, respondents were reporting comparatively stagnant wages. Then, 32% of electrical contracting sector workers reported receiving no salary boost in 2018; this year 25% reported no change in the prior year. Discrepancies were similar in other sectors. With the percentage reporting prior-year pay cuts similar in both years — 8% on average — more pay boosts surely explain the difference.

Those reporting a pay hike — 75% of the sample — attributed the boosts to a mix of possible factors (Fig. 15). But cost of living, job performance, and standard company policy drew by far the most mentions from a list of eight possibilities. Those three factors were the top reasons in the 2019 survey, but cost of living had far more mentions this year — all but confirming that workers have been beneficiaries of inflation-influenced pay policies employers have had to institute to stay competitive in the labor market.

On average, 38% of respondents cited cost of living as a reason for the 2018 boost; in 2019, it was mentioned by only 25%. Generally, slightly fewer this year said promotions, new skill development, or added responsibilities were pay raise factors. Top write-in reasons included new union pay pacts, new contracts, more work, and a change in employers.

The small share of respondents saying their 2022 salary decreased from 2021 — most prevalent among electrical contractor and CIE staffers — cited various reasons, few a likely result of outright pay cuts (Fig. 16). Roughly half attributed the reduction to at least one of three possible factors: economic conditions that impacted employers, new lower-level position, or new company. The other half said there were “other” reasons; some specified among them were “retirement,” “reduced hours,” “less overtime,” and “insurance costs.”

More join the 100K club

Steady pay boosts that have been ramping up in the labor economy over the past several years have brought some notable changes to the reported salary ranges of electrical professionals (Fig. 17). A handy measure — those making over $100,000 in base salary — shows that these workers have made pay gains, some of which were significant.Averaging the four sectors, the share making over that amount increased 12% between 2019 and 2022. Those employed in the industrial sector showed the biggest gain in $100,000-plus earners — from 30% to 52%. The CIE worker share went from 21% to 32%; engineering from 51% to 59%; and electrical contracting from 34% to 40%.

On another scale, median reported salary ranges for both 2022 and 2023 for all sectors increased or stayed steady compared to 2019 survey results. The median range for professionals working for electrical contractors was $80,000 to $89,000, in line with 2018 when the mean salary was $87,588. Also in line were engineers, with $100,000 to $109,000 being the statistical middle group, the range 2018’s mean salary of $103,985 was in. But the median range for industrial facility electrical professionals whose 2018 mean salary was $82,185 rose from $80,000 to $89,000 to $100,000 to $109,000, and the median for CIE workers, whose 2018 mean was $77,155, ticked up to $80,000 to $89,999.

With inflation and low unemployment still bearing down, employers appear “willing” to throw more money at workers. But there are signs the pace may be slowing as inflation cools and the labor market softens amid growing recession worries. Some of that flux showed up in 2022 and 2023 salaries reported in the survey. While roughly similar, the pay range breakdown appeared to shift slightly higher over that period for electrical professionals.

The biggest change was in the share of engineering sector workers making $100,000 and up (Fig. 18). Sixty-two percent reported being in that group with their 2023 base salary, up from 59% saying their base was $100,000-plus in 2022. Percentages in that tier for the other three sectors were little changed. Top earners continue to cluster in the engineering and industrial sectors; between 14% and 20% of those professionals sit in the lofty $150,000-and-up class in both years, at least double the share in the other two sectors.

Bonuses sweeten the pot

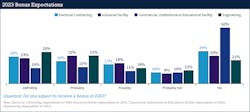

A sharp divide is also evident in another element of compensation that employers have embraced: bonuses. While slightly more than half overall said they got one in 2022 (Fig. 19), roughly two-thirds each in the engineering and industrial settings got one, but only one-third in CIE did. Electrical contractor respondents were split down the middle.

But bonuses are now a bigger part of compensation. In the 2019 survey, 43% of respondents overall said they got a bonus in 2018. That’s seven percentage points lower than in 2022. But bigger gaps are evident in three sectors: industrial, where just 43% got a bonus in 2018, compared with 62% in 2022; electrical contracting, 40% compared to 51%; and engineering, where it was 55% compared to 63%. Only CIE had a lower spread than the overall, 29% compared with 35% in 2018.

Bonus amounts in 2022 also varied by sector (Fig. 20), but the mean range overall fell roughly in the $2,000-$2,499 range. Sector highlights include one-third clustered in the $2,500 to $7,500 range for engineering, where the mean range was $2,000 to $2,499; 17% in the $20,000-and-up range for an electrical contractor, which had the highest mean range of $2,500 to $4,999; the most equal dispersion evident in industrial, which had a mean of $2,000 to $2,499 but a quarter clustered between $2,500 to $7,500; and 60% not exceeding $1,500 in CIE, where the mean was $1,000 to $1,499, the lowest.

Most surveyed think employers will continue to be generous with bonuses. In all but CIE, about two-thirds see some chance of one in 2023 (Fig. 21), with the highest confidence (67%) in engineering. Only 40% of CIE respondents have any level of confidence they’ll see one. Half say they don’t expect one — the highest share by far.

Core benefits vary

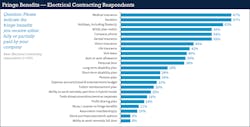

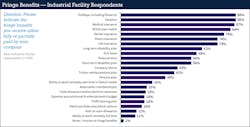

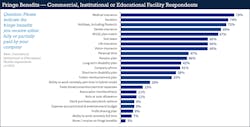

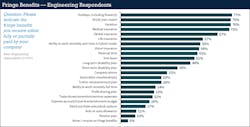

Gains on the pay front have been accompanied by some progress — or at least minimal losses — on the fringe benefits side. Among common benefits listed (Fig. 22 through Fig. 25), the leading ones and those around at least half say they get — 401(k) plan matches, holidays (floaters included), life, medical, dental and vision insurance, sick leave, and vacation — have increased in mentions since 2019. Benefits that are down in prevalence include personal time, trade show/convention/seminar expenses, and company phone.

As with salary and bonuses, the survey found some notable differences in access to benefits by employment sector: Electrical contracting respondents were generally less likely to say they get a listed benefit, and that group had by far the highest share (11%) saying they get zero fringe benefits. For 10 of 22 listed benefits, including 401(k), holidays, medical insurance, vacation, and personal time, more than half of engineering and industrial workers said they were receiving them, followed by eight for CIE and six for electrical contracting. Industrial and engineering stood out from the others, most starkly from electrical contracting, with notably higher numbers in 401(k), holidays, personal time, disability plans, and vacation.

An emerging fringe benefit is the ability to work away from the office. While remote and hybrid arrangements — combined office and remote work — took hold where feasible out of necessity during the pandemic, they’ve since receded, but far from disappeared. Their appeal among workers (and even among some employers) has endured, making them negotiable perks in many workplaces.

But among electrical professionals, the ability to work from home either full time or in a hybrid capacity, each an option added to the list of possible fringe benefits, is either not broadly sought or not available — unless you’re in engineering. Less than 10% of workers in electrical contracting, CIE, and industrial say a full-time remote work arrangement is offered, and fewer than a quarter say a hybrid one is available. With engineering workers, though, the numbers are 25% and 54%, respectively. That gap is understandable because unlike tasks electricians and many others who work in contracting, CIE, and industrial perform, many in the engineering world are readily adaptable to digital- and virtual-only platforms.

The low number of contracting, CIE, and industrial workers reporting the availability of remote work arrangements could mean many workers have seen them snatched away. Annual surveys of electrical contracting and electrical design firm professionals by EC&M have found they were commonplace during the pandemic but have since tailed off.

Worries aplenty

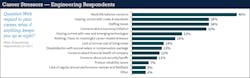

The loss of that perk for those who had it — and may have liked it because it made their lives more manageable — could partly explain why this year’s salary and job satisfaction survey finds “work/life balance concerns” rising sharply to the top spot on a list of possible nagging career-related worries. From a list of nearly a dozen possible things “that keep you up at night,” (Fig. 26 through Fig. 29) it was ranked No. 1 across all sectors, drawing mentions from 43% on average.

That’s not surprising. The pandemic brought more attention to the work/life balance and employment conditions issue, and it has stuck. Human resources consulting firm Gartner, Inc., put efforts to equalize workplace flexibility on a 2023 list of workplace trends to watch. Having granted many desk workers remote work, employers will be looking to offer frontline workers more work schedule control and stability, more liberal paid leave, and more say in what’s worked on, how, and with whom.

Close behind work/life balance on the worry list were staffing issues (35% average); economy/inflation (33%); staying current with codes and standards (26%); staying current with new and emerging technologies (19%). Additionally, a trio of separately listed concerns closely linked to the issue of remuneration — satisfaction with salary/compensation; annual performance reviews/feedback; and annual cost-of-living raises — combined to produce an average of 36%.

The rankings offer strong proof that despite data showing rising salaries, attractive bonuses, and ample fringe benefits packages, pocketbook and working conditions issues remain top of mind. But they also show that there may be a lot of free-floating job- and career-related anxiety — maybe a lot more than just four years ago.

This year, around 17% checked the “I have no meaningful career stressors” box. That was seven percentage points lower than in 2019. Other comparisons are notable. Work/life balance concerns registered an increase of 10 percentage points over 2019; economy/inflation concerns, 15 points higher; staffing issues, 12 points higher; the challenge of staying current on codes/standards, 12 points higher; keeping pace with technological changes, two points higher; and concerns about job security/layoffs, seven points lower.

Demanding, but manageable work

The leading stressors seem to share a common thread: anxiety about the ability to keep pace — with the rising cost of living and rate and nature of change in their fields that could ultimately impact job security — without sacrificing a well-rounded life. On that top-line score, the survey finds electrical professionals are persevering and, thanks to seemingly supportive employers, ultimately finding that middle ground.

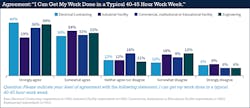

Though work/life balance tops the list of stressors, a core constituent of that — time spent on the job — seems reasonable to most respondents. Two-thirds strongly or somewhat agree they can get their work done in a 40- to 45-hour work week (Fig. 30), a slightly higher share than in 2019. The “strongly agree” group rose six percentage points. Electrical contracting and engineering workers scored notably higher on agreement in both years. Still, about 20% of total respondents disagreed in 2023, a slightly lower number than in 2019.

Likewise, keeping up with emerging technologies and codes and standards may be stress points for a fair number of workers, but most indicate they have resources that should help them cope.

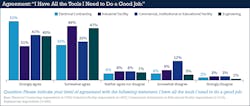

Some 80% at least basically agreed they “have all the tools I need (Fig. 31) to do a good job.” Though undefined, “tools” could mean anything from technology and resources to authority and physical tools. Engineering and electrical contracting workers were more likely to agree. And agreement took a jump from 2019. Then, only about three-quarters expressed some agreement that they had the necessary tools.

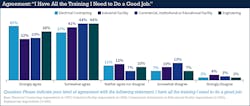

In the same vein, roughly three-quarters strongly or somewhat agreed they had all the training needed to do their jobs well (Fig. 32). Fewer industrial respondents agreed, while more engineers did. Another gauge of employer support, as well as the level of readiness a worker brings to the job, training is a factor that can influence a wide range of overall job satisfaction measures.

Angst aside, satisfaction reigns

On that big-picture front, despite ample areas of concern and stress, electrical professionals are mostly in accord. By wide margins, they say they’re not only content in their jobs, but they’re also passionate about what they do for a living.

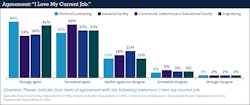

Those sentiments aren’t equally shared across sectors, but roughly three-quarters overall strongly or somewhat agree they “love their current job,” (Fig. 33) and an even higher share are similarly inclined to agree they’re “satisfied with their current position.” (Fig. 34) The share of CIE workers in agreement was lower than the others on both questions. Electrical contracting and engineering workers showed the most agreement. The findings overall were little changed from the 2019 survey.

But the share reporting very high levels of job satisfaction may not stack up to that of the general U.S. workforce. A recent Pew Research Center survey of U.S. workers found about half are extremely or very satisfied with their jobs; the EC&M survey found about 42% agreeing they were extremely satisfied. But in another comparison, a 2023 survey of U.S. workers from The Conference Board found 62% satisfied, the highest level since the survey began in 1987. That’s lower than the 80% of electrical professionals saying they were extremely or somewhat satisfied.

The ingredients for job satisfaction are many. On par with compensation for many is a sense of utilizing skills and talents in pursuit of attaining fulfillment, personal growth, and contribution. That comes through in the survey.

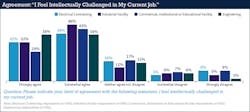

A solid majority strongly or somewhat agreed they “feel intellectually challenged” in their jobs (Fig. 35). That share has gone up since the 2019 survey, especially for electrical contracting workers, 61% to 71%. Across sectors, only about 10% voiced disagreement.

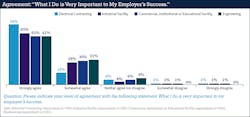

On the ultimate measure of job satisfaction, the one that creates the important two-way street that brings workers and employers together in pursuit of their goals, electrical professionals are of almost one mind. On the question of whether they feel what they do is “very important to my employer’s success,” 90% agreed (Fig. 36), most strenuously so. That percentage edged up from 2019 by around three percentage points on average. Moreover, it is much higher than the 62% who told the Pew survey they felt their employers valued their contributions either a great deal or a fair amount.

In coming years, success — hard-earned and fairly shared — could be ripe for the taking for many electrical professionals and the organizations that employ them. Highly trained and skilled electricians and engineers will be in demand and possibly in ever shorter supply as the profession battles an aging workforce and a dearth of new entrants. A growing and dynamic economy will look to their employers to execute projects that will be a bedrock of the infrastructure growth, ongoing maintenance, and energy transformation challenges ahead. The 2023 Electrical Survey and Career Report shows both parties are moving toward that promised land — maybe haltingly at times — but ultimately together and to each other’s mutual benefit.

Tom Zind is an independent analyst and freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].