Measuring and Improving Underbillings

Many of us live by and believe in the motto, “cash is king,” meaning that an overall positive cash flow will keep your business healthy and successful. Without positive cash flow, banks and other financial institutions may not allow you to continue to function.

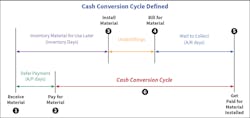

Cash flow is often measured via a cash conversion cycle. A long cash conversion cycle (CCC) means you’re funding jobs and even payroll from your pocket. A shorter cash conversion cycle reduces that issue and leaves cash available in the business for use as needed, including demonstrating business profits. Recognizing and improving under billings is key to improving your company’s cash flow. The best way to do this is not via accounting, which is often looking backward, it’s in the field — assessing where you are today and looking forward to what’s remaining.

What’s your CCC?

A graphic of the CCC is shown in Fig. 1. To explain the movement in the graphic, follow the circled numbers:

- You receive the material that you’ve ordered (this could be at the job site or in your warehouse or prefabrication shop).

- You pay for the material.

- You install or use the material

- You bill for the material

- You get paid for the material installed

The time between when you pay for materials and when you’re paid for installation of those materials is defined as the CCC. The longer this cycle, the longer you and your company are paying for this job. The knobs that are available to turn to reduce the CCC are your underbillings and your accounts receivables.

How are you billing and how does that impact underbillings?

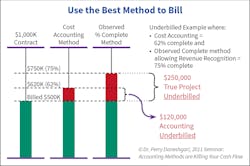

Before we talk about how to improve underbillings, it’s likely best to think through how billing is done and how you choose what to bill. Are you using the Cost-to-Cost method or the Observed Percent Complete method? It’s important, as the project manager/person doing the billing, that you bill based on the one that is higher. This will keep your cash flow higher. If you’re using the Cost Accounting Method when the Observed Percent Complete is higher than the costs, Fig. 2 demonstrates that you may be leaving money on the table

without recognizing it. An example is a $1-million dollar contract. The most obvious/known underbilling would be the difference between the $500,000 that you’ve billed and the $620,000 in cost you’ve spent. This is traditional accounting underbilling. This tracks costs spent to dollars billed. This is available by looking back into your accounting system. What you may be missing is: How complete is the work? Do not forget that with the Observed Percent Complete method through ASTM E2691, you can get paid for the pre-job and non-installation activities if you can track them and show how they contribute to fulfilling performance.

ASTM E2691 is the standard for construction productivity that uses Job Productivity Management (JPM). This begins at the job planning stage of the project and uses a work breakdown structure (WBS). Tracking against this WBS using the independent variable of work completed, the electrician can report the Observed Percent Complete for each task and recover revenue (including profits) for the actual percent completed on the job. The amount of true underbillings, per Fig. 2 on page 13, would be $250,000 instead of $120,000. It’s key to note that while accounting underbilling would show zero if you’ve billed $620,000, you are actually at $130,000 underbilled if you used the Observed Complete Method. Billing for this work is critical to your company’s success.

Linking the costs of underbilling and accounts receivable (A/R)

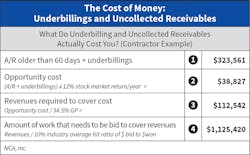

Using an example of dollars involved in the CCC, let’s see what the true cost of money is for your company. The Table on explains the work a company must do to cover for the underbillings and aged A/R.

- The amount tied up in A/R older than 60 days plus the underbillings in the company — you can modify this to your value.

- Opportunity cost: When money is not received, not only do you not have the actual money, but you also don’t have the use of the money. The stock market’s typical 30-year average return is 12% per year, so every month you do not have those funds, you’re losing market gains (or paying interest on lines of credit).

- Revenues required: Insert your gross profit number here. You must make additional money to pay for the money that is tied up in your CCC.

- It’s likely your estimating hit ratio is not 100%. The industry average is 10%. So, you have to bid 10 times the work to get a job that will give you the revenue to cover the money in your CCC.

What’s the lesson to be learned here? It’s critical that you reduce underbillings and collect on your A/R so that you do not have to tie up estimators and profits to cover this.

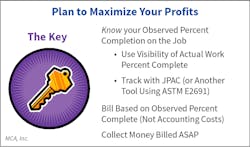

Make a plan to maximize your profits by measuring and improving your underbillings

The key to this equation is shown in Fig. 3. You must minimize or eliminate underbillings. Your accounting team must track company profits based on FASBs ASC606 for Revenue Recognition. If you are not billing for either Cost-to-Cost or Observed Percent Completion on the job, your company will show a loss. You must truly know your Observed Percent Complete by using ASTM E2691 Standard for Job Productivity Management on your jobs. Do this by walking the job and comparing the work breakdown structure that defined the work. Track this with a job productivity management tool. Bill based on that percent complete and then be sure to collect that money.

Jennifer Daneshgari is vice president of financial services at MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. She can be reached at [email protected]. Dr. Perry Daneshgari is president and CEO of MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Jennifer Daneshgari

Jennifer Daneshgari is the vice president of financial services at MCA, Inc. She can be reached at [email protected].