How to Maximize Your Money with Change Orders

Change orders, along with death and taxes, are certain in life. Throughout 30 years of working with hundreds of companies and projects, we have yet to find a single project that makes it to the end without a change order. However, all the studies conducted by our company, universities, and associations indicate that if change orders are not managed appropriately, they will actually cost more than priced — and are one of the main reasons for unanticipated productivity and job profitability losses.

How is this possible when our labor is priced higher to do the same work? We add more revenue for the same or slightly different work and still come out losing profit. Findings of the studies just mentioned can be summarized in the following three categories:

- Derailing the original project schedule and flow.

- Not recognizing and reporting these changes promptly.

- Extra labor cost is consumed by existing labor overage or productivity losses already present in the original scope of work.

In this article, we will explain how avoiding these side effects of any change order can help the project be more productive and profitable.

How to avoid derailing the original project’s schedule

Simply put, the changes you are asked to price are not the complete set of changes your installers must deal with. To avoid derailing the original project schedule, you must start with an original project schedule ― the schedule that matches your work, not the customer’s schedule that appears reasonable and doable. Without a thoroughly thought-out and written work plan (based on your scope of work, your deliverables, and your installation team’s input), you are already giving up productivity and profit from the original contract. Without a clear understanding of the work and developing a written breakdown of your plan of attack, your team will not have the tools or knowledge to recognize changes at the time they occur. You are at the mercy of your customer to offer you each opportunity to price changes. The only way you can effectively avoid derailing the original project schedule is to immediately detect and react to the changes as they occur — not after the added cost is recognized. A written work breakdown structure (WBS) is a tool that translates the field leadership’s tacit knowledge and experience into explicit knowledge that becomes the baseline that all field labor can use to recognize changes. If there is no common baseline expectation, then there is no way to detect a change from the expectation to report.

How to make change orders visible and track them promptly

Don’t be a victim. You are not a hostage to your field labor’s ability and/or willingness to report changes as they occur. Given the WBS, you should not only trust your employees to use it effectively, but also employ proven management methods and tools to verify and back up the field reporting activity. Eventually, your financial reporting will tell you how much you lost to unrecognized changes. However, by then it’s too late to recover the profit.

Your fastest access to change visibility is when labor recognizes the changes before they perform the work. The second is a productivity measurement that detects the reduction of productivity on the work planned in the original WBS. If the original plan was created efficiently and without excess buffers (i.e., sandbagging), then there is no opportunity for the field worker to spend their time performing other unplanned tasks without impacting the measurable productivity of the base work.

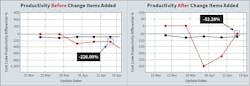

By using a measurement tool based on the ASTM Standard E2691, you will be able to quickly detect changes in productivity that result from unplanned work on your job, whether your labor recognized and reported the changes or not. To effectively use this tool to detect and mitigate pending profitability losses, you will need to develop and implement a process for measuring productivity against the original baseline budgeted hours plus all additional work associated with all changes to the base scope. Whether the changes are approved or not approved, they will need to be tracked to truly determine how effectively and efficiently your labor is performing against the baseline scope of work (Fig. 1).

How to manage the extra monies in the change order

All this planning to develop a baseline so that an informed worker and/or an intuitive software can detect and flag extra work is only the groundwork. Realizing increased profitability from change orders comes directly from managing both the work and the money associated with the change order in a way that translates into increased profitability without diminishing the profits of the existing work. Like all management functions, this too requires visibility into the workings of the production machine: the job.

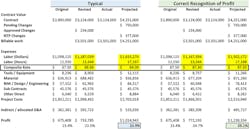

When a change order is granted, the contract value is revised, and additional labor is added to the project plan and WBS, we are at our most vulnerable. If we simply add the money and the labor, then that’s all we will have — more money and more labor. If we stop there, then often it is used just to cover the shortfalls of our previous bidding and selling negotiations and/or productivity shortfalls already present on the job. If we want the added profitability of higher-priced change orders to be reflected in our results, then we must remove the added profit from the revised cost. This is often more complicated than simply adding a larger revenue number than the associated incremental cost number. We need to rewrite the job profit to reflect the portion that is profit and not allow it to be consumed in the general performance of the base contract scope. Figure 2 demonstrates an example of this situation, which we will now walk through.

Let’s say the original bid labor was at a rate of $87.50 per hour (composite rate), and all change order labor is sold at a higher price of $112.00 per hour. This will create an additional contract value; however, how much of this is labor cost versus how much is additional profit needs to be accurately reflected. If the estimated costs are entered exactly as estimated, that additional labor rate dilutes the expected productivity of the revised contract work. This is shown by the impact on the composite labor rate for the entire project, including the original work. Because the overall composite labor rate increases to $94.09 per hour, the revised profit expectation only rises from 23.4% to 23.9%. However, if the added cost is considered profit, and labor cost is added at a consistent $87.50 per hour (same number of hours used in the change order estimate), then the profit expectation increases from 23.4% to 29.1%.

Additionally, consider that if material purchased for the change order is sold at a higher rate, then a similar erosion of profitability will occur if the higher material mark up associated with the change order isn’t removed from the revised material cost and added to revised profit. In jobs where there were significant post-bid material pricing negotiations and/or large jobs with special pricing for early purchase orders, this profit loss can become quite significant on even a small change order.

The last point related to money is tricky because the schedule impact needs to be known before the change order is actually priced, so it can be built in before passing it to the customer. When the change order is first detected — or when working outside of the original contract scope begins to impact the schedule of the original contract scope — then the cost of these impacts must be associated with the pending change order that you are pricing. In addition, if the change order (once approved) will result in additional impacts to the original schedule, then these pending base contract impacts also need to be priced as a part of the pending change order. Failure to recognize and anticipate these base impacts is the greatest reason why contractors don’t make money on change orders.

Using the combined information available from both the WBS and the productivity measurement is the only way to effectively know and project these impacts. Any means that does not rely on this level of planning, tracking, data, and analysis is simply guessing. Although this may work occasionally, it is not a repeatable and predictable process for estimating change orders or ensuring profitability from change orders.

Dr. Perry Daneshgari is president and CEO of MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. He can be reached at [email protected]. Phil Nimmo is vice president of business development with MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Phil Nimmo, MCA, Inc.

Phil Nimmo is vice president of business development at MCA, Inc. He can be reached at [email protected].