There’s code, and then there’s the Code. The perceived differences between the two help explain some of the challenges to filling the roughly 195,000 construction job openings in Q1 2021 — and that was before vaccinations turbocharged demand for new homes and new solar farms to power them.

When it comes to electrical careers, high school students and their parents don’t know what they don’t know. Their only experience with the profession is when they need a fan hung or an outlet replaced. So they don’t understand, for example, that electricians have to master a Code that changes significantly every three years. They also don’t see that electricians work with renewables and the Internet of things (IoT).

“The average person doesn’t know that,” says Mike Catalano, a master electrician who’s also a high school guidance counselor in Saugerties, N.Y. “They think you’re just pulling cable. They don’t think of it as high learning. I also think the mental model of physically working hard is taboo.”

By comparison, parents and students have a much better understanding of computer coding as a career path. One reason is the plethora of science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) initiatives at the local, state, and federal levels. Mainstream media stories about the chronic shortage and high wages of computer programmers, and Super Bowl commercials for Girls Who Code that spotlight the career opportunities for young women in particular, also drive awareness. All of that also influences guidance counselors, who — like parents and students — don’t know what they don’t know.

“We’re extremely influential for what kids choose for courses,” Catalano says. “We can steer them. But the majority of counselors I work with don’t come from construction or technical [backgrounds].”

Pro-college bias

There’s no shortage of high school career and technical education (CTE) programs, many of which include electrical. But there’s a catch.

“A lot of boards of education will gauge a principal’s success or failure based on how many kids go to a four-year college. It’s extremely frustrating,” says Catalano, noting that his school is an exception to that rule. “The current leadership here is very pro-technology, very pro-electrical and other hands-on [professions]. It’s been great.”

This pro-college bias is starting to get attention outside education circles.

“Mike Rowe says there’s a hurdle with the way counselors are graded,” says Bill Fowler, senior instructor and manager of industry partnerships at Southwire, a wire and cable manufacturer whose 12 for Life program works with local schools in Carroll County, Ga. “That’s a huge stumbling block. That’s where the secretary of education at the federal level needs to get involved and say, ‘We need to change this.’”

In the meantime, some change is underway at the state level.

“Maryland has taken a somewhat different approach,” says Grant Shmelzer, IEC Chesapeake executive director. “As a state, we’re making inroads into debunking those metrics by which schools are measured.”

Start ’em young

Lots of other industries are struggling to find people, so it’s worth looking at their initiatives for potential strategies. One takeaway is that while electrical typically focuses on high school juniors and seniors, industries such as telecom are introducing their career opportunities to much younger students. For example, Verizon’s philanthropic arm invested more than $100,000 in Indiana STEM programs that begin as early as the second grade. In Arkansas, the company funded a STEM camp for junior high girls.

This focus doesn’t surprise Harold Deloach, a master electrician who founded The Academy of Industrial Arts, which trains electricians in the Philadelphia area.

“One fact I learned when I worked for Associated Builders and Contractors is that the best age to get the spark of interest is around 8th and 9th grade,” Deloach says. “You have to get them early. The challenge is that there’s such a lack of vocational trade programs at the middle school level. There isn’t enough funding behind it.”

Catalano agrees.

“They shouldn’t have to wait until 11th or 12th grade to go to BOCES,” he says, referring to Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES), a New York State program that supports local CTE initiatives. “Kids need to start getting some exposure in elementary school. A lot of kids don’t see tech until they go to BOCES. So you don’t know what you don’t know.”

Limited budgets and staff also are barriers to building awareness among middle schoolers.

“If we had the resources and staff, I’d definitely do it,” says IEC Chesapeake’s Shmelzer.

Some contractors are filling the gap by working directly with local schools.

“They’ve been partnering with middle schools and high schools to bring in their own programs to plant the seeds early,” DeLoach says. “I think that’s great.”

San Jose, Calif.-based Cupertino Electric works with the IBEW to drive interest in electrical careers.

“We constantly look for ways to engage young people interested in construction by partnering with local unions at job fairs, participating in Associated Schools of Construction (ASC) student competitions, and supporting summer helper programs that give students insight and experience in the industry,” says Jeremy Flanders, director of field operations for data centers. “We also have a strong social media presence to interact with younger job-seekers on their terms.”

Alternatives to traditional learning

One reason why students don’t go to college — or struggle to finish high school — is because they don’t enjoy the traditional classroom model of learning. CTE programs cater to those students by providing a hands-on alternative to learning, but the catch is that most aren’t eligible until 11th grade.

“We lose that population because we’re not capturing them,” Catalano says. “So we have work to do there.”

To provide hands-on opportunities, Saugerties Central Schools partnered with Habitat for Humanity to build a home. Under Catalano’s guidance, students installed equipment such as a 200A electric service, a secondary underground residential distribution cable to a pad-mount transformer, recessed lighting, circuit wiring, and more. Look for an article on this project in an upcoming issue of EC&M.

“These students are using the electrical theory and knowledge of the NEC that they have learned in class and are putting it into real practice,” Catalano told EC&M earlier this year in a podcast.

In his presentation to IEC members last year, Fowler emphasized the opportunity to reach out to at-risk teens.

“All they need is some guidance and somebody to mentor them,” Fowler says. “Every high school in the U.S. has a work-study program. You can go to a high school counselor and [say]: ‘Who are those kids who really need help? Turn us into a mentorship and also a way for them to earn income.’”

Emphasizing the opportunity cost

One helpful trend is growing parental and student aversion to the five- and six-figure debt associated with a four-year degree. But to capitalize on that opportunity, electrical needs to educate them about the alternatives.

In its “Question the Quo” national surveys of Gen Z (age 14-18), the research firm ECMC Group and VICE Media found that “many high school students feel uninformed about the options available, with 63% of teens wishing their high school provided more information about the variety of postsecondary schooling opportunities available.”

Conducted in February 2020, May 2020, and January 2021, the surveys also found that:

- Only 25% believe a four-year college degree is the sole route to a good job.

- The pandemic’s economic impact has spurred interest in alternatives. Twenty-five percent say they’re more likely to attend a career and technical education school due to COVID-19, and another 29% say they’re less likely to attend a four-year college.

- Sixty-one percent believe a skill-based education makes sense in today’s world.

Another key finding is that their top three concerns are graduating with a lot of debt, not getting a job after they graduate, and not being prepared for a job after school ends. Apprenticeship programs are ideally positioned to address all three while leaving the door open to a college degree.

“Unlike the traditional college experience, students who get accepted into a union-affiliated apprenticeship program get paid to learn a skill,” says Cupertino’s Flanders. “The classroom training courses they take during their apprenticeship also qualify as college credits to get them even farther down their career path. In the same amount of time that students would complete an undergraduate degree, students choosing a trade complete their training with no debt, marketable skills, and credits toward an eventual degree.”

But to win them over, the industry must educate parents and students.

“A lot of people don’t talk about the opportunity cost: ‘This is what it costs to do this. This is what it costs to do that. And this is what you’ll get in return,’” DeLoach says. “I work with a lot of electricians and contractors. On average, most of them make a couple of hundred grand a year. None of them have educational debt.”

Career change

By 2029, the number of electrical jobs will grow 8%, or double the average for all occupations, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s another 62,200 openings to fill in addition to existing positions vacated due to people leaving the profession, such as retirement.

Although the industry is collectively working to attract people, contractors also need to develop their own strategies.

“They need to look at their current workforce and [ponder], ‘Four or six years from now, how many employees am I going to lose to retirement?’” says IEC Chesapeake’s Shmelzer. “They need to be forecasting and recognizing that they have to invest in their future workforce for four to six years from now.”

Besides working with local high schools, contractors also could target people in their 20s, 30s, and older, such as those stuck in dead-end jobs, unemployed due to the pandemic, or simply looking for a career change. The axiom that people don’t know what they don’t know applies here, too.

“Highlight the jobs that are available in that local area. A lot of people may not know they even exist,” says DeLoach, who also recommends reaching out to faith-based organizations. “You have to step outside of your industry.”

One of DeLoach’s students is a former security guard. A few years ago, a community newspaper in Philadelphia did a story about two Academy of Industrial Arts students. After his father showed it to him, the guard visited the school and was inspired.

“He never considered being an electrician even though his brother had been one for years,” DeLoach says. “He had a lot of drive. That’s what contractors need.”

Another Academy of Industrial Arts student is a woman who spent about 15 years as a restaurant manager until the pandemic. Her story highlights the importance of social media for building awareness.

“Somehow she wound up seeing one of my Facebook videos featuring other women,” DeLoach says. “She got a job offer from the second-largest solar installation company in Philadelphia because she had management skills and was on the path to learning about the electrical industry. They literally created a position for her.

“I have chefs, bus drivers, and transit mechanics. A lot of that comes from seeing the advertising I do. It’s a consistent effort and it’s diverse: all different ages, races, backgrounds. That makes a huge difference.”

SIDEBAR: In Short Supply

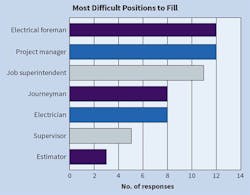

Worker shortages have consistently been a top concern in recent annual EC&M Top 50 Electrical Contractor surveys. The only thing that changes from year to year is the order of which positions are in the greatest demand. For example, electrical foreman, project manager, and job superintendent ranked highest in the 2020 survey results (see Figure below), while journeyman, electrician, and electrical foreman topped 2019’s ranking.

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Tim Kridel

Freelance Writer

Kridel is an independent analyst and freelance writer with experience in covering technology, telecommunications, and more. He can be reached at [email protected].