The Agile Construction Advantage

Celebrated among many building management gurus as the latest fad in construction, “lean” construction has become increasingly popular in recent years. Taking that approach a step further, the new concept of “agile” construction centers on a project's agility, allowing contractors to react to daily schedule changes and stay ahead of the curve while sticking to the same basic work plan.

Everyone knows change is the name of the game in the construction industry. As a result, some contractors, project managers, and foremen avoid planning because they know the schedule's going to change anyway. So why bother, right? Wrong. This type of reactionary approach actually has the opposite effect, stifling productivity and efficiency. Based on 15 years of research, the staff at MCA, Inc., Flint, Mich., asserts there is a statistically significant correlation between planning and productivity, which ultimately leads to profitability.

According to MCA, the agile response of contractors to changes on the jobsite can be managed by a simple “Three-Day Look Ahead” of labor, material, and tools. Let's see how to implement an agile construction approach step by step.

Job planning

You should categorize construction planning necessary to manage the project into four different areas:

-

Estimate hand-off to project management

-

Job layout and value engineering

-

Procurement planning

-

Job kickoffs (three-day look ahead — short interval scheduling)

To identify, track, and quantify the impact of planning on productivity and profitability, it's important to understand two key processes:

-

Job productivity assurance and control (JPAC)

-

Short-interval scheduling (SIS)

JPAC. Production in construction is defined by construction put-in-place and measured from an accounting perspective by earned revenues. Productivity is the effectiveness of production, measured by using the observed percent completion to evaluate labor productivity and report on whether resulting profits are above or below the expected earnings.

JPAC differs from the standard accounting approach for the measurement of job progress in that it measures day-to-day productivity versus a set construction budget goal, which typically focuses on measuring labor production. Accounting and enterprise resource planning (ERP) programs measure the job cost. Therefore, they measure production, not productivity. Production measurement will show the earned revenue, where productivity measurement will report on earned profits above or below the expected earnings.

SIS. Used to validate the JPAC productivity measurement as well as identify the root causes of special events on the job, SIS allows contractors to carry out its plans for productivity by bringing together the materials and labor needed to support a coordinated effort in managing all the aspects of the job plan. In SIS, the operator (electrician or foreman) is simply asked to schedule his/her work for the next three days. The schedule is then scored by the project manager on a daily basis, with deviations identified by cause.

Measuring productivity

By using only a few high-level company cost codes that define the activities performed, the productivity of the job can be tracked and projected from the labor's perspective. Measuring labor productivity with accounting methods allows hours to be moved from one cost code to another to hide the productivity variance. The contractor will pay for eight hours of work; however, he will never know which cost codes cost him how much. Productivity delays and their resulting impacts may not be recognized until the end of the project — when they are both most visible and most costly.

The initial JPAC plan by the project planning team involves segregating the job according to the type of work being performed. The cost codes should be only high-level “activity codes,” such as pipe, wire, fixtures, systems, fire alarms, etc., used consistently across projects on a company- or division-wide basis. Divisions doing different types of work may need to use a different set of cost codes, but each division should only have about 15 to 20. Of those, only seven to 10 different codes will generally be used on any one job.

Once the high-level cost codes are assigned with allocated hours, each cost code is then broken down into tasks by the project management team ( click here to see Fig. 1). The hours assigned to each task constitutes the job budget, which should reflect the way the technician or the operator will see the work performed. This budget may be calculated very differently than an estimate used to win the project.

MCA's research has repeatedly verified that the best foremen visualize the job by only the area that he or she is working on for a maximum of three days in advance, indicating the task breakdown in JPAC should be no bigger than three to five days. Therefore, the task breakdown should reflect the work in small, well-defined, measurable pieces, reflecting the way the electricians view job progress — tangible areas, such as one room, one wing, or one phase at a time.

On the job, the electrician reports the “observed percent complete” for each of the tasks he has worked on during the week. These completed percentages are compared with the high-level cost code labor hours submitted weekly to accounting. If the observed completion is outpacing the planned hours, the job is deemed to be ahead, and therefore more productive. The productivity is forecasted forward to predict the labor productivity at the end of the job, assuming the job proceeds at the current level of productivity in each cost code.

- Job layout

- Project plan

- Procurement plan

- Project schedule

- Productivity measurement

- Short interval scheduling

- Action to correct special causes

The SIS is a foreman's schedule, established and measured by the foreman on a short-term basis. First, a look ahead is established as the foreman determines which of the tasks contributing to the completion of the project his crew will be working on over the next few days.

For instance, ask the foreman to look ahead three days using the following questions:

-

What is your Plan A, B, and C for the next three days?

-

What do you need to do for each of these (material, manpower, tools, communication with other trades, etc.)?

-

What did you do yesterday? Did you do yesterday's Plan A, B, or C, or did you do something else?

-

If you did not do yesterday's Plan A, why not?

By evaluating the foreman's responses to these questions, a project manager can more accurately predict his material and manpower needs, track the project plan, and improve the bandwidth of communication between everyone involved.

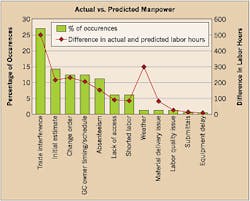

MCA's research has shown that the No. 1 cause of failure to comply with the short-term schedule is trade interference (Fig. 2). However, the most-heard complaint from the field is that the materials are not available — a result of working on Plan D instead of Plan A or B.

Correlation of planning and productivity

Current means of measuring production are primarily driven by accounting measurements. Even though these accounting measurements are necessary, they do not report productivity.

Using accounting measurements of production to stand in as measurements for productivity is not unlike driving with the rear-view-mirror only. By the time the data from operations in the field have been scored, reported, and produced, weeks and sometimes months have passed. This accounting approach significantly reduces the agility in the field and does not allow the contractor to respond immediately to the special causes occurring on the project.

The nucleus of jobsite productivity measurement is the run-chart: tracking the “how” and “what” of the productivity while indicating how the contractor should react to it. By using JPAC to indicate where and when productivity issues are occurring, and by scoring an SIS, the field supervision can look for underlying root causes of productivity changes on the job.

Figure 3 shows the direct relationship between the unplanned hours as measured during the scoring of the SIS and job productivity, tracked with JPAC, over the same time frame. When more hours are spent on any activity other than those scheduled for the day, job productivity declines. Conversely, when the job is worked as scheduled — or fewer hours are spent doing unscheduled or unanticipated work or even no work — the overall productivity on the job shows an increase.

In the end

According to MCA, agility, not leanness, is what construction jobsite management needs. In spite of schedule changes, the plan needs to proceed. Planning allows the contractor to use knowledge to minimize risks on both the company and project level in order to profitably complete the work on time and on budget.

By planning the progress and then allowing the operator to indicate the ongoing progress against the plan at regular, frequent intervals, the contractor can take action and make course corrections. The direct correlation between planning and productivity leaves the contractor no reason not to plan and execute — and goes a long way toward increased profitability.