Fire statistics in the United States are collected by means of a reporting system called the National Fire Incident Reporting System (NFIRS). This system is operated by the federal government, specifically the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA publishes some statistics from this database, but a more comprehensive analysis is provided by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). From this data, we can determine that approximately 20% of structure fires reported to fire departments (these are the only fires that are counted) are classified as electrical fires.

Defining an electrical fire

What exactly is an electrical fire? Some countries have such antiquated reporting systems that if a person overheats a pan of cooking oil on an electrical stove (and the burning oil ignites their kitchen), it’s reported as an “electrical fire.” Most readers realize that such a definition is inaccurate. But what is the best definition? Although our industry has not hashed this out, in my view we can use the following definition: “Electrical fire — a fire occurring due to a static electricity discharge or an electrical fault or failure.”

This definition recognizes that wiring or equipment must malfunction in some way for a fire to occur. It also recognizes that static electricity (which includes lightning) must be encompassed, but that “fault” or “failure” are not terms that are usefully applied to static electricity. This is because (apart from certain specialized equipment) static electricity discharges are not a normal feature of our environment.

Electrical fires are the No. 2 cause of structure fires, while the No. 1 cause is cooking, as noted in NFPA's "Home Structure Fires," written by Marty Ahrens and Radhika Maheshwari. NFPA claims that arson is the No. 4 cause but only accounts for 8% of total structure fires. However, research has shown, including a report presented by Dr. David Icove on “Project Arson: Uncovering the True Arson Rate in the United States” at the International Symposium on Fire Investigation in 2014, that with regard to arson, NFIRS statistics are suspect, and the true value is probably much higher. But the 20% or so fraction of electrical fires may actually also be higher. The problem is that while EEs or electrical inspectors are trained and qualified to understand electrical fires, fire department personnel generally are not. Thus, fires reported as “undetermined” are likely either electrical or arson, with the fire department unable to make a definitive finding.

Another problem with NFIRS is that the system does not have a single “bin” for electrical fires. There is a bin for electrical distribution and lighting equipment, but it only covers the electric power distribution system. Much of the remaining electrical fire cases fall under various categories of “equipment.” From such categorization, it’s difficult to determine what is an electrical cause and what isn’t.

Let’s take water heaters as a simple example of equipment. These plumbing fixtures are rarely abused or misused, but they do fail and cause fires. However, the statistics don’t consider that some water heaters are electric while others are gas-fueled. The latter may be associated with fire incidents, but they will not be electrical fires. Thus, the 20% value will not be directly found in the NFPA reports and requires some effort to make the best estimates and tally all contributing factors.

Top causes of electrical fires

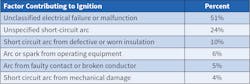

Although it’s useful to know what fraction of all fires is electrical, it is even more relevant to examine the causes of these electrical fires. Here, the national statistics are also not absolute. Table 1 shows the breakdown of fires as established by NFIRS. The lack of knowledge is evident in the dominance of “unclassified” and “unspecified.”

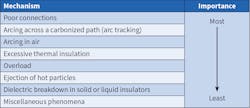

Given this unsatisfactory situation, the best recourse is to reflect on forensic experience. I have had a long career in fire safety science, with the last 25 years predominantly focused on forensic work. Table 2 shows rankings I produced based on my experience.

The top three mechanisms should be of major concern to all persons involved in electrical safety. The No. 1 mechanism is poor connections. Yet, NFIRS statistics do not recognize this category at all. It also does not recognize No. 2, which is arc tracking. Another important thing to note about this list is that there is no entry for “short circuits.” Clearly, short circuits occur and can be dangerous. Nevertheless, they do not comprise a single mechanism by which a fire can start. The mechanisms that might be involved in short-circuiting are many, but certainly arcing in air, ejection of hot particles, and dielectric breakdown of solid insulation will be important ones.

For a breakdown of mechanisms that is based on statistical study rather than forensic experience, let’s turn to a Canadian governmental agency that readers may not be acquainted with: the Electrical Safety Authority (ESA) of Ontario. This agency has a mission to study electrical accidents and injuries, including fires and electric shock incidents.

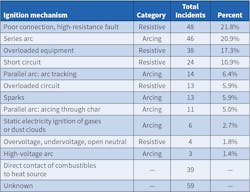

In 2008, this agency set out to find the mechanisms that led to electrical fires in Ontario. Their results, collected from the Electrical Safety Authority’s “Electrical Ignition Causes of Fires in Ontario from 2002 to 2007,” are shown in Table 3.

The percent values presented exclude the unknowns and direct contact of combustibles to a heat source (which are not electrical fires according to the prior definition). The outcome is not perfect, but it is more useful than the NFIRS output.

Poor connections are the No. 1 cause, which aligns with my experience in the United States. Since arc tracking and arcing through char are considered synonyms, both by myself and by NFPA, they should not be placed into separate categories. Short circuits, as stated, are not a unique physical mechanism. Also, overvoltage is not a failure mechanism; if it results in overload, then overload is the mechanism, while dielectric breakdown is another possibility. Thus, although the ESA scheme is not flawless, it is a major advance over what NFIRS has to offer in the United States.

The United States vs. Canada

In fairness to the U.S. situation, it is important to emphasize that the ESA statistics were compiled by EEs working at ESA and analyzing in detail electrical fire incidents. Such resources are not available to the fire departments that input their data into NFIRS. Overall, though, electrical fires in Ontario, Canada, are likely to be much more similar than dissimilar to those in the United States. Thus, the ESA findings should be helpful to safety specialists not only in Canada but also in the United States. Note that this study was a one-off effort so data for later years is unavailable.

Dr. Vyto Babrauskas is a forensic science specialist working in the areas of fire and explosion safety. He recently published the handbook, “Electrical Fires and Explosions,” in April 2021. He can be reached at [email protected].