Barely six months old, the words “coronavirus” and “COVID-19” are now forever etched into the index of world history. But a more familiar — and inherently more ominous — phrase, “the new normal,” has been resurrected as the world takes stock of how this pandemic has turned life upside down. Common activities taken for granted (such as airplane travel, sporting events, office meetings, concerts, shopping, and even a handshake) are shrouded in doubt as safety is reassessed amidst renewed awareness of mass vulnerability to viruses and microbes. The ultimate course of the coronavirus outbreak remains frustratingly unclear. But the enveloping crisis is a stark reminder of the ever-present threat of pandemics and the importance of devising measures to combat them.

COVID-19’s tentacles have reached deep into every corner of society and the economy, leaving little unscathed, including construction — one of the economy’s crucial pillars. When the coronavirus hit, many projects across the country were halted or even canceled as many states realized worker-dense construction sites were potential hotbeds for spreading the virus.

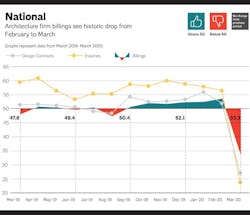

In a late-April survey, 68% of 850 member contractors polled by The Associated General Contractors of America (AGC) said they’d had a project halted or canceled by an owner since the pandemic’s onset, including projects both underway and planned. Reasons cited included the need to comply with nonessential activity restrictions, owner concern about COVID-19 danger, and altered project economics. Worry about construction’s longer-term prospects was heightened by another barometer: an alarming drop in the American Institute of Architects’ closely watched architecture billings index, which recorded its steepest-ever monthly decline in March (see Fig. 1). As of press time in early May, though, more states were taking steps to reopen their economies. That was raising prospects for restarts of construction projects that had been shuttered on either government or owners’ orders. In the handful of populous states that had classified most construction as nonessential, plans were being readied to allow it to resume, but under stricter rules designed to contain the spread or contraction of the virus.

Rocky Road

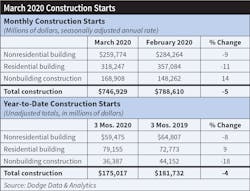

For construction contractors and subcontractors, including electrical contractors, the balance of 2020 (and likely beyond) provides anything but perfect vision for their businesses. The road ahead in an economy almost certain to plunge into a textbook recession — seemingly at the mercy of progress on corralling the coronavirus — is unclear. Some late-April government estimates had first-quarter GDP declining almost 5%. Dodge Data & Analytics estimated that the value of total construction starts fell 5% from February to March (see Fig. 2), suggesting construction could be a primary casualty in a prolonged slowdown. Another measure, though, showed construction holding its own. A May 1 Commerce Department report showed construction spending had rebounded. After falling 2.5% in February, it grew 0.9% in March.

With so much uncertainty, the stance being adopted by most contractors is “wait-and-see.” Some electrical contractors are already licking their wounds from the slowdown; others have been relatively unscathed. The concern is what lies ahead.

Most of the work underway at Sprig Electric Co., San Jose, Calif., had remained halted as of early May, the result of government-mandated construction stoppages. President Mark Mandarelli said he was not sure how much, if any, of that work would ultimately be postponed or canceled. Work that does resume, however, may have to be reassessed to account for the impact of any new work rules implemented to keep the coronavirus at bay.

“As jobs get going again, there may be some challenge to document, measure, and identify the impact on our work and our contracts of any changes coming from the Occupational Health and Safety Administration or general contractors,” he says.

Uncertainty about how job sites will operate and projects will get restarted concern Faith Technologies, Inc., Menasha, Wis., which had seen not only spotty construction project disruptions and service work-suspensions in the spring, but also a record number of new project proposals go out during a six-week period, countering any pessimism.

“If we can get this situation stabilized — and we have a good understanding of how we get back to work — I think we’re set up for a quick rebound,” says Tom Clark, chief experience officer for Faith Technologies.

The specter of a recession and its likely impact on construction concerns doesn’t paralyze Jim Bodrato, vice president of Pearl River, N.Y.-based USIS’s electrical division, which had a $60-million backlog at the start of the year. The division, which furloughed almost 500 electrical workers and saw most of its construction projects stopped but expects many to resume, is ready to pursue more maintenance, fit-out, and structured cabling work in conjunction with other USIS divisions should the construction economy sour. He is also convinced that a mild recession could even jump-start some projects whose developers were waiting for a downturn to secure better terms.

Working in a region that has seen comparatively less construction project closures, Encore Electric, Lakewood, Colo., was feeling its way through the crisis, hopeful it could escape relatively unscathed. President Willis Wiedel said the company’s 2020 backlog was intact and looked firm into 2021, but that an air of uncertainty prevails.

“Our work in data centers, hospitals, labs, and schools looks to be work that’s deemed essential, but that doesn’t mean we’re not working in a fragile environment,” he says.

Uneven Impact

Those are also the types of projects that could weather a construction downturn better than others. The pandemic’s boosting of remote work has clarified the need for a more robust digital infrastructure supported by more data center capacity, and the need for robust health care, warehousing, and possibly manufacturing infrastructure has come into sharper relief as well. On the flip side, demand for leisure, lodging, and commercial construction could be dramatically dented if long-term consumption patterns change.

David Chorley, president of Continental Electrical Construction, Chicago, sees demand for office buildings changing if a trend to more home-based work takes hold. “There could be a downsizing or changing of the structure of office spaces,” he says. “We don’t know how that looks moving forward.”

Chorley, noting that some industries had nearly “dried up” in a matter of weeks, sees some construction markets that have done well now at risk of a long struggle.

“There will be pockets where it will be hard to recover, such as hospitality, but others like mission-critical and even food processing that could see an uptick,” he says.

Mandarelli, whose firm has been involved in many large, extended campus development projects for Silicon Valley tech behemoths, says he’ll be watching with interest to see what impact the pandemic has on that market. “It’s still to be determined how this affects their strategies,” he says.

A lot is up in the air for contractors, maybe even after the air is cleared of the coronavirus. The course of business in progress, backlogged, and yet to be bid is one worry, but another might be how construction work itself could change. To address safety, contractors have had to deploy a raft of cumbersome new procedures for laborers to follow — from donning face masks and maintaining 6-foot separation to routine hand washing and regular temperature checks. As they’re rolled out, contractors may be in the early stages of evaluating the need for making such practices standard operating procedure.

“We may start to get back to normal in a few months, but I think social distancing and better hygiene is going be on everyone’s mind going forward,” says Vic Salerno, chief executive officer of O’Connell Electric Company, Inc., Victor, N.Y.

O’Connell was forging ahead with a high percentage of its work through the spring, much of it in the essential transmission and distribution sector, but workers in the field were having to follow guidelines on distancing and personal protective equipment (PPE) sanitation, causing work to slow on some projects. “It’s hurting; there’s no way it can’t be,” he says.

Much of the company’s office staff, including estimators and project managers, was working remotely and plans were in place to keep offices thinly staffed until authorities eased shelter-in-place restrictions. However, Salerno says the experience could open his mind to the concept of regularly conducting more work outside the office. “It might help productivity and might be safer with people on the road less,” he says.

Encore Electric emptied its offices of most staff in late February and began relying on Skype and other digital communications platforms to keep operations and still-active projects going, validating a deliberate two-year effort to get fully acquainted with those technologies, says Wiedel. They have been essential to activating a generic crisis management plan and convening a coronavirus task force created to manage through a period of restricted personal contact and have revealed a possible new way of regularly conducting business.

“We’ll likely go back to what we’re comfortable with at some point, but this has forced us into a place where we do have some level of comfort. We’re learning that we can work remotely,” he says.

Procedures now required on job sites to limit the introduction and spread of the coronavirus were not being implemented as seamlessly, Wiedel says, but could become standard operating procedure in the future. It may be too early to predict how many of the strict protocols now in place will survive the crisis, but Wiedel says it could make sense to keep many active. They may be needed across the industry to keep leery workers healthy and focused, and ensure construction doesn’t become a weak link in community efforts to keep future pandemics at bay. Distancing and face-masking, for instance, could prove hard to maintain, but routine hand- and tool-washing and sanitizing; less sharing of tools; regular worker temperature monitoring; and greater latitude for worker sick-day usage could become the norm.

“To say we’re never going to return to normal may actually be a good thing,” he says. “The best way to predict the future is to create it. There’s a chance that safety will now take on a whole new exciting role in the industry.”

Elevating Safety

Construction safety professionals likely see the coronavirus as a wake-up call for the industry. Contractors will have their hands full implementing and sustaining procedures to wall off job sites from the virus, but some predict the time invested in doing so will be used to assess new ways of working more safely that can survive the pandemic.

One expert, Rick Zellen, construction senior risk engineering consultant for insurer Zurich North America, expects many contractors — perhaps wagering that the duration of the crisis will be prolonged — to be proactive and creative in complying with detailed infection-control guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, AGC, and others. Possible tactics he cites include using third parties to conduct job-site-entrant temperature checks; detailed evaluation of personnel and precautions needed for specific tasks; instituting permitting procedures for high-risk tasks; moving to staggered work shifts and breaks; capping on-site hours for individual workers; and tracking all job-site activities more closely to aid in detailed “post-mortems” after the crisis abates.

The longer the crisis persists, the more likely it is that some practices become entrenched. Zellen says the new reality might include formulation and regular updating of detailed pandemic response plans; more accessible, ubiquitous, and higher-quality handwashing stations; more routine usage of higher-quality and more ergonomically designed PPE; more advanced, professionally staffed thermal scanning stations; the use of trade-specific plexiglass barriers to maintain distancing; and more thorough and routine disinfecting of job sites.

For now, Zellen says, contractors are feeling their way through the disruptions, but most are probably focusing on how to position themselves for a changed future.

“Our current way of working will likely prevail for a while, and it will force the industry to evaluate our readiness in the future,” he says. “The long-term impacts on contractors and how they perform their work are yet to be determined.”

Many electrical contracting companies and industry organizations have shared best practices for working on a job site during the pandemic. Here are just a few: “Guidelines for Construction Projects that Remain Operational” from NECA (https://bit.ly/3beoKNB) and Rosendin’s COVID-19 Response bulletin (https://bit.ly/2SNTkXV), which includes a list of potential “asks” for electrical contractors to pose to GCs/owners.

New Rules Possible

It’s a good bet that there will be more debate on the need to bolster infection controls in workplace safety rules issuing from government agencies like OSHA, says Brian Clarke, managing partner with G.E.W, LLC, a Battle Ground, Wash.-based construction safety and risk-management consultancy. If they do come, contractors would have to develop more administrative and engineering controls to address that, and site-specific plans might even be demanded of every subcontractor. In his view, the coronavirus has the potential to be a “game changer” on how construction projects are planned and executed.

“Just as lead and silica exposure have become workplace environment concerns addressed in safety rules, virus and pathogen control could be next,” says Clarke.

More attention to workplace hygiene would likely entail costs, but laborers would almost certainly welcome it. Don Finn, business manager for International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 134, in Chicago, says members who have chosen to work through the pandemic have felt progressively safer as contractors have taken measures to lower the risk of coming to work. And the more that some become a regular feature of job sites in the future, like regularly maintained portable restrooms and handwashing facilities, the better.

“No one knows where this goes, but we’ve always believed that the more attention we can give to cleanliness and hygiene on construction sites, the better off we’ll all be,” he says.

Nevertheless, many actions taken to protect workers and limit construction’s potential contribution to the spread of the coronavirus risk complicating work on job sites. Distancing mandates restrict worker mobility and change how some tasks are performed; fewer workers on site and smaller crews slows progress; more frequent handwashing, temperature checks, tool sanitizing, group safety talks, and site cleanings cut into productivity; and a new set of safety concerns and risk-avoidance practices could spawn inattention and lapses in monitoring other aspects of job safety.

Continental has found new distancing requirements to be the most disruptive.

“Wire pulling is one of the most affected tasks, and light fixture installations is another one,” says Chorley. “Basically, anything that’s set up as a two-man job has been more difficult to do. One of the things we’re looking at is the use of more lifts to work around the six-foot distancing rule.”

Distancing becomes more complex when projects are at stages where more contractors are on site and each might be at a different level of compliance or awareness, Chorley says. Manpower mobility is also compromised with new restrictions on the number of workers who can ride an elevator at one time.

In assessing how contractor clients are navigating the new requirements, Zellen says he has learned of electrical contractors now utilizing tools more in situations that require increased worker separation. The list includes tuggers to pull smaller gauge wire, circuit pullers that attach to cordless drills for pulling wire over longer distances, and electric wire strippers. Some have also modified the wire-pulling task, putting one worker at the reel, one at the feeder, and another at the head. Furthermore, some have installed additional rollers at the feed position to improve functionality.

Diverted Attention

Workarounds can open the door to other problems, however. With respect to worker safety, Clarke says contractors must guard against violating other rules when tasks that require more than one person are changed.

“Competing directives can put a job foreman in a bind,” he says. “There are rules designed to limit exposure to individuals carrying heavy objects, and if workers are now doing some things themselves, that’s a potential risk.”

Indeed, electrical contractor safety teams today are likely feeling more pressure than ever. With more attention diverted to a safety concern never encountered before, the risk of overlooking other dangers might be heightened, especially if fewer supervisors are present on job sites to keep crowding down.

“Other standard hazards may not get the attention needed because it’s been diverted to this new threat,” Clarke says.

One way electrical contractors might decide that construction needs to change to be better insulated from the next coronavirus is finding ways to permanently reduce the need for on-site workers. That could mean wider use of prefabrication, the technique of assembling electrical components in a manufacturing setting and their delivery and setup on the site once complete. It might also accelerate adoption of a broader building approach electrical contractors can participate in — modular construction — in which entire building components are delivered after full assembly and outfitting in a remote location.

The USIS electrical division uses a 60,000-square-foot prefab facility normally staffed by about 85 workers, but recently by less than half that during the slowdown. Bodrato sees the potential for using prefab more if there’s lingering or lasting interest in addressing job-site worker density.

“The advantage is being better organized and having workers operate in a clean, safe work area,” he says. “It’s more efficient, too. ”

A more controlled environment is the overarching benefit prefab offers Continental, says Chorley, giving workers more focus and space to complete assembly tasks. That might fit the bill for the current challenge and give the company a reason to ramp up its use to navigate new job-site constraints, especially on nontraditional installations.

“It’s probably another avenue we can go down to work through installation issues that have been impacted by COVID,” he says.

As the pandemic plays out with a resolution not yet in sight, electrical contractors will need to stay nimble to navigate new roads as they slowly resume operations and return to job sites. Ultimately, business as usual — a return to life before COVID-19 — could be in the cards. Equally likely is a scenario in which the virus ushers in permanent change. It may be wise to hope for the former but prepare for the latter.

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

Sidebar: Pandemic Effects on Electrical Service Work

Greater awareness of what is truly “essential” has been a byproduct of the coronavirus pandemic. Some construction has been halted because it hasn’t passed that test. But one area that may consistently meet that standard is electrical service and maintenance.

Much of that activity has continued through the coronavirus lockdown, even in commercial and industrial operations that may have scaled back operations to comply with shelter-in-place orders. Functional demands of even idled or reduced-duty manufacturing equipment, assembly lines, and building physical plant and infrastructure have meant continued employment for service and maintenance workers. But just as with electrical workers in construction settings, the pandemic has forced employers to rethink how they deploy electrical service and maintenance personnel so that workers are safe and necessary work gets completed. Similarly, it has likely sparked discussion about how service and maintenance activities might need to permanently change to reflect growing concern with infectious disease spread in the workplace.

High on the list of concerns specific to electrical maintenance is the safety of personal protective equipment (PPE), notably arc flash protective gear. Worries have been mounting during the pandemic that the common practice of having workers share is no longer advisable because it can be a vector for spreading infectious disease. Experts say the gear cannot be cleaned well enough to reliably kill viruses, leaving individually assigned PPE as the only safe solution for the future.

In a website blog post, Hugh Hoagland, managing partner with e-Hazard Management, a Louisville, Ky., electrical safety training company, said rubber insulating gloves are the only PPE component that can be easily sanitized between users. Even if all of it could be disinfected, he says most users are not set up to do that on a schedule that would allow safe sharing.

“I have yet to see a shared electrical PPE program that thoroughly cleans each item every time before it’s transferred to a new user,” he wrote. “The COVID-19 crisis is putting a spotlight on why this is a bad practice that needs to change — forever.”

Meanwhile, coronavirus fears have disrupted service and maintenance tasks in many settings. A safety engineer with a Massachusetts university said in mid-April that maintenance staffing had been halved in the interest of reducing worker density on site. That has meant some formerly team-structured tasks are now being performed by single workers, requiring more task analysis to maintain safety and quality control. Workers on the job were wearing face masks, regularly wiping down tools and limiting their sharing, and staying separated as much as possible.

“Scheduling is now key,” he says. “We’re doing more swing shifts and regular rotations, and if we have multiple trades involved we’re bringing them in at different times. So, a lot more communication is needed.”

On-site electrical training for maintenance workers has also been upended during the crisis. Randy Barnett, electrical codes and safety manager for NTT Training, Loveland, Colo., says the situation has helped accelerate deployment of online training. He has used it with clients in power plants and oil and gas settings in the spring and accomplished a first-ever switchgear de-energizing instruction with one using streaming video.

Digital technologies could come into greater play in electrical maintenance if one of the byproducts of the pandemic is the need to staff more lightly. Brian Clarke, managing partner with G.E.W., LLC, a construction risk manager in Battle Ground, Wash., says more companies could ramp up the use of remote monitoring.

“There could be more emphasis on preventive maintenance, maybe more troubleshooting using live video,” he says. “That could impact maintenance and repair schedules and maybe require fewer people.”