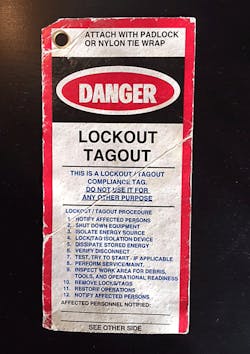

In the workplace safety arena, few practices have achieved as much buy-in and reverence as lockout/tagout (LOTO). With many service and maintenance worker injuries and fatalities linked to encounters with energized electrical components, machinery and equipment, manual procedures that produce and ensure de-energization warrant and typically get constant attention.

But for all the certainty it produces in so many situations, LOTO has been getting pushback from some quarters. Though its value is unassailable as an element of hazardous energy control procedures in electrical distribution systems operations and maintenance scenarios, the tactic has been getting more scrutiny in applications involving production equipment and machinery. In those, steady advances in engineered, built-in control systems that may provide greater task performance and operational flexibility while also shielding workers from harm present companies with what many experts say are viable, so-called “alternative methods” to traditional LOTO. And the ranks of companies acquiring that equipment and using such methods have been steadily growing.

An equipment/department lock secures an electrical panel.

(Photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.)

There is, however, one potentially formidable roadblock to continued adoption: The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA). OSHA, through its 29 CFR 1901.147 general industry control of hazardous energy standard, generally requires equipment and machinery to be locked out/tagged out prior to maintenance, repair, or troubleshooting work. In some cases where companies have sidestepped that rule and relied instead on alternatives, OSHA has cited them for violations, sometimes triggering administrative review and court challenges that have resulted in both overturned and upheld citations.

Nevertheless, OSHA’s rigid stance has produced mounting concern in some industry circles, and it’s been heightened by the agency’s expressed interest in clarifying the standard’s language and intent.

In October 2016, it proposed a wording change designed to effectively prevent companies from misinterpreting the rule and avoiding LOTO. Referencing various cases where employers were cited for allowing workers to rely on machine-integrated alternative methods they thought would alert and protect them from unexpected startup, OSHA announced its intent to revise its regulation by excising the term “unexpected.” With that change, OSHA argued, it would be harder for companies to assert that LOTO alternatives produced working environments in which startup or energization could be fully expected and thereby not subject to the OSHA rule.

In proposing the change, OSHA noted the rule’s wording; that the lockout/tagout mandate covers maintenance and servicing operations “in which the unexpected energization or startup of the machines or equipment, or the release of stored energy, could cause injury to employees.” LOTO, it argued, protects workers by ensuring full de-energization before work is performed and re-energization only after work is completed.

The electrical panel lock above includes a hazardous voltage warning.

(Photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.)

It says, LOTO is the first, and perhaps only acceptable and permissible, line of defense, rendering alternatives generally out of bounds. The proposal noted that the term “unexpected energization” was intended to mean “any re-energization or startup that occurs before the servicing employee removes the LOTO device from the energy isolation device or equivalent energy control mechanism.” Deleting “unexpected,” OSHA said, would “make clear that the lockout/tagout standard covers all equipment servicing activities in which there are energization, startup or stored energy hazards.”

Voicing Opposition

The proposed change, incorporated into the federal government’s broad Standards Improvement Project-Phase IV initiative, drew scores of responses through January 2017, most of it lodging opposition. Bruce Main, an engineer and safety professional who has helped shape guidelines on hazardous energy control and LOTO and has monitored the long debate, says only a handful of the roughly 140 comments submitted backed the idea. Most respondents, says the president of Design Safety Engineering, Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich., saw it as further proof that OSHA is out of step with technological changes and thought it would set back industry efforts to continue deploying safe, reliable, and efficient LOTO alternatives when applicable.

An electrical plug fitted with a lockout/tagout (LOTO) cover.

(Photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.)

“The trend is toward looking to use technology to improve productivity and safety, and to perform tasks like cleaning or clearing equipment jams without having to perform traditional lockout/tagout,” and that is one of the pillars of the opposition that was expressed, says Main, a co-author of the 2016 book, The Battle for the Control of Hazardous Energy, which examines the many conflicts between the ANSI Z244.1 industry hazardous energy control standard and enforceable OSHA rules.

One of the groups commenting, the Chamber of Commerce of the United States, said the OSHA proposal ignored progress that’s been made in developing and extensively deploying proven technology, a representative response.

A control panel is locked out and tagged with a warning that removal is restricted to a named individual (photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.).

“It would ban every device and method that may now be used to negate the unexpectedness of a startup, including highly reliable modern control circuitry,” the Chamber’s letter stated. “Lockout is an expensive, inflexible and time-consuming administrative control, dependent on employee adherence to it to be effective, whereas modern technology-based systems are engineering controls not dependent on employee actions to be effective.”

Since proposing the rewording and receiving comments, OSHA has been quiet about next steps. It’s unclear whether the agency has backed down due to the negative feedback, regulatory priorities of the Trump administration, or for other reasons. After the comment period ended, OSHA did serve notice that it was considering a formal request for information (RFI) regarding the “strengths and limitations” and “potential hazards to workers” of computer-based hazardous energy controls that conflict with its LOTO standard. It added that a “stakeholder meeting and open public docket to explore the issue,” might be warranted.

A lockout point on a control panel carries an arc flash and shock hazard warning.

(Photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.)

In mid-April, an OSHA spokesperson informed EC&M she couldn’t provide any update on the status of the agency’s proposal. “We are awaiting publication of the Standards Improvement Project rule in the Federal Register,” after which time more information might be available, she said.

The fact that OSHA has been mum for two years could mean the proposal is dead, at least for now. Main thinks that’s the case. “I don’t think there’s an active effort from OSHA at this point. They’ve not had or scheduled any hearings that would be required.”

Others who have followed the debate concur. Alan Metelsky, chief controls engineer, new product development for The Gleason Works, Rochester, N.Y., a production systems manufacturer, and a member of the committee that wrote the current version of the ANSI Z244.1 standard in 2016, senses that “nothing is coming down the pike from OSHA on this.” Edward Grund, Main’s co-author on the 2016 book and president of Grund Consulting, Inc., Chicago, says the “storm of comments” OSHA got to its “backdoor run at changing the wording” has probably caused it to retreat.

Here, an in-line valve is outfitted with a lockout mechanism (photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.).

But even if OSHA has abandoned the wording change push, companies using or contemplating LOTO alternatives remain in a state of what might be called “regulatory purgatory.” Using alternative methods puts companies at risk of citation for violating 29 CFR 1901.147, even though OSHA’s enforcement of the rule has been scattershot, and the agency has selectively approved official “variance” requests for LOTO alternative procedures. And it still leaves companies in a quandary over how to balance compliance with OSHA’s regulatory requirement and adherence to modern industry standards laid out in ANSI Z244.1 that endorse and offer detailed guidance on using alternatives.

Challenging OSHA

OSHA’s track record in having its citations for LOTO violations involving alternative methods challenged is part of the concern.

In some cases, the government’s Occupational Safety and Health Review Commission (OSHRC) has turned down appeals of citations. A 2007 challenge by Burkes Mechanical, Inc., was rejected because OSHRC said the claim that workers servicing equipment that hadn’t been locked out knew it was moving did not insulate them from the LOTO requirement. Similarly, OSHRC in 2013 upheld the agency’s citation of Otis Elevator for allowing a worker to unjam an elevator’s stuck gate assembly without proper energy controls in place. Energization would be unexpected because, despite knowing the gate would start to move when unjammed, the exact timing of the unjamming couldn’t be known.

This image shows an electrical disconnect on a heavy-duty safety switch capable of being locked out (photo courtesy of Design Safety Engineering, Inc.).

In other cases, OSHA citations have been overturned. In arguably the most prominent case, the one that prompted the agency to seek the wording change, OSHRC, and subsequently a federal appeals court, backed GMC Delco’s late 1990s claim that a multi-step start-up procedure it employed for servicing a machine excused it from the LOTO requirement. The procedure, involving eight to 12 steps, including time delay, an emergency stop, and audible warnings, meant startup would not be unexpected, according to the rulings. The court noted that the rule’s “plain language unambiguously renders the rule inapplicable where an employee is alerted or warned that the machine being serviced is about to activate.”

That defeat rallied OSHA’s LOTO hard-liners and spurred them to try to head off any future challenges that might invoke the same defense. Warning devices, it said, were considered when the regulation was crafted, but they were deemed “impractical and dangerous” because

they burden workers with the demand to be cognizant and aware when they should be entitled to work in conditions expressly made safe. “OSHA intended to protect employees effectively from all forms of hazardous energy by isolating machines from their energy sources during servicing and/or maintenance,” it said.

If it’s business as usual with respect to LOTO enforcement at OSHA, companies may continue to be unsure about what course to follow with using LOTO alternatives. The agency continues to write up LOTO violations of all sorts at a steady clip, so employers know that OSHA inspectors have that on their radar. LOTO is among the most cited OSHA violations every year; it ranked fifth in number of citations on the agency’s list of top 10 violations in 2018 and is consistently in the top five every year.

Citations could conceivably skyrocket if OSHA were to end up making the wording change that would effectively take rule interpretation and review out of play, one of the factors that encourages some companies to employ recognized and vetted LOTO alternatives and risk an OSHA enforcement action.

Those that do usually look to ANSI Z244.1, the industry consensus standard whose approach to LOTO is far less rigid and has been routinely revised over time to reflect the latest technology that is often substituted for LOTO.

But for those companies, the only thing worse than OSHA tightening up its standard might be OSHA conducting business as usual with respect to LOTO enforcement. Uneven enforcement, challenges to OSHA rulings, technology advancements, and conflicts with competing standards has employers operating under a cloud of potentially paralyzing uncertainty, complicating efforts to craft long-term strategies for revising, standardizing, and modernizing approaches to hazardous energy control.

The Case for Alternatives

Companies are increasingly drawn to LOTO alternatives because they offer a streamlined approach to a multi-layered challenge. De-energizing machinery and equipment can be time-consuming, especially if it’s a practice rigidly applied in advance of work that could span

maintenance, cleaning, clearing, calibration, inspection, or even observation. And with modern equipment designs that incorporate robotics, more such work must be done with power on. In today’s fast-paced, uptime-critical production settings, an extreme LOTO policy can be time-consuming, potentially costly, and ripe for violation by time-pressed workers, so interest in alternatives that don’t compromise safety is high.

Mike Taubitz, senior advisor at FDR Safety, a Franklin, Tenn., safety consultancy, says a more nuanced understanding of hazardous energy control is needed, especially as LOTO alternatives that use technology like control reliable circuitry become more capable.

“The biggest issue in this debate is not how or what to lockout, but rather when,” he says, explaining that it’s difficult for employers to ensure LOTO will be done consistently and correctly. “There can be compliance risk by not doing it, but if it’s blindly mandated that everything is locked out it will be difficult for workers to follow that policy. If OSHA were to succeed with the wording change, you’d shut down production.”

LOTO alternatives have come to the fore not just because they’re comparative time savers, but also because lockout/tagout as practiced can be cumbersome, avoided, improperly and inconsistently performed, and risky. Paring down the range of scenarios to where it’s essential — performing electrical system maintenance work, for example — could boost compliance overall and make for a safer workplace.

De-energizing has grown more complex and involved, often requiring trained and qualified workers in personal protective equipment, says Metelsky, and the more frequently workers do that and perform complex LOTO tasks, the more risk they face.

“Workers cleaning up machinery or changing tooling, and being told they should operate a disconnect, if they do it often enough the risk goes up,” he says. “You don’t want to be exposing workers to the hazards of doing that 10 times a day.”

In their book, Main and Grund reference the arc flash danger present when conforming to OSHA requirements on cycling an energy isolating device. Accessing electrical panels to operate the disconnect requires arc flash personal protective equipment (PPE) and prevention procedures. Additionally, the risk can compound over time.

“These devices are often not designed or intended for frequent ON/OFF cycling that may occur during frequent servicing tasks such as clearing jams… (and) the additional wear and tear greatly increases the potential for arc flash or electrical failure,” the authors write.

Nevertheless, many employers will continue to feel pressure to perform those tasks and others that conform to a strict reading of OSHA regulations. Others though, guided by the alternative method-friendly ANSI standard for selected tasks, will continue to look for safe and efficient ways of protecting workers that don’t involve comprehensive LOTO. Those in the latter camp, however, should carefully design and document procedures with worker safety paramount and be ready to defend their actions to OSHA inspectors and face possible citation.

“The trick is to make sure you have good system controls,” says Main, explaining that the ANSI standard only allows alternatives in circumstances and configurations that ensure worker safety to an LOTO-equivalent level. “Many of these procedures work in theory, but if you have electronic stop circuitry that’s not up to Category 3 standards, for instance, you could have failures in the system and be at risk and not know it.”

And that uncertainty is seemingly what worries OSHA and may partly be driving efforts to revise C29 CFR 1901.147. Some, however, believe that push was the result of OSHA’s stubbornness and reluctance to develop over a period of many years a comprehensive understanding of LOTO alternatives that would give its inspectors the ability to fairly judge their use. What’s needed now, some say, is an agency commitment to modernize its interpretation of hazardous energy control procedures, and to begin to work with industry and incorporate ANSI consensus standards into its regulations and enforcement activities.

“They need to create a standard that fits 2020,” says Grund. “Employers are more willing, by necessity, to use systems technology and proprietary industry-oriented solutions that OSHA may not even be aware of. OSHA has specification standards rather than the performance standards that can give employers the flexibility they need. They’re in the way of allowing them to move forward.”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lees Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].