When OSHA published its new confined spaces rule in the Federal Register on May 4, 2015, it shook the construction industry by initiating strict requirements to better protect workers performing tasks in confined spaces, such as manholes, crawl spaces, and tanks, from asphyxiation and other potentially fatal hazards. After being issued in May 2015, it became effective on August 3, 2015. As of March 8, 2016, however, all temporary enforcement of OSHA’s new Construction Confined Space standard, Subpart AA, has lapsed. The last piece to fall into place is the direction that “state plan” states will take with adopting the federal rule as-is or promulgating more strict language (see OSHA-Approved State Plans).

Part of OSHA’s reasoning for the new standard is described in a study of construction industry fatalities from 1992 to 2000. OSHA estimates that the new standard will prevent five fatalities and more than 750 serious injuries every year — this is approximately 96% of injuries and fatalities relevant to confined space in the construction industry. With an average cost of $62,000 per prevented injury (and a value of $8.7 million per prevented fatality), OSHA estimates a benefit of $93.6 million annually.

Relating specifically to electrical contractors and other wiring installation contractors, OSHA has identified more than 79,000 total firms nationwide that will be impacted by the final rule. This number covers more than 825,000 employees working on an estimated 2,680 projects with confined spaces each year. In addition, work conducted by residential contractors engaged in remodeling work like electrical systems in multi-family housing is considered construction activity, and these employers must follow Subpart AA as well.

Quick refresher

As employers and workers in industries impacted by OSHA’s new Subpart AA, it is important to read not only the text of the standard but also to familiarize yourself with the language included in the preamble. The full text of Subpart AA is about 27 pages. The preamble is much more extensive, and includes OSHA’s case for the new standard as well as many specific examples of how to apply the rule to your workplace. In the preamble, several requests for exemption were described, many of which are applicable to electrical work and discussed below.

In the case of home construction, for example, the preamble describes the hazardous atmospheres and engulfment hazards that can be encountered by those working in attics, crawl spaces, basements, cabinets, and other areas of a home building, including electrical hazards. Fatalities due to electrical hazards were a general cause of fatalities in crawl spaces under homes and deemed an exemption inappropriate for these spaces — as it would not be consistent with the purpose of the standard.

Another exemption requested was related to Subpart V – Electric Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution; Electrical Protective Equipment. Commenters were looking for consistency between the general industry and construction rules related to confined spaces, noting a potential gap in regulation if work related to Subpart V was exempted from the construction confined space standard. OSHA disagreed with an exemption, noting that Permit-Required Confined Spaces 29 CFR 1910.146 does not apply to construction activities. The term “routine” is key here: Routine confined space entry for construction work would be less common.

The standard indicates that electrical hazards are categorized as a physical hazard, and such hazards should be identified and eliminated. Reclassification procedures are described in which an employer may reclassify a permit-required confined space (PRCS) as a non-permit space if no “actual or potential atmospheric hazards are present, and the employer eliminates all other hazards in the space.” OSHA went on to state in the preamble that this will apply mostly to spaces where the employer eliminated or isolated the physical hazards. The provision does not dictate how hazards are to be controlled, but it does state that the employer should still conduct a thorough hazard assessment of the confined space that includes electricity associated with the process, exposed and energized electrical conduits, and any other recognized hazards covered in OSHA construction standards or the general duty clause.

The elimination of a hazard will not result in reclassification of the space in all cases. A competent person must conduct a full reevaluation of the permit space before reclassification. The preamble cited an example of a space with a single electrical hazard that can be locked out. If the space has no atmospheric hazard — and an employee must enter the space for the electrical hazard to be locked out — then the lockout process may need to be conducted under the full PRCS requirements. Once lockout is completed and a competent person verifies that it is properly isolated — and there are no other hazards in the space — the employer can reclassify the space as a non-permit space.

Entry permits are required to be documented with the date and authorized duration of the planned entry. Per the preamble, the “date” refers to the day that the authorized entrants are permitted to enter the PRCS. The duration does not need to be described in terms of time and can be defined by scope of the project. An example of the preamble is “upgrading equipment in an electrical vault.” This ensures employees working in the PRCS understand the period during which conditions must meet what is specified in the entry permit. It is also an attempt to put a reasonable limit on permit durations.

Electrical cases in point

One fatality related to electrical work highlighted in the preamble was an incident that occurred in 2000 at a water desalination facility site. Two employees of an electrical contractor died while working in a 26-foot-deep sump manhole. Both employees were found unconscious at the bottom of the manhole by an employee of the general contractor. An outside rescue service from the local fire department responded to the site and discovered that oxygen in the space was only at 8%. Post-incident investigation found that oxygen levels were as low as 2% in some areas with elevated levels of nitrogen and carbon dioxide. The investigation found that biological activity surrounding soil that entered perforated piping may have consumed the available oxygen and generated the high levels of nitrogen and carbon dioxide.

The preamble also included several fatality incident descriptions involving residential workers electrocuted in crawlspaces of homes. Each description includes controls, many of which relate back to communication and training that could have prevented the fatalities. OSHA deemed the majority of these fatalities related to construction in confined spaces were entirely preventable. In most cases, three to five safety controls were not in place, which could have prevented the fatality.

Communication is key

Subpart AA goes into extensive detail to ensure that communication is conducted before, during, and after each permit-space entry. The communication is led by the controlling contractor in coordination with the host employer and entry employers. If your company works in a controlling contractor capacity, a communication plan should be developed pursuant to 1926.1203(h)(2).

Before work in a permit space is conducted, the location of the permit space, its hazards, and any precautions used in the past should be discussed. The controlling contractor is required to obtain the host employer’s information about the permit space, its hazards, and previous entry operations. This information must then be provided to any entity that will enter the permit space. In addition, information should be shared with those not entering the permit space if their work activities could “foreseeably” result in a hazard in the permit space. As it is the controlling contractor’s responsibility to provide this information, it is the responsibility of the entry employer to obtain the information. Entry options should be coordinated when more than one entry employer is sending personnel into a permit space at the same time and when activities could “foreseeably” result in a hazard in the permit space.

Communication is required at the end of the entry operations as well. The controlling contractor again takes the lead to debrief each entry employer of the permit space program followed and any hazards that were encountered or created during entry operations. In turn, the entry employer must give the controlling contractor information about entry program and hazards they encountered or created in the space. The controlling contractor then passes all of this information back to the host employer, who would then provide the information again in a similar entry situation.

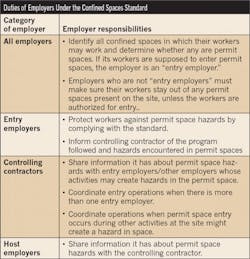

When a controlling contractor is not present at the job site, the host employer or other employer who arranges to have personnel from another employer perform work fulfills this role. It is important to understand contractual relationships at work sites where permit-space entry work will be conducted. These relationships will tell you which entity fulfills each role (or multiple roles): host employer, controlling contractor, and entry employer (Table).

Five key differences

Since the general industry standard for confined space has been around for quite some time, it is beneficial to look at Subpart AA by comparing it to 1910.146. There are five key differences between the existing general industry standard and the new construction standard.

1. The detailed requirements for coordination and communication between multiple employers at the worksite (as discussed more in-depth earlier in this article). This communication is required because construction sites are truly different than general industry sites. They are often a tangled web that can only be sorted by closely reading the contract and specifications.

2. The role of the competent person in evaluating confined spaces. Each employer with employees entering a permit space to perform evaluation or work must designate a competent person.

3. Continuous atmospheric monitoring is now required to be done whenever possible. In short, you must continuously monitor the confined space unless your employer can prove the technology does not exist yet to do so.

4. In addition to the continuous monitoring of atmospheric hazards, engulfment hazards must also be monitored at all times during permit-space entry. This is the part of the new standard that is anticipated to have the single greatest impact on contractors, especially those conducting work inside wastewater and water treatment facilities. You simply cannot isolate all hazards in most of those settings. Complying with this part of the standard will require extensive planning.

5. The employer can now suspend a permit instead of canceling it. This is a practical approach to the permitting system, which was often construed as confusing and extra work.

The bottom line

As an employer with personnel entering confined spaces to perform construction work, you have a few basic responsibilities:

• Develop and implement a written program that complies with Subpart AA. This program must be made available to employees before and during entry operations.

• Designate a competent person who should be capable of identifying confined spaces, their hazards, and applicable controls.

• Identify permit spaces that workers may work inside. This includes spaces at your own facility, if applicable, as well as host employer sites. Each project’s scope of work should be evaluated for confined space hazards (whether permit-required or not). These spaces should be identified physically as well with a sign or other visual indication and verbal information given to other employers at the work site.

• Implement measures to prevent unauthorized entry by workers who do not need to be in the confined space to perform work. Again, this can be achieved through physical and visual means as well as verbal.

• Identify and evaluate the hazards of all permit spaces prior to entry. This is the basis for the permit system — the documented thought process of safe permit-space entry.

Employers are required to provide equipment to employees for safe permit-space entry. This equipment should be maintained, and employees should be trained in its safe use and limitations. This equipment includes testing and monitoring devices, ventilation equipment, communications equipment, personal protective equipment (which may require additional written programs and training), lighting equipment, barriers, equipment for safe access and egress, rescue and emergency equipment, and any other equipment necessary for safe entry, exit, and rescue.

As with all written safety programs, review the policy frequently (at least annually and when operations or personnel change), and keep up with the latest regulatory updates.

Ferri is the CEO of The Ferri Group LLC in Minneapolis. She can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR 1: OSHA-Approved State Plans

If you live in one of the “state-plan” states listed below, follow your state’s current rule until they update or replace it. These states were called out in OSHA’s Preamble to Subpart AA as having a rule in place that is similar to the new rule:

- Alaska

- California

- Kentucky

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Minnesota

- Virginia

- Washington

This leaves out states that do not have a similar rule already in place or incorporate federal OSHA rules in full. State-plan states have six months from promulgation of a federal rule to meet or exceed it. The six-month period ended in February 2016. According to the Law Atlas State Occupational Safety and Health Standards map, five states currently have standards that address the topic of engulfment hazards specific to confined spaces (Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Virginia, and Washington). This is a good indicator of which states meet Subpart AA. The remaining 21 state-plan states must meet or exceed Subpart AA, and promulgation is forthcoming.

Twenty-six states, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands have OSHA-approved state plans. Twenty-two state plans (21 states and one U.S. territory) cover both private and state and local government workplaces. The remaining six state plans (five states and one U.S. territory) cover state and local government workers only.

Source: OSHA (https://www.osha.gov/dcsp/osp/)

SIDEBAR 2: Vocabulary Brush Up

Early warning system: This is a method used to alert authorized entrants and attendants that an engulfment hazard may be developing. This could be an alarm activated by remote sensors, a person designated to lookout that has equipment for immediate communication with the affected personnel, or other system.

Entry rescue: A rescue service that enters a permit space to rescue one or more employees. Such services must have access to a representative space to conduct drills at least annually. This representative space must have the same or similar access and internal configuration as the permit space to be entered and should be provided whenever the actual permit space cannot be entered to perform a drill.

Immediately dangerous to life or health (IDLH): Subpart AA includes substances that produce “immediate transient effects,” which means the effects to a person may pass without medical attention, followed by sudden, possibly fatal collapse 12 to 72 hours after exposure. The victim may have felt normal after recovery from the transient effects until the later collapse. It is important to understand which chemical and substance hazards exist in a permit space to know if immediate transient effects could be experienced.