Around the globe, offshore wind turbines are producing clean, green energy. In 2016, America’s first offshore wind farm began operating. Today, projects are underway or in the planning stages nationwide.

“The U.S. offshore wind market is set to take off, thanks to research and technological advancements, cost reductions, and supportive federal goals and state procurement mandates,” says Jocelyn Brown-Saracino, offshore wind lead at the Department of Energy (DOE).

Offshore wind has unique challenges compared to land-based wind, due to the need to install and operate in the harsh marine environment and less-established supply chains. Despite these challenges, progress is being made to increase the speed and scale of United States offshore wind development, she says.

The amount of capacity in the U.S. offshore wind energy development pipeline increased by 14% from 2020 to 2021 to 40,083MW, and the market is continuing to expand. The DOE, in partnership with the Departments of Interior, Commerce, and Transportation, announced a goal to deploy 30 GW of offshore wind by 2030.

“Meeting this goal would unlock a pathway to deploy 110 GW or more of offshore wind by 2050, generate electricity to power 10 million American homes, and cut 78 million metric tons of carbon dioxide emissions,” Brown-Saracino says. “Offshore wind has the potential to provide substantial amounts of clean power to meet America’s sustainable clean energy future.”

The DOE stated that the Biden-Harris administration has made offshore wind a priority. Case in point: It set a goal of 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2035 and a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. While much of the United States’ clean energy deployment in the near term will be land-based wind and solar, these transitions will require a diverse portfolio of renewable energy sources, Brown-Saracino says.

“Offshore wind power plants can be sited near coastal population centers with high electricity demand and can be an attractive option in coastal areas that have transmission constraints on land or limited land available for new utility-scale wind or solar power plants,” she says.

Driving growth

Two key pieces of legislation — the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) — may have a further impact on the growth of this market. According to the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA), the IIJA is providing grants to ports, some of which are being developed to support offshore wind.

Specifically, the IIJA included $100 million for wind energy, which includes research on onshore, offshore, and distributed wind energy systems, advanced manufacturing, grid integration, and wind system recycling. It also has $2.5 billion set aside for the Transmission Facilitation Program, which will establish a revolving loan fund to facilitate the construction of new or replacement transmission lines. The $20 million for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration will deliver resources for offshore wind assessment related to protected resources and help with permitting and consultations.

“The IIJA included several important provisions for offshore wind while also directing funds to make the grid more resilient and better equipped to handle new clean energy capacity,” Brown-Saracino says.

The IRA includes long-term extensions of critical tax incentives supporting the development of all three wind applications — land-based, offshore, and distributed. In addition, it supports new financing programs to advance the construction of high-voltage transmission lines and overcome the siting challenges of new transmission projects, which will be important for both land-based and offshore wind.

“These credits provide long-term policy certainty to the wind industry and to investors that will help accelerate deployment and jump-start development of a sustainable domestic manufacturing supply chain,” Brown-Saracino says.

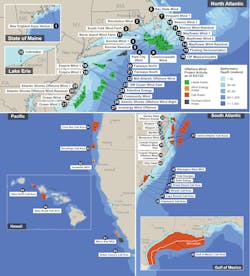

Leasing areas and advancing technology

“These new lease areas will substantially increase the number of offshore wind energy sites in the United States and provide regional diversification beyond the north and mid-Atlantic,” Brown-Saracino says. “It will also provide technology diversification.”

Currently, two-thirds of the nation’s offshore wind resource (including the entirety of the resource off the West Coast as well as the Gulf of Maine) have waters too deep for traditional fixed-bottom foundations. Instead, they will use floating offshore wind.

“We are in the midst of a really exciting moment for offshore wind currently,” Brown-Saracino says. “That’s true for fixed bottom offshore wind — the kind we’ve seen deployed widely commercially to date, where the turbine is attached to the sea floor typically through a monopile or jacketed foundation structure. But that’s also true for floating offshore wind — technology that’s capable of accessing wind resources deeper than 60 m, which is mounted on a floating foundation or sub-structure.”

Currently, the DOE is working to produce several future technological advancements for offshore wind. Some of these are blades and other turbine components; foundations (including floating platforms); increased turbine sizes to produce energy at lower costs; advanced full-system and array optimization to reduce weight and increase energy production; and support for offshore wind transmission needs.

The dominant trend in offshore wind turbines is the industry’s continued push for increased generating capacity to lower project costs, Brown-Saracino says. The average offshore wind turbine capacity installed in 2021 was 7.4MW, slightly down from 7.6MW in 2020, but still significantly higher than 3.3MW in 2011. All three major European manufacturers of offshore wind turbines are working on developing 15MW-class wind turbines with rotor diameters spanning up to 236 m (compared to 158-m-average rotor diameters in 2021), with plans for commercial production between 2022 and 2024.

Offshore wind turbine ratings have grown substantially over the last decade, doubling in megawatts, according to NYSERDA. In turn, this increases energy output and reduces the number of turbine positions in the ocean and the per-megawatt cost of projects. Looking to the future, the next era of floating offshore wind will likely be even further from the shore, making an offshore grid more important, notes NYSERDA. In fact, NYSERDA’s latest offshore wind solicitation introduces a first-of-its-kind, meshed-ready offshore transmission configuration, which will facilitate offshore wind projects’ transition to a future system that can grow over time and provide greater reliability and flexibility.

Generating clean energy in the Northeast

Currently, New York has five offshore wind projects in active development. The state has the largest offshore wind pipeline in the nation totaling more than 4,300MW. This represents nearly 50% of the capacity needed to meet the state’s offshore wind goal of 9,000MW by 2035.

According to NYSERDA, 2022 has been a banner year for offshore wind development in New York. In January, NYSERDA finalized contracts with Equinor and BP for the Empire Wind 2 and Beacon Wind Projects. A month later, South Fork Wind, the state’s first offshore wind project, broke ground on Long Island. Once it comes online in 2023, it will be one of the first commercial wind farms in the nation.

Last year, the first two commercial projects in federal waters started construction: Vineyard Wind 1 and South Fork Wind Farm. Vineyard Wind 1 is being constructed 15 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, Mass., and will produce 800MW of clean energy, enough to power more than 400,000 homes. The South Fork Wind Farm is under construction 35 miles east of Montauk Point, N.Y., and will produce 132MW — enough to power 70,000 homes.

Training workers

As the United States continues to develop and construct new offshore wind farms, it will unlock a pathway to support 77,000 jobs (44,000 in the offshore wind industry and 33,000 in surrounding communities).

Workers from oil and gas and other industries, including electrical contractors, engineers, and suppliers, will be able to transition into the offshore wind energy workforce on a regional and national basis. To provide support, DOE is currently assessing existing educational and training programs for offshore wind, outlining anticipated training needs and identifying potential gaps to meeting workforce needs.

In New York, NYSERDA’s $20-million Offshore Wind Training Institute has invested in two programs at Hudson Valley and LaGuardia Community Colleges to help establish a skilled workforce to support the emerging national offshore wind industry.

“Offshore wind is both a critical economic driver and a tremendous source of clean power that will help transform how we live, work, and do business,” NYSERDA stated.

Note: For more information about the state of U.S. offshore wind, view the Department of Energy’s annual market report at Offshore Wind Market Report: 2022 Edition | Department of Energy.

Amy Fischbach is a freelance writer based in Overland Park, Kan. She can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

Amy Fischbach

Amy Fischbach is a freelance writer, editor, and host of the Line Life Podcast based in Overland Park, Kan. Contact her at [email protected].