Electrical inspectors are an important safeguard toward the safety of an electrical installation. Today, we are seeing various individuals who conduct electrical inspections. Some are multi-hat inspectors who are tasked (in many cases, not by their choosing) with inspecting all aspects of building-related construction within their jurisdictions. Others are true electrical inspectors, building inspectors, industrial facility engineers, fire marshals, or commanding officers at a military base. All of these individuals make up the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ), which is a defined term found in Art. 100 of the National Electrical Code (NEC).

During the daily duties of their jobs, electrical inspectors inspect several types of electrical installations. Whether it’s residential, commercial, or industrial applications, these individuals must have a keen understanding of the NEC rules in all of these areas of construction. To be proficient at their work, they must have a working knowledge of the NEC and several other industry documents that govern or provide insight into electrical safety. The International Association of Electrical Inspectors (IAEI) as well as other industry associations in the electrical industry provide certification opportunities for individuals to demonstrate they have a firm understanding of these various requirements.

This article will review 10 of the top-cited violations from around the country based on feedback from electrical inspectors. In many instances, these violations are consistent in many regions.

Violation #1. Conductor Box Fill Issues

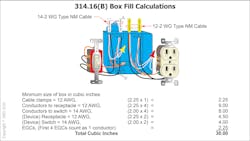

Ask some installers how many conductors an electrical device box can contain, and you might get the answer “as many as I can get in the box and still get the switch or receptacle to fit.” Hopefully, this is not the case in your area of the country. All boxes must be large enough to provide sufficient free space for all enclosed conductors to prevent overcrowding and possible physical damage. Information is provided in Sec. 314.16 to assist the installer and the inspector in determining the correct conductor fill for these installations. Table 314.16(A) provides box dimension and trade sizes (in inches) for standard metal boxes.

All nonmetallic boxes must have their cubic inch capacity durably and legibly marked by the manufacturer inside the box. Figure 1 shows an example of how to work through a box fill calculation.

Violation # 2. Bored Holes in Wood Framing

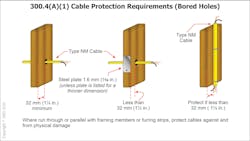

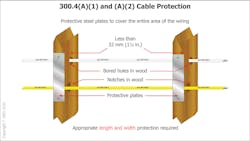

One of the most common violations in residential installations involves the installation of nonmetallic (NM) cables through wood framing. The International Residential Code (IRC) contains a lot of information about the removal of framing material through notching or boring methods. This information is needed to ensure that the tradesperson does not remove too much of the framing material, thus weakening the structural integrity of the building. The NEC also provides guidance in Sec. 300.4 on protecting these cables against physical damage. A steel plate is needed where the edge of the hole is less than 11/4 in. from the nearest edge of the wood member. The steel plate must be at least 1/16 in. thick (unless the plate is listed), and long/wide enough to cover the area of the NM cable. Figures 2 and 3 provide additional guidance concerning this requirement.

Violation # 3. Improper Torquing of Terminations

The tightening of conductors is sometimes taken for granted. Many electricians have been taught that their elbow contains this “magical” ability to sense when the appropriate amount of force has been applied to the tool tightening the electrical termination. This was tested a few years ago at a trade show by a wiring manufacturer. The attendees were mostly all seasoned electricians. They were given an opportunity to tighten electrical terminations with a standard wrench to the level they thought it was tightened properly. A staggering 78% of these terminations were under torqued. Now think how many times you have done exactly that same thing. This is why torquing and using the proper tools is important to the electrical safety of the installation.

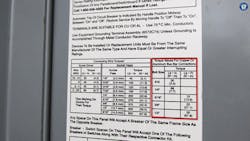

Requirements located in Sec. 110.14(D) specify an approved means to be used to reach the torque value for electrical terminations. These values are indicated on the electrical equipment or can be found within the installation instructions provided by the manufacturer. Examples to determine that the proper torque has been applied include torque tools or devices such as shear bolts or breakaway-style devices with visual indicators.

Each state or electrical jurisdiction will need to be consulted on how they want to verify the installer has conducted the required torquing of termination for their electrical installation. This varies from watching an installer use a torquing tool correctly on some of the terminations to requiring a signed document attesting that the electrical terminations have been torqued per the manufacturer’s requirements. It is imperative that the electrical professional knows how to properly utilize these tools. Figures 4 and 5 show information concerning torquing requirements.

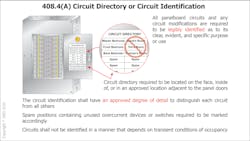

Violation #4. Lack of Proper Circuit Identifications for Panelboard Schedules

One critical item that needs to be completed on most electrical projects is a properly and legibly labeled circuit directory. This ensures that the homeowner, business owner, or maintenance person knows which circuit breaker controls each of the branch circuits in the dwelling/building. Requirements found in the Sec. 408.4(A) will help you with this process. Make sure that the labels do not depend on transient conditions. For example, David, Tim, or Thomas may currently occupy a bedroom in the house but may not in the future. If these are bedrooms or office locations, label the circuit directory appropriately, such as NW second-floor bedroom or first-floor master bedroom. In addition, do not put the symbols used by the electrical industry down for receptacles and switches. It is almost guaranteed that the homeowner or office tenant will not know the meaning of these symbols. See Fig. 6 for additional information.

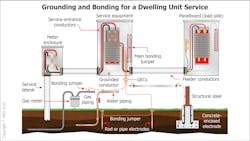

Violation #5. Grounding and Bonding Between the Service Disconnect and Feeder Panelboard

Grounding and bonding of electrical equipment is by far one of the most misunderstood requirements in the NEC. Many times, it is because someone was taught something incorrectly, and they have continued doing it over and over throughout their careers. It starts with the use of properly defined terms for the various components.

Not everything used for grounding and bonding can be referred to as “that ground wire.” Many questions asked during IAEI meetings or via email must first go through the proper use of definitions, which are listed in Art. 100 of the NEC. See Fig. 7, which contains the proper names of many of the components that are encountered when bonding and grounding a system.

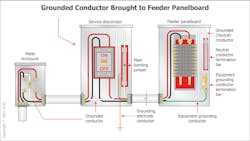

Improper bonding of the neutral in the feeder panelboard is a common violation. As can be seen in Fig. 8, the grounded conductor (neutral), the grounding electrode conductor (GEC), and the main bonding jumper are connected at the service disconnect.

Once the feeder conductors are installed from the service disconnect to the feeder panelboard, these connections are different. In our case, the ungrounded conductors are terminated at a main lug-only (MLO) feeder panelboard. The grounded conductor (neutral) is installed on the neutral terminal bar that is intentionally isolated from the metal panelboard cabinet. The EGC from the service disconnect to the feeder panelboard is installed on the EGC terminal bar that is solidly attached to the metal panelboard cabinet.

Violation #6. Missing or Improper Field Labeling

The NEC contains field labeling requirements for new and reconditioned equipment. If labels are not provided or are illegible, maintenance personnel and other electrical professionals who are called on to troubleshoot electrical problems will struggle when trying to disconnect pieces of equipment from the system.

Some facilities operate with the same electrical crew for decades. These individuals have installed and maintained the electrical system for years. Then, the unthinkable happens. The maintenance staff is no longer there. Some have retired, others have experienced a life-changing event and are no longer available, and some have passed away. This information was embedded in their brains or in files that have been discarded. With the absence of a simple label, many hours are spent trying to figure out how to isolate or disconnect electrical equipment.

Proper labeling is important to ensure that future electrical professionals can work safely and efficiently on the electrical system. It only takes a few minutes longer to make a label or order one for the equipment. This small act is important and can save time, reduce downtime, and increase worker safety (see Fig. 9).

Violation #7. GFCI Protection for Kitchens (Other than Dwelling Units)

Many electrical professionals understand the GFCI protection requirements for kitchens when it pertains to dwelling units [Sec. 210.8(A)(6)]. But there are instances where inspectors are finding violations when it comes to requirements in Sec. 210.8(B)(2) for other than dwelling unit kitchen areas. This commonly involves the 208V receptacle outlets up to 150V, exceeding 50A. In some cases, the GFCI protection for these locations is difficult to find or more expensive than conventional GFCI protection means. Figure 10 further explains these requirements.

Violation #8. Working Space Violations

This violation is common after a building has received its final inspection and been occupied. Very few times does the electrical professional knowingly violate these requirements because deep down they are conscious of the dangerous effects of electricity. Let’s face it — they are the ones being called to work on this electrical equipment and know they need sufficient room to do so in a safe manner.

Many times, this is violated by the building occupants that see a nice clear space in a closet that looks perfect to store paper towels, cleaning supplies (including the cart), or holiday decorations. A yearly fire inspection might flag this and point out the violation to the occupants who honestly were unaware they were violating any safety rules.

Electrical equipment is required to have working space per the requirements found in Sec. 110.26. This space is to be provided and maintained for safe operation and maintenance of the equipment. Electrical equipment is not just panelboards and switchgear. It is equipment that is operating at 1,000V nominal or less that is likely to require examination, adjustment, servicing, or maintenance while energized (see Fig. 11).

Violation #9. GFCI Devices Installed in Non-Readily Accessible Locations

While waiting on my baggage at the airport recently, I observed a gentleman getting physical with a vending machine. At first, I thought he was upset that his product had not been dispensed and was trying to shake it loose. The more I observed the situation, the more I saw he was trying to work the machine out of a wooden display frame enclosure that contained four individual vending machines. This gentleman did not weigh more than 180 pounds. He reminded me of a small frail football player trying to move a huge offensive lineman. He was not having very much luck. After receiving my luggage, I went in his direction and offered to help him. In speaking with him, he told me he was an electrician. I asked if he was moving the machine to get to the GFCI protective device behind the unit. He was surprised that I knew what he was doing and said yes. He said that two of the machines were not working, and, in the past, it was a tripped GFCI receptacle behind the machines. He squeezed behind the vending machine and used the flashlight on his phone to find the receptacle. He pushed the reset button, and both vending machines came on.

There is language in Sec. 210.8 specifying ground-fault circuit interrupters (GFCIs) to be installed in a readily accessible location. The definition of readily accessible can be found in Article 100 of the NEC. This was a perfect example of why NEC Code-Making Panel 2 put this requirement into the Code. The installer should have provided GFCI protection in a location that would not require equipment such as vending machines (Photo 1), ice machines, or refrigerators full of items to be moved to access the receptacle. This GFCI protection could have been installed within the electrical panel or readily accessible on the outside of the wooden display frame enclosure. I’m sure the electricians or technicians out there that have to move this heavy equipment will greatly appreciate this rule.

Violation #10. Covering or Concealing Electrical Work Before Electrical Inspection

Many times, the electrical contractor is under tremendous pressure to get their installations inspected so that backfill or wall covering can be installed. It is important to make sure that inspections are completed and any corrections necessary are finished before covering up the electrical system components. Typically, this occurs only once because the contractor does not want to uncover the conduit or remove the wall covering materials so that the inspection can be completed and approved (see Photo 2).

Final thoughts

Contrary to what is discussed on construction sites, the electrical inspector is not out to give the electrical contractor or installer a hard time. Although I’m sure there are exceptions, electrical inspectors are tasked with a job — and are responsible for making sure electrical installations meet the minimum requirements stated in the NEC.

Many of these inspectors were employed as electricians and installed electrical equipment before becoming electrical inspectors. They have been on both sides of this relationship and understand the needs of the installer and requirements of the NEC. They are an instrument in place to assure that your installation meets the minimum requirements found in the NEC.

But make no mistake, the installer is the first set of eyes that ensures electrical safety. The electrical inspector is a second set of eyes that helps assure the public is safe while in the presence of electrical installations. In many cases, they are expecting the installation you have completed to be correct as they usually do not have time to make reinspections. Just as there is a shortage of skilled electrical installers, there are often shortages of inspectors due to budget constraints within state and municipal inspection departments.

It’s also important to note that some states and jurisdictions enact other electrical ordinance requirements that supersede the NEC. These requirements must also be met. For example, a popular ordinance in many areas of the country is for deeper ditch requirements for underground electrical installations. This is required due to damage from other contractors or the homeowner when installing other utilities, sprinkler systems, or fence posts. Before starting any underground installation, call for utility locations to be marked. This will give you guidance on where these underground services are located and help you avoid them — and the cost associated with repairing these damaged systems.

Joseph Wages, Jr., is the digital education director at IAEI. Previously he has held the positions of technical advisor, education, codes and standards, and seminar coordinator at IAEI. He represents IAEI on NFPA’s NEC Code Making Panel 2 for the 2020 and 2023 NEC code cycles. He previously represented IAEI on NFPA’s NEC Code Making Panel 3 for the 2014 and 2017 NEC. He serves on the Underwriters Laboratories (UL) Electrical Council and several UL Technical Standard Panels. Joseph continues to hold state electrical licenses and several IAEI and ICC building-related certifications. He can be reached at [email protected].