In simple terms, building codes and standards are about protecting people and property — the result being safe and prosperous communities, which is the heartbeat of any culture. Every rule in every building code and related standards, whether it be a plumbing code, the Fire Alarm Code, or the National Electrical Code (NEC), is written to protect the health and welfare of people and to provide safe structures.

For example, Sec. 90.1 of the NEC states its purpose as, “… the practical safeguarding of persons and property from hazards arising from the use of electricity.” It states nothing about passing inspections, sizing conductors, or complying with local requirements. Certainly, following the rules of the Code, manufacturer’s instructions, and state and local jurisdiction requirements will get us through the project, but every rule in the NEC is all about creating electrically safe environments for the public and the workers in plants and facilities.

In 1859, the first building code was instituted in the United States by the city of Baltimore. Code evolution continued, and by the 1990s three primary building codes (based upon geographic regions) were in use across the United States. The need to consolidate building codes resulted in the creation of the International Code Council (ICC). These International Codes, the “I-Codes,” are a series of building codes addressing various aspects of the built environment and are used throughout the United States and some foreign countries (see Sidebar below).

Codes and standards are written by Standards Development Organizations (SDOs). These are the administrative bodies that coordinate the groups of technical experts who work together to produce our codes and standards. While the terms “codes” and “standards” are sometimes used interchangeably, “codes” are written in language to be adopted as law while “standards” may provide us performance requirements or detailed information about a specific topic. For example, the requirements for generator installation are found in Art. 445 of the NEC. Where the NEC is enforced as law, generator installations must follow these rules and any local requirements. The NFPA 110, Standard for Emergency and Standby Power Systems, may be used by the authority having jurisdiction (AHJ) to define how much fuel must be available for the standby system or the maximum time allowed from loss of normal power until the emergency system is delivering power.

Codes and standards developed in the United States are based on a consensus of experts with input provided by any individual in the world who desires to recommend changes and improvements to the documents. To understand where these technical experts come from, look no further than the front portion of the NEC and review the exhaustive list of committee members and the varied organizations they represent. No matter the code or standard published, the number of committee members, or what body they represent, the document is considered to be a voluntary consensus standard because of the process by which it is developed. The use of a voluntary consensus process forms the foundation for the design and construction of our built environment.

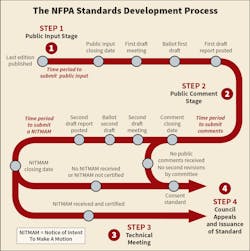

The NFPA voluntary consensus process for the development and revisions of codes and standards demonstrates the “openness, balance, consensus and due process” required by ANSI. Upon publication of a standard, the next revision cycle begins with the solicitation for public input. All such input is addressed and responded to by the Technical Committee. Through the process, draft reports are issued and a formal, final appeals process occurs before the code or standard is finally issued by the Standards Council.

For just over 100 years, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) has worked with SDOs to ensure development processes meet the ANSI requirements for “openness, balance, consensus and due process.” ANSI also accredits codes and standards to ensure these requirements have been met. The codes and standards published by the NFPA are examples of ANSI-approved standards. This process for openness, public input, and comments is evident when observing the development process for the NFPA standards (see Figure).

The NEC has become an integral part of overall building code requirements. Though some I-Codes, such as the International Building Code (IBC) and the International Residential Code (IRC), reference the current NEC, each also contains specific I-Code rules for electrical installations. At first, this may appear to present confusion when installing electrical equipment. The question is: Do the written rules in the I-Codes conflict with the NEC?

Mark Earley, NFPA chief electrical engineer and secretary of the NEC explains why not: “NFPA has provided the text for the I-Codes to meet the ICC format requirements. By providing this electrical information we are able to keep the NEC in sync with the I-Codes.” In fact, Earley notes the term “International Electrical Code Series” appears on the front cover of the NEC to “facilitate other countries in adopting the NEC.”

Having the I-Codes and NEC in sync with each other prevents conflict and confusion and is critical for electrical designers, contractors, and electricians. I-Codes are updated every three years.

The NFPA 5000 Building Construction and Safety Code was first published in 2002 and was the first model building code to receive accreditation by ANSI. It also references NFPA 70E, the NEC, and other codes including the NFPA 72 National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code. Chapter 52 Electrical Systems of NFPA 5000 states: “All electrical equipment and systems shall be designed and constructed in accordance with NFPA 70.”

The number of SDOs and their associated standards is too numerous to address in their entirety in this article. For example, of the more than 300 codes and standards published by the NFPA there are many that affect electrical construction and maintenance work. NFPA 72, Fire Alarm and Signaling Code, NFPA 99, Health Care Facilities Code, and NFPA 101, Life Safety Code, are typical examples of such codes. See the Sidebar below for examples of codes and standards that often apply.

With so many codes and standards, the term “incorporation by reference” is commonly used throughout various building codes and in governmental requirements. Governmental acts have permitted the government to incorporate Codes and Standards as part of federal regulations. For example, OSHA 1910.6(a)(1) states, “The standards of agencies of the U.S. Government, and organizations which are not agencies of the U.S. Government which are incorporated by reference in this part, have the same force and effect as other standards in this part.” OSHA can cite both the NEC and NFPA 70E, Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace. Both NFPA documents are listed in the references Appendix A of OSHA regulations Part 1910, Subpart S Electrical.

This continually brings up one issue regarding codes and standards published by the SDOs: If a code or standard is enforceable as law, and you cannot copyright the law, then codes and standards should be free and have no associated copyright, correct? Not really. All works of authorship are protected by the federal Copyright Act of 1976. This includes the many standards developed by the SDOs. There are no special provisions issued by the government for standards incorporated by reference. In fact, it is important to realize the valuable service provided by the SDOs. Consider how the various standards and codes affect the development of OSHA regulations. Because of documents such as the NEC and NFPA 70E, OSHA has access to the information and recommendations from a countless number of subject matter experts in specialized areas. How large and unmanageable would OSHA regulations become should they have to duplicate and maintain the same wording found in the referenced documents?

Additionally, consider the work required by the SDOs. The voluntary consensus processes used by the ICC and NFPA for building codes, the NEC and various other codes and standards all require resources and manpower, meetings, administrative needs, editing, review for compliance with other standards and, publication and distribution. Though committee members are volunteers, the many standards organizations who develop our codes must maintain the financial side of their business to continue their work. Considering the importance of human life and welfare — and the need for safe occupancies of all types — these organizations provide us more than a fair return when investing in their products.

Discussing new technologies and when asked if technology has an impact on codes and safe buildings and communities, Earley remarked, “This is definitely true and becoming a truer statement all the time because of advancing technologies around us. New technologies are being added to standards all the time. Just look at the recent article additions to the NEC over the past several editions. The NEC committees are challenged to keep up with these advances.”

What about jurisdictions that fail to use the latest codes and standards? “They will just continue to fall further and further behind,” Earley says.

Considering the number of technical experts, the varied public input, and the ever-changing technologies, jurisdictions are always encouraged to use the most current codes and standards to provide the greatest level of safety in the built environment. The need for voluntary consensus standards to provide safe communities is obvious. Interpreting and applying these documents is the role of all those involved in electrical work. This includes designers and engineers, AHJs, electrical contractors, construction electricians, plant maintenance organizations, and electrical maintenance workers. The process to develop these codes and standards has evolved and improved over many years to give us our current installation standards. Protecting the health and safety of the public and creating safe buildings in our communities is the reason for code compliance. Everyone must exercise the self-discipline and integrity to ensure our codes and standards are properly applied.

Barnett is a certified electrical safety compliance professional (CESCP). He can be reached at [email protected].

Sidebar: The ICC and NFPA Provide the Foundation Documents for Safe Built Environments

Commonly Used NFPA Codes and Standards Affecting Electrical Construction and Maintenance

• NFPA 70 National Electrical Code

• NFPA 70A National Electrical Code Requirements for One- and Two-Family Dwellings

• NFPA 70B Recommended Practice for Electrical Equipment Maintenance

• NFPA 70E Standard for Electrical Safety in the Workplace

• NFPA 72 National Fire Alarm and Signaling Code

• NFPA 73 Standard for Electrical Inspections for Existing Dwelling

• NFPA 77 Recommended Practice on Static Electricity

• NFPA 78 Guide on Electrical Inspections

• NFPA 79 Electrical Standard for Industrial Machinery

• NFPA 99 Health Care Facilities Code

• NFPA 101 Life Safety Code

• NFPA 110 Standard for Emergency and Standby Power Systems Emergency and Standby Power Systems

• NFPA 780 Standard for the Installation of Lightning Protection Systems

• NFPA 790 Standard for Competency of Third-Party Field Evaluation Bodies

• NFPA 855 Standard for the Installation of Stationary Energy Storage Systems

• NFPA 5000 Building Construction and Safety Code

The ICC “I-Codes”

• International Building Code

• International Energy Conservation Code

• International Existing Building Code

• International Fire Code

• International Fuel Gas Code

• International Green Construction Code

• International Mechanical Code

• International Plumbing Code

• International Private Sewage Disposal Code

• International Property Maintenance Code

• International Residential Code

• International Swimming Pool and Spa Code

• International Wildland Urban Interface Code

• International Zoning Code

• ICC Performance Code

The I-Codes reference the National Electrical Code (NEC) for the electrical portion of the applicable building code. Specific electrical rules found in the I-Codes are in sync with the NEC. The NFPA publishes more than 300 codes and standards. In addition to the NEC, construction and maintenance personnel often find themselves applying portions of other standards to install and maintain electrical equipment and systems.