Employing proven design, microgrids are all but destined to be a part of the nation’s future electrical infrastructure. But gaps in supportive policy could act as a powerful brake on their development and hinder their path forward.

Surveying the ground in all 50 states, Think Microgrid, a Boulder, Colo.-based microgrid advocacy organization, concludes that all but a handful are sorely lacking the regulatory and statutory framework needed to give powerful impetus to a timely build-out of a robust microgrid infrastructure. Its findings are summarized in a state scorecard report issued in early November — one that paints a picture of an inspired energy production and distribution concept in danger of being held hostage to foot-dragging, inertia, lack of planning, and entrenched interests.

“Policy, not technology, remains the limiting factor for microgrid commercialization,” the report states.

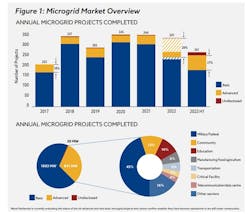

Rating each state on a set of five criteria deemed central to microgrid support and development, the report finds only four attaining a “B” grade: Hawaii, Texas, Colorado, and Connecticut. Fifteen states and Puerto Rico got a middling “C” grade. The rest were given a barely passing “D” grade. Whether it’s the current state of deployment; the presence of proactive policy; a commitment to energy resilience; the existence of grid interface platforms; or a strong community equity approach to energy investments, most states don’t currently have anything close to the foundation needed to bring more microgrids into the picture on any kind of expedited timeline. And that may be slowly exacting a toll on microgrid deployment, which has been tailing off since 2020 (see Figure below).

Describing the challenge, the report observes that “most states have not identified significant and meaningful strategies for incorporating microgrids into the physical grid and creating market designs necessary to support them. Microgrid policies that do exist — including incentives/programs, retail microgrid tariffs, and resilience planning processes — are often severely limited in scope.”

While many states can be applauded for taking a more proactive stance on building an energy infrastructure to address the issue of the day (climate change), too few are up to speed on understanding the role that microgrids can play in that effort by utilizing alternative energy, storing power, and relieving pressure on fossil fuel-heavy utility generation. Given the stakes, the report says there’s an urgent need to bring more online, but the barriers are high.

“Many states have responded to climate challenges by prioritizing decarbonization, equity, and economic development benefits. However, state legislation and policy have generally prevented the commercialization and enablement of microgrids that can maximize resilience, decarbonization, equity, and economic development.”

Allan Schurr, chief commercial officer with Enchanted Rock, a Houston-based developer of resilience microgrids, and a Think Microgrid founding member, views mounting concerns over the adequacy of power redundancy as one of the leading drivers of future microgrid development. And much of the impetus for that will have to come from policy developed at the state level to address risks to life and property that accompany the prospect of extended power outages.

“We’re more dependent than ever today on electricity, and because we’re starting to realize how fragile the grid is the need is greater now than ever for what microgrids can offer,” he says.

One obvious gap that microgrids might be able to play in the resiliency challenge immediately, Schurr notes, is in emerging as a replacement for diesel-powered generators. Though carrying a higher up-front price tag, microgrids that provide power in isolation from the grid offer a host of long-run advantages in reliability, climate-friendliness and maintenance requirements over generators that can sit idle for long periods.

“We may be coming to a tipping point with generators, which are much dirtier and limited by the amount of fuel on site and may not be reliable if not exercised and tested regularly,” he says. “Microgrids might be a better option than traditional backup power.

As one of numerous examples of state dysfunction, the report highlights the California Public Utilities Commission’s (CPUC) refusal in April of last year to hold a hearing on a detailed plan to develop privately owned microgrids for residential communities. Think Microgrid says the denial is seemingly at odds with a 2018 state “micro-utility” statute directing the commission to facilitate microgrid commercialization in the state, which earned a “C” on the report scorecard. So far, it claims, CPUC has largely restricted its facilitation efforts to utility-owned microgrids.

The decision further proves that “California is hostile to distributed energy,” says Cameron Brooks, Think Microgrid’s executive director. “It’s a prime example of a state that seems to be in the throes of incumbency influence.”

The consequences of California’s stance are tangible, Brooks says. With the state seemingly blessing utilities’ plan to put more power lines underground to limit fire risk, microgrids are being overlooked as a possibly superior solution. “Some economists are saying microgrids would cost 10% of what it would take to bury power lines.”

That underappreciation of microgrids, possibly stemming from a lack of basic knowledge and understanding, forms part of the logjam microgrids face at the state level. The task for microgrid interests, knowing the importance of fertile ground development, Brooks says, will be keeping a close eye on the distributed energy policy trajectory and leaning heavily into advocacy for microgrids and microgrid-friendly stances at multiple levels.

“All states have an opportunity to take better advantage of what microgrids have to offer (and align with) what the U.S. Department of Energy says is a distributed energy future where up to half of the nation’s power comes from the distributed resources,” he says. “Microgrids are key to aggregating that, but as of now we’re nowhere close to that aligning with that vision.”