Better Data Strategies Could Save the Construction Industry Money

The old “garbage in, garbage out” scenario is playing out in the construction industry’s relationship to data, causing costly waste, errors, and miscalculations that weigh heavily on contractors’ abilities to deliver projects efficiently. That’s the general conclusion of a recent study issued by FMI Corporation and Autodesk, “Harnessing the Data Advantage in Construction,” the latest in a growing body of research that urges the construction industry to start prioritizing a data-centric approach to its business.

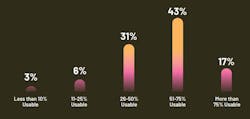

The report, based on a survey of some 3,900 global construction industry stakeholders, concludes that while the amount of raw data accessible to the industry is growing – an overall promising development – so much of it is “bad,” meaning incomplete, inaccessible, inaccurate, inconsistent, or untimely, that its value is eroded because it can’t be used to provide usable information or actionable insights (see Table below).

In a press release announcing the study’s release, Autodesk, a construction software provider, says bad data may be costing the global construction industry close to $2 trillion annually, a staggering amount that shows up in the form of productivity reductions, rework, project delays, budget overruns, change orders, and safety-related slowdowns. Bringing that impact down to the level of a typical large contractor, the study estimates that the cost of bad data to one with $1 billion in annual revenue could equal $165 million. Assuming a typical contractor of that size incurs $50 million in rework costs annually, the study suggests $7 million of that could be traceable to reliance on bad data.

The study found that the industry is becoming more reliant on data, on its face a good development given the need for utilizing data; the consensus was that the volume of available project data has doubled in the last three years, and three-quarters said there’s a growing need for rapid decision making in the field that’s dependent on strong data. The other part of the story is that 30% said probably half of the data they collect is bad. But only 36% said they’ve taken steps to identify and repair bad data.

The upshot of the report is that the construction industry, faced with a pressing need to sift through more and more data to glean critical information, needs a comprehensive strategy for data collection and management. Contractors, says Allison Scott, director of construction thought leadership for Autodesk Construction Solutions, can benefit from implementing “formal data strategies to gain the most ROI from their technology investments (and) collaborate with vendors to determine how to make the best use of the data being collected."

The study’s findings and blueprint for action resonate with Dave Crumrine, president of Sioux Center, Iowa-based electrical contractor, Interstates, Inc. Convinced of the growing need for construction contractors to begin looking at their functions through an industrial processes prism, the company is prioritizing the collection of sound and reliable data and better understanding of how to use it to improve the project delivery process. Data is at heart of that effort because, properly amassed and interpreted, it produces the information needed to develop and institute tested efficient processes that can be repeated project after project.

“In the construction industry’s craft mindset, every project is unique and attacked as a custom thing,” Crumrine says. “We take the approach that we’re building these snowflakes, and everything is custom -- so you can’t apply what you learn to the next project.”

But that’s not the case, he says, because construction does in fact rely on many established processes and tasks that can be scaled and adapted as needed, much as a typical auto manufacturer is capable of building numerous, very different models on a single assembly line. Capturing data related to those processes and smartly analyzing it forms the foundation of a new industrial approach to construction, but it’s something that’s been slow to develop because of the industry’s project-focused mindset.

“The ability of the industry to collect data has been one of the big barriers,” Crumrine says. “We send people out to put in conduit for instance, and we get how much foot per hour is installed, but there’s so much more to know. What we end up relying on mostly is analogies and stories, but no hard data.”

Data contains the seed of answers to a multitude of problems, Crumrine says, but only if the right questions are asked. Contractors should start with an “I wonder,” statement that frames the inquiry that data might help satisfy, such as “I wonder if pre-fabbing brackets would save us money,” he says. From there, a deep dive into data might yield an answer. “If you don’t start out with that wondering approach data can be a sea of chaos.”

Interstates, Crumrine says, is moving to become one of the “haves” in the electrical contracting industry when it comes to data analysis capabilities, a posture that should work to its favor in a future where data is more critical in the industry. The company has prioritized taking an “open” approach to software that will allow it to integrate its own data management processes into the product and is contemplating adding more data specialists into its ranks, Crumrine says. It’s a more proactive and serious approach to data that more contractors will need to adopt in the future, he says.

“Our industry is very wasteful,” Crumrine says. “Data can provide the insight that can help us attack that problem.”

In addition to the survey, read “The Ultimate Guide to Leveraging Data in your Construction Lifecycle.”

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].