Everyone knows that if you plan work early, you will be more productive and profitable on a project. It’s also a well-known fact that it’s difficult to plan and run a construction job because of ever-changing job-site realities, which are often impossible to predict. However, based on MCA’s inhouse experience, research has shown that by using the fully integrated Work Environment Management® methodology every hour of planning can save up to 17 hours on job operations. The real question is: How can you successfully and realistically implement job planning before the job even starts?

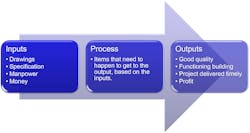

Before diving into the actual “how-to” of planning, let’s review the basics of a project. Every project has certain inputs and outputs (Fig. 1). The steps between the input and the outputs are all the items that need to happen to achieve the outputs. To be able to predict the outcome, as well as to design the process steps as efficiently and profitably as possible, the outputs and inputs need to be clear and understood by everyone on the project team. This can be achieved through good project planning.

Project management is risk management. It is in and of itself a profession, yet many field leaders become blessed with this title because they are good job managers. Project managers cannot assure predictable projects without starting off on the right foot.

The actual execution of project planning needs to happen in a structured and repeatable way that doesn’t depend on the experience or habit of a single person. Many companies have tried to implement a structured information exchange (e.g., kickoff meeting, pre-planning meeting, handoff meeting, or startup meeting). While most people agree that project startup meetings are great and help the job to be more productive, companies struggle to ensure that the meetings are happening in the correct structure, so the right people get the full benefit out of the meeting. To ensure the project startup meeting is beneficial, the following process steps need to be owned and followed by the project managers.

Independent of the size of the job, the information that the estimator knows needs to be transferred to the right people and positions. Therefore, the first step is to:

1. Define your project support team. Who needs to be involved?

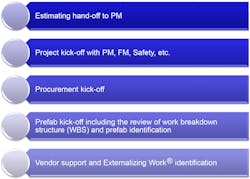

Possible functions to consider are project manager (PM), foreman, field leader, estimator, prefab manager, procurement manager, BIM/VDC contact, safety manager, tool/equipment manager, and vendor partner (Fig. 2). The number of people involved in the meeting mainly depends on the size and risk of the job. It can be as simple as having the PM (who was also the estimator) and the foreman get together. Ideally, all of the different functions shown in Fig. 2 should be involved in the meeting and part of the project support team.

After the project support team is identified, the next step is:

2. Define content and timing of information to be shared. Who needs to know what, by when?

Two different approaches can be used to answer this question. In the first approach, everyone should hear everything about the project. Although this method may be more time consuming, it could benefit the whole project team by avoiding information exchange misses and helping increase the company’s cross functional learning.

The second approach focuses on the fact that certain topics are mainly relevant for certain people. In this case, it needs to be defined who should know what, by when. The general strategy is to pass on the information as early as possible to ensure that the planning and layout can happen as early as possible and open questions can be addressed. Now it’s time to address the type of meeting to be held.

3. How should the meeting be conducted?

Generally, there are three different options available. The information exchange can happen in one meeting, where all project support team members (Fig. 2) participate in the full length of the meeting. Another option is to hold one meeting that covers all the necessary topics, but participants join and leave at different times, depending on the discussed topic. The third option is to hold separate meetings for the different project topics. As illustrated in Fig. 3, this could include, for example, an estimating to PM hand-off; a project kickoff with PM, FM, safety, etc.; a procurement kick-off; a prefab kick-off, including the Work Breakdown Structure (WBS) review and prefab identification; as well as a vendor services and Externalizing Work® identification. The information exchange itself should happen in person as much as possible or via video conference to ensure immediate information exchange without communication barriers or losses.

Having the meeting type and participants defined, the next step is to specify the meeting content.

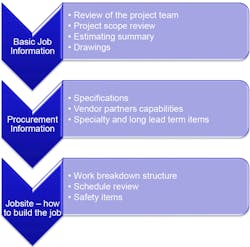

4. What is the agenda for the meeting(s)?

The agenda(s) should include all items that need to be discussed, including the outcome of the meeting (Fig. 4). Depending on the size and the potential risks of the job, the meeting duration can be either longer or shorter. If you are planning to have multiple meetings, define the agenda for each of the meetings. It is important to pass on the agendas to the participants ahead of time along with a notification about what each participant must prepare for the meeting. It is beneficial if basic job information sheets are filled out and distributed ahead of time to ensure every team member can become familiar with the job before the meeting. This can be done by sending out the meeting invites, including the agendas and supporting documents to the team. By now, most of the logistics and preparation for the meeting has been done. Before the actual meeting can be held, however, there is one more item that needs to be defined.

5. Who will be taking notes and assigning action items?

How many times have you been in a meeting where a great discussion occurs, but after the meeting ends nothing happens with this information and no actions are taken? To keep this from happening, it’s important to have a dedicated person who takes notes and assign action items at the meeting. Project startup meetings usually raise many questions, which can slow down the meeting if the participants try to answer them immediately in detail. By noting them and moving on, the items can be registered and followed up afterwards without derailing the structure of the meeting.

Now that all items in steps 1 to 5 have been identified and completed, the actual meeting or meetings can be held. Before the end of the meeting, all the action items need to be reviewed, including the responsible person and due dates assigned for each item. The notes and action items should be distributed to the whole team. In a best-case scenario, the notes are stored on a shared space so everyone can reference them later and add any updates or additions. The project will be changing and so will the action items and next steps, which requires updates and adjustments on a regular basis. This task is owned by the project manager and can be managed through an “open item list.”

The last item before any meeting is adjourned is to define the next steps and schedule follow-up meetings. Every item on the agenda should be reviewed to identify if a follow up meeting is needed, and when and with whom it should be scheduled. In most cases, prefab or procurement follow up meetings need to be scheduled. Depending on the size and complexity of the job, recurring meetings can be set up with the project team and different supporting departments.

Now your project team is set up to start the project on the right foot. Figure 5 summarizes the steps for a successful project startup. The PM is the one who needs to take the lead and drive the startup process to ensure it is done correctly and in a timely fashion. Figure 6 summarizes “do’s and don’ts” for a startup meeting.

In summary

As stated earlier, project management is risk management, and therefore it is important for the project manager to share the project goals with the team, define a detailed plan on how to get there (WBS), and ensure that the whole project team has correct and timely information to support a successful and profitable job. A good and timely project startup meeting is key to a good and productive project. By being able to identify the risks and open questions and potential complications up-front, the project team can plan, predict, and prevent (and therefore avoid) productivity loses and obstacles. With good project planning, the profitability of the job can be increased tremendously and overall safety can be secured.

Dr. Perry Daneshgari is the founder, president / CEO of MCA Inc., a research and implementation company based in Grand Blanc, Mich., that focuses on implementing process and product development, waste reduction and productivity improvement of labor, project management, estimation, accounting and customer care. He can be reached at [email protected]. Sonja Daneshgari is field operations manager for MCA Inc. She can be reached at [email protected].