Electrical Contractor Productivity Examined

As the recession began to hit the nonresidential construction sector, productivity improved significantly, largely due to companies doing more with fewer people. Those employees not hit with downsizing were likely the most experienced and best-trained personnel as well. However, those immediate improvements, due mostly to downsizing and working harder, begin to wear off in time. While productivity continues to improve even though business is struggling, the rate of improvement is slowing. Continued improvement will come from strong leadership and management, better and more consistent management processes, new delivery methods like integrated project delivery (IPD), tools and technologies like building information modeling (BIM), and formal training/development programs for project managers (PMs) and field managers. These improvements will require significant investments at a time when margins and profitability are strained.

Perceptions of Productivity

The following summary of FMI’s “2012 U.S. Construction Industry Productivity Report” includes additional comparisons broken out for electrical contractors participating in the survey. However, it’s important to note that the percentage of respondents identifying themselves as “electrical contractors” represented only 12% of all responses. A few of those were also mechanical contractors and performed other subcontracting work. Although we cannot claim that this small sample represents the practices of a larger number of electrical contractors, from our firm’s field experience, we note this sample is not atypical of larger electrical contractors in the business. Generally, electrical contractors face the same productivity challenges as the other trades do — the differences in certain areas are just a matter of degree.

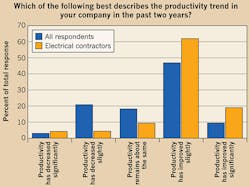

Companies across the industry measure productivity in different ways. To compare trends across different metrics, the survey did not ask questions tailored to specific metrics. Instead, it asked for the respondent’s professional opinion as to what degree productivity in his or her firm has improved, decreased, or stayed the same.

More than half (57%) of the participants responded that productivity had improved either slightly or substantially in the past two years, while the remaining 43% reported it had stayed the same, decreased slightly, or decreased substantially. Nineteen percent of electrical contractors said productivity had improved significantly, while 61.9% said productivity improved slightly (Fig. 1). Some of this improvement is simply the result of downsizing, where the marginal performers were the first to be laid off. Because of washing out the lower-level performers in the field and project management, the average performance level naturally increased. However, while productivity improved for more than half of respondents, it did so only slightly for the majority, leaving ample room for improvement across the industry. Furthermore, 90% of electrical contractors believed they could save at least 5% of their annual field labor cost through better management (Fig. 2). For a contractor with $20 million in annual field labor cost, this represents a $1 million profit opportunity!

Seventy percent of participating companies (67% of electrical contractors) reported experiencing cost overruns on at least 11% of projects (Fig. 3). FMI believes that this self-reported data is extremely optimistic. From our consulting experience, the actual data from analyzing thousands of completed projects suggests that well over half of all projects fail to meet or beat the labor estimate. Clearly, there is an opportunity for companies to make improvements in productivity that will improve their ability to achieve labor budgets, which, in turn, will improve the bottom line.

Project Planning Processes

Through FMI’s productivity consulting practice, we consistently see significant opportunities to improve short-interval planning skills of field managers. The same holds true for participating companies, with less than half reporting that field managers plan and communicate resource needs more than five days in advance (Fig. 4). However, based on the number of last-minute calls to the shop or daily trips to the supply house that we see in most of our clients’ operations, we feel comfortable saying that the number of field managers planning and communicating resource needs more than two or three days in advance is a very small minority.

The lack of planning skills at the field management level is a significant industry problem. If your field managers have to call your shop or make trips to the supply house on a daily basis, it is safe to assume that your crews are often waiting or delayed. In addition to the labor cost impact, buying materials and supplies at the last minute ensures you are paying a premium. Furthermore, we have learned that if field managers get the correct labor, tools, equipment, materials, and information in the crews’ hands at the right time, the result is decent productivity. Use of a practical and formal short-interval planning process is one key to achieving this goal. Knowing and communicating resource needs a week in advance greatly increases the likelihood that all resources are available when needed, which, in turn, decreases nonproductive time.

Survey results regarding daily planning and goal setting also revealed opportunities for improvement. According to our survey, an overwhelming 66% of respondents reported that less than half of their field managers use daily planning and goal setting, while 40% believe that less than one-third of field managers follow that practice.

Project Manager Impact

Project planning processes, however, are not enough on their own. An organization with well-defined processes cannot expect to deliver projects in the most productive manner without effective project managers. The best tradesmen and field managers in the industry can only do so much without proper support from project managers to provide the right materials, tools, information, equipment, and feedback at the right time.

On a scale from one to 10, 71% of PMs fell in the good, but not great, range of six to eight, which indicates there is room for improvement in the industry (Fig. 5). The real question you should ask is, “How would our field managers rate the quality of support they receive from our project managers?” Their responses may not be as flattering as those of the executives answering our survey. In high-performing companies, project managers truly understand that their primary role is to support the field.

Measurement and Feedback for ProductivityImprovement

To manage practices that lead to improved productivity, first one must measure what he or she intends to manage. When asked whether job cost reporting processes track units per labor hour, 43% of electrical contractors responded in the affirmative. While the majority of electrical respondents do track units in addition to time, that leaves nearly 60% who only report time to a cost code, leaving little of the necessary data to effectively manage the process of increasing productivity through this metric. Because productivity is defined as units per man-hour or man-hours per unit, trying to track, measure, and manage productivity without these two key pieces of data is unrealistic. To create a consistent culture around productivity, contractors need to be able to communicate clear expectations and track actual unit performance for this key metric.

Controllable Variables' Effect on Productivity

Many obstacles to productivity reside within an organization, which puts them under the control of the organization’s leadership to overcome. Overwhelmingly, respondents list planning and communication issues as the most negatively impactful internal challenges with regard to productivity, with “lack of planning skills with our field management level” as the most often selected response (Fig. 6). That said, those who reported significant productivity increases instead selected lack of communication skills at the field management level most frequently. While improving planning procedures at the field level is no silver bullet, it is the clear first step in a comprehensive process of improving productivity. Without a clearly defined, formal planning process in place, how is a construction professional able to determine the root cause of productivity problems? With such a process in place, it is far easier to start by asking whether the process was followed and, if so, to then explore what might have contributed to poor productivity.

While poor quality of plans and specs was the most frequently selected external challenge, organizations that reported significant improvements in productivity did not select this external challenge as an issue. In companies where productivity increased, there was more concern for slow responses from other project team members (Fig. 7). At the same time, there was significantly less concern for project coordination with other team members. On the other hand, unrealistic customer demands and availability of qualified field managers are top issues for these firms but are less so for the rest of respondents. While the results of this survey do not answer the question of how some firms manage external issues better than others, they do clearly indicate that internal practices can have a significant impact on potential external challenges.

Other Productivity Drivers

While simple blocking and tackling, such as better planning and communication, are essential to improving productivity, the industry is undergoing significant changes in procedures, roles, and responsibilities. Emerging technologies, methodologies, and practices, such as building information modeling (BIM), integrated project delivery (IPD) and lean construction, and prefabrication, create opportunities for increased productivity.

BIM — A review of industry news media and trend reports clearly indicates that use of BIM is continuing to grow. For those contractors answering our survey, 63% of all respondents and 81% of electrical contractors have worked on at least one project where BIM was employed. As BIM use increases, it is widely expected that its usage will enable greater collaboration across the supply chain of the construction industry. That collaboration, in turn, should also create opportunities for productivity improvement. Survey respondents support this observation, as 62% indicated improved productivity using BIM.

The most common applications of BIM, especially for electrical contractors, are clash detection, prefabrication management, and shop drawing reviews (Fig. 8). Many of these applications create the potential for significant productivity gains. For example, clash detection can save on wasteful rework by allowing clashes to be detected before equipment is installed and has to be taken out again, saving time and money. Beyond the individual applications, BIM usage allows better planning all along the process.

IPD — Integrated project delivery (IPD) is not yet employed as often as BIM, with only 43% percent of electrical contractor respondents reporting that they have worked on at least one project where IPD was used. While a minority of respondents have used IPD, the results for those who have are clear. Productivity improved at least slightly for nearly 70% of total respondents who have experience with IPD (Fig. 9). Furthermore, 19% of those total respondents who had used IPD reported that it improved productivity significantly. As news of these successes spread, along with best practices and lessons learned, it is our belief that IPD usage or some variation of a more collaborative delivery method will continue to rise. When it does, the benefits of the greater levels of planning, communication, and coordination that IPD requires will be felt in the form of improved productivity.

Lean management — Familiarity with lean management practices is high among respondents at 72% of all those surveyed. In response to the question regarding thoughts and perceptions of lean construction, 42% believe it’s nothing more than good management practices that have been relabeled. Another 27% believe it’s a practical way to improve productivity and/or operational performance. Regardless of whether or not it’s marketing spin, 69% of respondents believe the underlying practices are a great approach to increasing productivity.

While firms are very familiar with the idea and believe it’s a way to increase productivity, only 47% of electrical contractors have used formal lean management practices, tools, or techniques. It is unclear what is stopping the remaining 53%, although many respondents did report a lack of clarity around what lean management practices are or how they apply to the construction industry. Nonetheless, 80% of electrical contractor respondents that have used lean management practices report at least slight productivity gains, with 10% reporting significant productivity gains (Fig. 10). Clearly, the underlying practices, techniques, and tools of lean offer a viable opportunity for productivity improvement.

Prefabrication — Nearly 70% of survey respondents and 100% of electrical contractors currently use prefabrication as a strategy for productivity. Of those who are using prefabrication as part of a strategy for productivity, 98% estimated that it has at least some impact on productivity improvement, with 42% estimating that impact to be greater than 10%.

While many of our respondents have incorporated prefabrication into their overall productivity strategy, FMI believes there is room for further adoption across other trades in the industry. FMI’s “2010 Contractor Prefabrication Survey” reported that approximately 75% of respondents used prefabrication on less than one-fifth of their work.

One challenge highlighted in the 2010 survey is that, much like the subject of productivity as a whole, evaluating the improvements that prefabrication may bring to a firm is complicated by a lack of consistent metrics. As a result, some firms are taking a cautious approach, as they are unable to calculate the ROI of developing internal prefabrication capabilities (Fig. 11).

Concluding Thoughts

As challenged economics and depressed put-in-place statistics seem likely to remain well into 2012 and maybe beyond, contractors must cope with the reality that they must make the most of the work they are able to secure. Productivity improvement offers the greatest opportunity to increase the bottom line while top-line figures remain lower than in past years. Although a group of respondents has adopted what FMI views as productivity best practices with the result of improved productivity, it is clear that, even among those respondents, there is more room for improvement across the industry.

techniques and practices, such as BIM and IPD, offer the potential for improved productivity through greater planning, coordination, and collaboration. That said, the benefits derived from the underlying blocking and tackling of better planning and processes are achievable with or without implementing BIM or working on projects using IPD methods. Productivity improvement requires a comprehensive plan and the necessary commitment of time and resources. For the electrical contractor willing to make that commitment, however, the benefits far outweigh the investment.

Kipland is director of FMI Corp., Tampa, Fla. He can be reached at [email protected].