Imagine scaling the steps inside a wind turbine, maintaining a Disneyland Resort attraction, or working on an oil rig. With the right training and experience, electrical workers can pursue these unique types of opportunities in the electrical trade.

Today, nearly 695,000 electricians keep the power flowing to homes and businesses across America, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Not all of these electricians, however, are wiring single-family homes or powering commercial buildings. Instead, when some electrical workers entered the industry, they explored opportunities in different sectors — from the military to the line trade to the renewable energy industry. Through training and hard work, they blazed their own career paths and carved out a niche for their careers.

Unlike their brothers and sisters in the trade, they face such challenges as being deployed overseas, working at great heights, maintaining off-shore, high-voltage equipment, and staying away from rattlesnakes and the searing California sun. Even so, many of them would not trade their job for anything else in the world. Here are their stories in which they chronicle the challenges and rewards of working in their respective industries as well as reveal what it takes to work in such specialized fields.

Solar Spotlight: Johnny Garcia

Johnny Garcia was born to lead. As a foreman for Cupertino Electric, Inc. (CEI), Garcia manages solar projects for the San Jose, Calif.-based electrical contracting company. On his first solar project, he helped install medium-voltage cabling as a journeyman wireman for a Fresno County solar farm. After only a few months on the job, he was asked to help run jobs in a leadership role.

“I jumped at the chance,” Garcia says. “I’ve been a foreman ever since.”

Currently, he and his team are working on a utility-scale solar farm in the central valley of California. Garcia, who grew up in Fresno, says he enjoys managing solar projects for CEI.

“It’s awesome to get to see how the system is built from the ground up,” he says. “Because of the type of work, I get to have a hand in a little bit of everything.”

Since he was a student at Fresno City College, he says he has always loved taking things apart and seeing how they work. After taking a Code class, he worked as an apprentice electrician for his friend’s parent’s electrical shop to gain experience. After topping out as a journeyman electrician, he dove into the solar world by joining CEI. In his current role as a foreman, his job demands a significant amount of foreshadowing and the ability to stay ahead of the curve.

“You always have to have a plan — and a back-up to that plan — to keep the guys busy on the job site,” Garcia says. “One of the key skills you have to have in this job is to be able to overcome obstacles at a moment’s notice. You need to keep things moving.”

Solar projects are typically much more synchronized than commercial jobs, which often aren’t as predictable, he says.

“Solar sites are built in waves,” he says. “You do medium voltage first, then DC cabling, then piers. But, with a commercial project like a school, you can go do underground, then a rough-in in a wall, and then change to the next building. At a solar site, you know what’s coming next. Solar has a clear plan.”

On a typical day, Garcia arrives at work at 6:30 a.m. and then travels to his office, which is a job-site trailer, to set up a game plan with the general foreman on the project. During their meeting, they review what they accomplished the day before and what they want to focus on during the work day.

From 7 a.m. to 8 a.m., the team gathers for Stretch and Flex exercises and reviews the Personal Risk Assessments to identify hazards. Next, they review the Job Hazard Analysis documents and standard work instructions, which describe the plan of action to tackle the work for the day. Then, from about 8 a.m. to 9:30 a.m., Garcia tests the voltage on the panels for a quality analysis/quality control effort. Since the panels must be within 2.5% of each other, if any of the panels that have been installed failed, they must be switched out. Following a mid-morning break, when he and his team rehydrate, Garcia walks the site with another person. By conducting testing in a pair, one person can troubleshoot while the other moves ahead to keep testing.

“I get in around 10,000 steps a day,” Garcia says of a typical work day.

After eating lunch and taking a rest, he is back out on the site from about 12:40 p.m. to 3 p.m. to conduct testing. He then walks back to the trailer and downloads the results of the day’s testing efforts. Next, he puts the information into an Excel template, which identifies the circuits that failed and by how much. It also lists the level of voltage.

At 3:30 p.m., he quits for the day. While he has to drive 1.5 hours each way to the solar farm from his home in Fresno, he says working in a remote location has its advantages.

“I really like the environment at the site,” Garcia says. “On a remote solar project, you’re away from everything. There is no cell service, and we work at remote sites with a lot of nature.”

While he has seen kit foxes and birds on the solar projects, he has also encountered other more dangerous species. For that reason, he and his team have the saying: “Kick it before you pick it.”

“You must kick the item you are picking up on the site because there could be an animal beneath it,” he says. “One time, I actually had a rattlesnake come out of an item that was on the ground. Luckily, I had kicked it just before bending down. It definitely startled me.”

On a solar project, however, he can perform a diverse variety of work, which makes each day different. For example, he has worked on DC systems, stringers, MV cable, fiber and cable management. At the same time, he says one of the most challenging aspects of his job is the heat.

“Some of our solar sites are really hot, so we have to be careful to stay hydrated and look out for heat illness,” Garcia says. “Every day, we preach about hydration and using the buddy system to ensure that you’re not only taking care of yourself, but also your coworker.”

Beyond staying cool and hydrated, Garcia also strives to stay in tune with the latest solar technology, codes, and regulations. As a journeyman wireman, he must do 32 hours of “upgrade classes” every three years, so he always tries to select photovoltaic and Code classes that are relevant to his work. Through these classes, he stays up to date on changes in the solar world and helps CEI to provide clean, green electricity to its customers in California — and beyond.

Disneyland Resort Electrician: Joe Shanahan

Cars speed around a racetrack at a popular Disney California Adventure park attraction, Radiator Springs Racers. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, Joe Shanahan provides preventive maintenance to the vehicles.

“It’s very interesting the work that goes into making the vehicles do what they do,” he says. “Most guests will get into the vehicle, and they’ll ride around the attraction thinking it’s all kinds of fun. Really, these vehicles are high tech.”

For example, Shanahan and the other electricians inspect the control system, which is situated at the front of the vehicle. They ensure that the vehicle is not only operating smoothly, but also that the audio is working properly. That way, the guests can listen to safety instructions and the attraction’s show elements. During a daily inspection, Shanahan also looks at electrical contactors, switches, and buttons to ensure everything is in good working order as well as inspects the motor, which is located in the back of the vehicle.

“These are big electric motors that have a lot of energy and a lot of force,” he says. “It helps the vehicle go really fast during the attraction.”

Unlike other pieces of electrical equipment, however, the vehicles cannot be simply plugged in while they are on the racetrack. Instead, they operate like slot cars, which attach to the track to get their forward motion.

“Underneath the vehicle, we have a collector shoe, and that’s how we get electricity,” he says. “The collector shoes are attached to the bus bar. We look at those and inspect them to make sure they are OK. Without power, the vehicle is not going to go.”

To become an electrician for Disney, he says it’s important to go to trade school, the military, or aerospace training. He was trained in the U.S. Coast Guard as an electronics technician and now is part of the team within Cars Land at Disney California Adventure Park.

“I know my job brings magic to the guests because every wire that I put together or every inspection I do, I know I need to have the vehicle run well so the guests have a great experience.”

Out on an Oil Rig: Josh Anderson

After leaving college and searching for a way to make money, Josh Anderson found work as a carpenter in the residential construction industry. One day, as he was working on a job for a large industrial contractor, he discovered a new job opportunity — starting an electrical apprenticeship on an offshore platform.

The bigger paycheck and overtime bonuses lured Anderson into switching trades. During his apprenticeship as an industrial electrician, he pulled cable on offshore platforms and learned how to run conduit in refineries. He says he learned 90% of his skills on the job the hard way.

“One of my coworkers noticed my hard work ethic over time, and he asked me if I wanted to wire some land rigs when a new oil field opened up in August of 2011,” Anderson says. “I’ve been steadily employed since then, and I’ve moved around the world.”

As a rig electrician for R&J Technical Services, Anderson is now working in his home state of Texas, but he spent five years in Saudi Arabia and one month in Argentina. While in Saudi Arabia, he worked five weeks on, five weeks off, but in some cases, he had to put in some extra days.

“It was so different that I can hardly describe it,” he says. “There is a lot of outsourced labor from other countries, and as an American, I was in the extreme minority. I found it to be hot, boring, and lonesome.”

Fortunately, he could get a good Wi-Fi connection at times, which allowed him to Skype with friends and family. Today, in his current role, he works for two weeks and then can go home to Rockport, Texas, to see his family for two weeks. His hectic work and travel schedule, however, doesn’t lend itself to a family life, he says. Case in point: Anderson is on call 24/7 as a rig electrician and sometimes must work nearly around the clock to get a problem resolved.

“It’s not early to bed and early to rise,” Anderson says. “It’s 24/7. We have to get out to the rig in the heat of the moment to get the issue fixed, or it can turn into a disaster for the well and cost them a lot of money.”

In addition to the long hours, Anderson also has to face many dangers while working out on the oil rig like personal injury.

“I’ve gotten shocked, and I have to deal with fatigue due to extreme lack of sleep,” he says. “During the times that you are on the job for two or three days, you may get a nap in the truck, but that’s about it.”

Another danger is maintaining the rotating, high-voltage equipment on the rig.

“The top drive is the giant machine that grabs the pipe and does the drilling,” he says. “It doesn’t seem like it would be powered by electricity, but it has several auxiliary motors on it. The variable voltage motor can go up to 1,000A. It’s extremely deadly, and it can blow your hand off if you touch it.”

Anderson must also work at heights during his job. For example, to maintain equipment, he may need to work 100 feet off the rig floor on a 10-inch × 14-inch board with a hoist, harness, and as few tools as possible. Recently, he was up in the hoist for about 70% of a 17-hour work day.

“It’s hard on the body, feels like you’ve been beat up and on the run after a top drive call,” he says.

While on call, he often must troubleshoot damaged equipment. Oftentimes, the rig hands are not as gentle with the equipment as the electricians, and they yank the cables around, he says. In turn, Anderson must repair plugs, splice cables, and replace equipment that has failed.

“They run it into the ground and get all that they can out of it,” Anderson says. “I have to test the motor, and if it is no longer looking good, I have to get a new one and put it in.”

When he runs his service truck, he keeps it stocked with the necessary parts and equipment so that he can make these repairs swiftly. Otherwise, if he is working in a remote location, he won’t have the materials he needs to get the job done.

Since he is working in such a remote area, he must sleep near the rig. While working in an off-shore platform, he slept in a sturdy, explosion-proof trailer on the platform with the rig hands. Now that he is back in Texas, he sleeps in his own bedroom within a trailer on the property.

“While we have our own living quarters, sometimes we are out all night working so we don’t get a chance to sleep,” he says.

Working as a rig electrician may have its challenges, but Anderson says it’s also rewarding.

“It’s a good feeling to earn others’ trust and know that you are appreciated,” Anderson says. “When there’s downtime, and they’re not able to drill, I help to figure out the problem and get it fixed. It’s the best part of the job. It’s also the highest paying electrical work that you can do.”

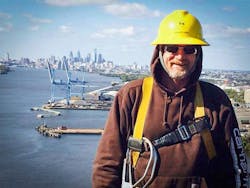

Working in the Wind Industry: Paul Inman

Paul Inman followed in his brother’s footsteps by joining Shermco Industries, where he now works as a wind turbine technician in Minneapolis/St. Paul, Minn.

“I saw how much he enjoyed his job and thought: ‘That’s the place I can build a long and enjoyable career,’” says Inman, who also worked in maintenance, retail, and banking before entering the renewable energy industry. “At the time, I had never even seen a wind tower in person, but I was excited to try something new.”

The electrical and mechanical field technicians provided Inman with hands-on, on-site training. As he progressed in his career, the electrical safety trainers continued to keep him informed on the latest safety codes and training. For example, as a wind technician and fiber-optic technician in the renewable industry, he must stay current on OSHA, MHSA, electrical safety, LOTO, confined space, test fit, DOT compliance, climb certification, driver training, tower rescue, CPR, and first aid.

In his 11 years with the company, he has performed onsite electrical motor testing, preventive maintenance on AC and DC motors, and ice blast cleaning. He has also participated in onsite bearing inspections and replacements, wind turbine generator/gearbox up tower replacements, and bearing/collector ring replacements not to mention worked on rotor leads, new tower construction, and 500kV breaker installations.

In his current role, he performs end-of-warranty gearbox inspections for a customer. Using a borescope, he inspects the gears and bearings in the gearbox to ensure there are no defects, cracks, or abnormal wear patterns.

On a typical work day, he shows up on the site about 15 to 30 minutes early to meet with the site contact. After reviewing the job scope with the customer, he attends a tailboard meeting, which focuses on possible hazards that can occur during the job. Once the electrical and mechanical technicians understand the job scope and hazards, they start inspecting and troubleshooting the machine/equipment that needs repair.

To work in his current position, he says it’s critical to know how to communicate, be flexible and adaptable, make decisions and solve problems, and have the skills to plan, organize, and prioritize work. According to Inman, the same electrical testing and troubleshooting skills he’s using on the job now for Shermco Industries could easily be transferred to the industrial field. By working on wind projects, however, he’s able to travel to different locations all over the country. At the same time, he says the most challenging part of his job is the climb to the top of the wind turbine.

“Working at 250 to 300 feet in the air can be challenging,” he says. “Space is limited, and if you forget a tool, you’re playing rock, paper, scissors with your coworker on who is going to climb down to go get it.”

Despite the challenges, Inman says he couldn’t have asked for a better line of work.

“I love my job, and cannot see myself doing anything else,” he says.

Serving His Country: Zachary Hovermill

To train for a career in the electrical trade, aspiring electricians can enroll in vo-tech programs, join an apprenticeship, or enlist in the military. Zach Hovermill opted to join the Marine Corps at the age of 20. During his enlistment, he is gaining skills and experience he can use for a future career as an electrician.

“I got selected in the Military Occupational Specialty 1141 Basic Electrician program,” Hovermill says. “I got interested in this field so I could utilize the skills I learned to transition back to civilian work after my four-year enlistment.”

Hailing from Hagerstown, Md., Hovermill is now a Corporal based at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, Calif. He also serves as a fire team leader at 7th ESB Support Company Utilities Platoon with the 1st Marine Logistics group. As a basic electrician, he works closely with the engineer equipment electrical system technicians and refrigeration air conditioning technicians.

“Over the past three years, I have been fortunate to cross train with both jobs,” Hovermill says. “This has afforded me the opportunity to perform various levels of maintenance on advanced medium mobile power source generators and military-grade environmental control units.”

While he doesn’t have any experience in the electrical field prior to joining the Marine Corps, he is learning the skills on the job. For example, two years ago, he was deployed to Iraq for six months, and was able to work closely with and learn from the civilian contractors who had a lot of experience. During his time in Iraq, he worked for the base camp commandant. He performed interior wiring and installed switches for lights, but most of his work involved fixing and installing A/C split units for life support and control areas. As he did the A/C repairs and installations, he said he had to contend with different voltages, which posed a significant challenge.

In his current role, he says he must pay attention to detail while he’s wiring up generators and working around electricity. Also, he says basic knowledge is needed to distribute power from the mobile electric power distribution system replacement panels to branch power in different locations.

A basic electrician must also stay in shape and be able to travel throughout the country or world when necessary. Each morning, he wakes up about 5 a.m. to prepare for physical training, which lasts about an hour-and-a-half. Next, he changes into his Marine uniform to start his work day.

While at work, he supervises Marines on tasks, including conducting preventive maintenance checks and services, corrective maintenance and preparation of equipment in support of I Marine Expeditionary Force. Daily, he plans field exercises, which include identifying how much power an exercise may need and how it is distributed. In addition, when equipment returns from a field exercise, he and the Marines conduct operation checks and detailed inspections to ensure the gear was properly maintained.

“My favorite thing about my job is teaching and mentoring Marines about our job in any way that I can,” he says. “One thing I wish we could improve about our job as electricians is working more with interior wiring because it is rarely used on our base structures.”

On the job, he is learning about the planning and application of distributed power. But unlike most electricians who work in the civilian world, he and the other Marines power up more remote locations such as field environments during training and deployments.

“The power is run from our generators and distributed to mobile electric power distribution system replacement panels, which act as a service panel similar to commercial and residential settings,” he says. “The distribution cables are then run into various temporary structures supplying power to computers, lights, gear, radios, and environmental control units.”

His current position also requires travel when necessary. For the most part, he and the other Marines are all stationed on one base, but they also support exercises both throughout and outside of the continental United States.

Following the completion of the basic school, he will have the opportunity to attend an advanced electrician school, which teaches more about electrical base camp support planning and interior wiring. While he has been taught about the National Electrical Code (NEC) and the Unified Facilities Criteria in his basic school house training, he is expected to stay up to date on the NEC.

“We are assisted in staying current in our certification and codes through our individual training requirements, which we practice during training and readiness events during required sustainment training intervals,” he says.

Powering America: Talmage NeSmith

Thirty-one years ago, Talmage NeSmith started his journey in the electrical trade with the Joe Wheeler Cooperative in Alabama. Since that time, he has worked for various companies all over the country.

“My job has taken me from Alabama to California and then back to the East Coast,” says NeSmith, a general foreman with The L.E. Myers Co., an MYR Group subsidiary.

In his early years, he started working as an iron worker for a welding company and a steel handler for an Alabama cooperative. Ray Alexander, a manager at his cooperative, encouraged him to enter the electrical trade.

“He described the opportunities and earning potential, and this sounded good to me,” he says. “He believed in me, which sparked my interest in the electrical trade. I was excited about opportunities to work in various locations as well as opportunities to advance my skills career in the trade.”

He enrolled in the apprenticeship program with the Local 558 union hall out of Huntsville, Ala., and completed three-and-a-half years of training while working for the co-op.

During his career, he started out by handling right-of-way clearing activities and reading meters before entering the apprenticeship program. Once he graduated, he became a journeyman lineman, and because he handled trouble calls, he was on call every day.

“I have done a bit of everything and have paid my dues,” he says.

For the last 15 years, he has worked on and off for the L.E. Myers Co., and for seven of these years, he has served as a general foreman. He says his current position is physically and mentally demanding.

“You have to be in decent physical shape because you are always lifting and climbing,” he says. “You can’t be afraid of heights, and you must be able to handle working in all types of weather. It often requires long hours, and high-voltage electrical projects take you farther away from home than if you are a commercial electrician. It hasn’t bothered me, but this can be a negative factor. Also, working long hours in extreme heat or cold can take a toll, but for me, the rewards of a job well done outweigh the negative aspects.”

To work as a general foreman, he says it’s important to not only be able to take charge, but also to be approachable so your crews feel comfortable communicating with you.

“Communication is extremely important in this role,” he says. “Failure to effectively communicate with each other can impact safety – which is crucial in this business.”

It’s critical to be experienced when it comes to safe work practices.

“You must have a keen sense of what it takes to ensure a safe working environment, and must be able to recognize, identify, and mitigate unsafe working conditions,” he says. “You must always be aware of your surroundings, and keep safety at the forefront. This takes time and practice to hone this ability.”

On an average day, he says his crews typically work six, 10-hour days, but most of the time, he works 10 to 12 hours a day, seven days a week. They start each workday with a tailboard meeting to ensure everyone understands their tasks for the day, is aware of any safety hazards, and has the correct personal protective equipment. Also, he makes sure everyone is fit for duty for the day.

“Mental distractions or physical impairments can significantly affect our safety,” he says.

To stay current in his job, he says it requires a lot of ongoing training. For example, he says he receives specialized training, and L.E. Myers ensures that he and his team have the training, resources, and tools to perform their jobs to the best of their abilities. He has undergone OSHA 10-hour and 20-hour training, and classes like First Aid and CPR are required/must be repeated on a regular basis. In addition, because he works in a management role, he must participate in leadership training — and anytime a code or electrical standard changes, he must receive training as well.

Right now, he is working on the Surrey-Skiffes Creek 500kV transmission line project in Virginia for Dominion Energy, who has been a long-term client of L.E. Myers. The project consists of constructing 4.3 miles of new 500kV transmission line on lattice tower structures across the James River and 2.3 miles on land consisting of steel monopoles with single circuit 3-1351 ACSR 45/7 “dipper” conductors. The crews are using barges for the river crossing where spans range from 1,000 feet to 2,000 feet long.

He says that although he’s looking forward to retirement, he has enjoyed working in the line trade. He says it’s especially rewarding when he has a strong crew and a job is successful.

“I’ve been able to make a nice living, and I’ve been able to work all over the country,” he says. “Being a lineman gives me a great sense of pride, especially when it comes to restoring power for communities after a storm event — like a hurricane. That’s when people really gain a sense of what we do.”

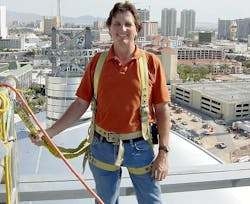

Lighting a Live Stage: Jim Holladay

As the grandson of a residential electrician, Jim Holladay grew up around the electrical trade. When he entered high school, most of his friends played in bands, and they asked him to help behind the scenes.

“I started learning how to fix guitar amps, build the electronic devices for the musicians, and do the sound and lights for the bands as well,” says Holladay, who now works as a senior project manager for Production Resource Group (PRG) LLC in Las Vegas. “I couldn’t play an instrument, so I did the lighting and audio instead.”

Fast forward to his college years, where he worked for a theater company in the summers and majored in theater. After he graduated, he started working as a stage electrician for several different companies.

“I started touring with bands in 1973,” he says. “Over the last 45 years, I have seen it change from an upstart jerry rig kind of business to the professional and organized industry that it is today.”

In the early days of his career, he went on tour with companies such as Jericho Sound, Tom Fields and Associates, and See Factor. As part of the production crew, he worked on the light and sound crew for musicians, such Neil Diamond, Billy Joel, Rush, Aerosmith, and the Blue Oyster Cult. He says touring on the road with the production crew is a “young man’s job,” but he thoroughly enjoyed the experience.

“I’m glad I did it,” he says. “Working on the rock and roll concert tours were certainly some of my best days in this business. It was hard work and required long hours, but when you got your team together, it was amazing how fast you could get a show loaded in, set up, and ready for sound check.”

Looking back on his days on the road, he remembers working from sun up to midnight to set up and tear down live shows. Typically, the bands would perform their sound check at about 3 p.m. and then practice their warmup. After the crew took a quick break, the audience would flow into the venue. Following the end of the concert, the crew would haul all the lighting and sound equipment out of the building and load it on a truck.

“We had to try to sleep on the bus with about eight to 12 other people on the way to our next gig,” he says. “Then at

6 a.m. to 8 a.m. the next morning, it would start all over again.”

In his current role at PRG, he is responsible for supervising the permanent installation of lighting, sound, and entertainment systems at various Las Vegas venues, ranging from hotels to casinos to theaters.

“I work with the creative and theatrical people and translate what they want to do to the electrical contractors,” he says. “Then, the contractor does what he needs to do to meet building and electrical codes. I go back and forth between the two worlds.”

During his career, he has worked in most of the casinos on the Las Vegas Strip. For example, his first job in Las Vegas was to illuminate the pirate battle at the Treasure Island Casino. He has also worked on the Freemont Street Experience attraction, the Cirque theaters, and the Lake of Dreams feature at the Wynn Resort.

“My favorite part is working with people to take a form of entertainment, whether it is a concert, play, or show, and make that show happen,” he says.

At the same time, he says working as a stage electrician can be challenging due to the tight time frames on certain projects. If he is working on a project to install an entertainment system at a casino, the job can last up to two years. On other jobs, he has to work on a very fast turnaround to ensure that the electricians have the designs and specs to begin and complete their work on time.

On a majority of the entertainment projects, most of the electrical work is done by licensed electricians, while he says his group handles the low-voltage work, system turn-on, system commissioning, programming, testing, and audio lighting and rigging.

“In Las Vegas, most of the electrical contractors are very well qualified and have highly skilled electricians, so we let them do as much work as they are comfortable working on,” he says. “Some of our work is very intricate, however, so we will often work on a certain part of it.”

Currently, for PRG, he supervises all the installations for his company.

“I make sure that everything is running smoothly, the electricians have what they need, and that the communication stays open between the contractors and he clients,” he says.

Over time, he has learned that it’s important for stage electricians to develop their own way of doing things.

“You have to rely on your base knowledge of what works and what doesn’t work,” he says. “You tend to set up your own internal rules as to how to go about getting power and everything connected.”

The entertainment business is always changing, so to succeed as a stage electrician, he says you must have the ability to problem solve and ensure the equipment works not only properly, but also safely.

“I think the entertainment industry is one of the greatest industries in the world,” he says. “I love seeing the audience amazed or astounded and applauding at the end of the show.”

Fischbach is a freelance writer based in Overland Park, Kan. She can be reached at [email protected].