Whitney Westerfield has just arrived in St. Paul, Minn. — a long way from his home state of Kentucky — and he sounds tired. Friendly, but tired. Over the next few days in late June, the attorney and state senator from Kentucky’s 3rd District will attend a criminal justice conference, but right now, as he settles into his hotel room, he’s preparing to talk about the electrical industry. “Where do you want to start?” he asks, with a soft, easygoing drawl.

The logical place would be at the beginning: What was Westerfield thinking in early 2018 when he introduced a bill to the state legislature that would allow prospective electricians to acquire a license without attending a single training course or passing an examination on the Code? Why did he continue to push the bill despite vocal opposition from a significant portion of the electrical industry in Kentucky? And why would a legislator who admits to knowing less than nothing about electrical wiring propose a change to the state’s licensing procedures that some believe will endanger the safety of his constituents?

The answers to those questions boil down one simple fact: Kentucky has lost electricians at an alarming rate over the past 15 years, and Westerfield wanted nothing more than to stem the tide. Whether or not his solution was appropriate is still up for debate in Kentucky — and that debate may spread across the country if other states attempt to address their own skilled labor shortages with similar legislation.

A Test of Wills

Senate Bill 78, which called for the creation of a one-year, nonrenewable provisional license, was introduced Jan. 11, 2018. But its story starts a decade earlier, in Hopkinsville, a town of some 31,000 people located in the southwest corner of Kentucky.

By 2008, Mark Gary had been in the electrical business for more than 35 years. His shop, Holland Electric, had a small crew of three licensed electricians and three unlicensed techs who he desperately wanted to get licensed. Problem was, they couldn’t pass the state examination, despite, in Gary’s opinion, having the requisite skills to be full-fledged electricians. And no amount of encouragement, motivation, or haranguing could help them get over the hump. “Some people just freeze up when they take a test,” Gary says. “But if you give them a set of plans, they know exactly what to do.”

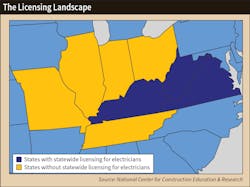

Licensing for electricians was still a fairly novel concept in Kentucky’s neck of the woods in 2008. Of the seven states that surround it, only two require a journeyman’s license to this day (see Map). Kentucky’s program, which established separate licenses for contractors, master electricians, and electricians, only came into being in 2003. Those who could prove they had four years of experience in the trade prior to the law’s passage were grandfathered in and automatically received the electrician’s license. At the time, just north of 21,000 electricians and master electricians were grandfathered in. Anyone who didn’t meet that requirement would need to accrue four years of experience, attend a state-accepted training program, and pass an NEC proficiency exam.

Gary’s techs weren’t the only ones struggling to pass that exam, by the way. Administered by the Minnesota-based testing firm Pearson VUE, it’s a four-hour, 80-question, multiple-choice test. And despite being open-book, just 45% of applicants pass it on the first try, according to numbers provided to EC&M by Kentucky’s Department of Housing Buildings & Construction, which oversees electrical licensing. Second-time test-takers don’t fare much better: Only 47% pass.

At the same time, established electricians have been leaving the trade in droves, as evidenced by a precipitous drop in licensed electricians in the time since the state’s licensing law was passed in 2003. As of July 2018, just 11,199 journeymen and masters remained. In other words, Kentucky has experienced the same skilled labor drain the rest of the country has been feeling, but it’s been compounded by the fact that those people who actually want to be electricians are struggling to break into the industry.

With no reason to believe his techs were going to become expert test-takers any time soon, Gary turned to his state senator, Joey Pendleton, for help. The two talked at length about legislative options for amending the licensing requirements, but nothing stuck, and Pendleton served another term without introducing a single bill to address Gary’s concern.

Gary’s luck turned in the fall of 2012, with the election of Whitney Westerfield. Like his predecessor for the 3rd District senate seat, Westerfield was from Hopkinsville. He even attended the same church as Gary. Unlike Pendleton, however, he was a Republican, which instantly gave any of his bills a leg up in the GOP-controlled senate.

Westerfield was sympathetic to the predicament that both Gary and the industry faced. The more he asked around, the more he thought something needed to be done. “When I brought it up to other legislators that are in this sort of policy world they said, ‘Yeah, this is a real thing. Thanks for noticing,’” Westerfield says.

In 2014 he introduced a bill that would make the state responsible for developing and administering a new exam, as well as hosting a class to prepare applicants for the exam. It failed to make it out of committee. He tried again in 2016 with an almost identical bill that suffered an almost identical fate. So, for all intents and purposes, his attempt to give Kentucky’s electrical industry the shot in the arm it so desperately needed was dead in the water.

If at First You Don’t Succeed

What if there was another way, Gary thought, a way that wouldn’t require making any changes to the exam? What if it were possible to ease the licensing requirements — at least temporarily — to encourage more people to get into the industry? What if men and women who’d shown a good faith effort to learn the trade could apply for a provisional license that allowed them to work as electricians for a limited amount of time and build up their skills — and more important, their confidence — to take the exam?

“We looked at it as an incentive, a way to give a sense of what it’s like to have a license and be entrusted with it,” Westerfield says. “If it provides just a little bit of extra oomph for people who are going to sit for that exam to study harder, to work harder to get ready, then it’s worth a shot.”

At the beginning of the 2018 legislative session, he introduced Senate Bill 78. Not just anyone would be eligible for the provisional license, though. Applicants had to be Kentucky residents and prove they had six years of experience in the trade, for 2,080 hours per year. The license would be good for just two years and, most important, nonrenewable.

As far as the senator from the 3rd District was concerned, the provisional license was their best shot, in large part because it arose from a meeting in Hopkinsville the previous summer between himself, Gary, and a handful of representatives of the IEC of Kentucky and Southern Indiana.

Erv Klein was one of those in attendance. A one-time HVAC contractor and current lobbyist for the IEC, he wasn’t exactly crazy about the idea of messing with Kentucky’s licensing requirements. In fact, he thought they were just fine the way they were. But he couldn’t deny that the state’s electrical industry was facing an ongoing shortage, so he was willing to at least come to Hopkinsville and hear Westerfield and Gary out. “They’d devoted a lot of time to trying to come up with solutions,” Klein says. “We were taking them at face value when they said they wanted to attract more qualified people to the industry.”

Rather than create a provisional license, though, Klein and the other IEC representatives suggested increasing access to training. Kentucky is a predominantly rural state; according to the U.S. Census Bureau, nearly 45% of its population lives in rural areas, compared to just 19% nationwide. If the organization could get more people enrolled in electrical education programs, whether online or in person, Klein argued, it could begin to make a dent in the electrician shortage. He even went so far as to offer opening an IEC training program right there in Hopkinsville, provided Westerfield and Gary could find a location for it.

That was all fine and good, Gary said, but he needed more immediate help. If the IEC would support the provisional license, they could talk about starting the training program later. When he and the rest of IEC’s representatives left the meeting and began the two-and-a-half-hour drive back to their offices in Louisville, Klein believed some progress had been made. The provisional license wasn’t ideal, but it was a compromise he could live with. Others in the industry were not nearly as accepting.

All Charged Up

“What was done with this piece of legislation was a travesty,” says Steve Willinghurst. “We were the last trade in this state to get licensing, and it seems like it’s been under attack ever since.”

Willinghurst is a second-generation electrician and the director of education and training for the Joint Apprenticeship and Training Committee (JATC) in Louisville. He was also a vocal opponent of each of Westerfield’s bills, including the first two that would have created a new exam. “It’s an open-book test,” he says. “It’s not that hard if you’re prepared and know how to use the Code book.”

In fact, while he will acknowledge that the electrical industry is experiencing a skilled labor shortage, he — somewhat paradoxically — disputes the notion that there’s been a decline in interest in the trades. And he offers as proof the 753 applications he says the Louisville JATC program received over a six-and-a-half-day period this spring. He also disputes the state’s numbers that show there are less licensed electricians in Kentucky today than there were 15 years ago, though he won’t elaborate how he came to that conclusion other than to say he “went a different direction on it.”

Anyone who is having trouble hiring, he says, just isn’t offering adequate training or paying their employees enough. It’s worth noting here that the median hourly wage for Kentucky electricians has increased by 32% since the licensing law was passed in 2003 (see Chart). In other words, from Willinghurst’s perspective, there was no need to do anything to solve the problem because there was no problem to solve.

It should come as no surprise, then, that for him, the idea that someone could get a license to wire anything — whether a hospital, home, or barn — without attending a training program or passing an exam is a nonstarter. And he made his opinion heard when he testified in front of the legislature in early 2018. “You’re going to have less qualified people out there doing work under the guise of having an electrical license,” Willinghurst says now. “And the consumer is not going to know the difference.”

Sal Santoro heard testimony from the bill’s opponents like Willinghurst. He’s a Kentucky state representative from District 60, near the Kentucky-Ohio border, and he sits on the Committee on Licensing, Occupations, and Administrative Regulations. He’s also the owner of Santoro Electric Co. Inc., a contracting firm that’s specialized in commercial and industrial work for three decades.

Santoro’s district is just south of Cincinnati, which happens to be in the middle of a construction boom. As the cost of living has increased north of the border, Ohioans have begun moving south to Kentucky, and Santoro can’t keep up with the work they’re creating. “There’s just so much going on in northern Kentucky, I could hire two people today,” he says. “But there just aren’t enough licensed personnel to fill what we need.”

Although a potential conflict of interest prevented him from co-sponsoring Westerfield’s bill, Santoro supported it. (He will admit to lobbying on its behalf “behind the scenes.”) And the main reason he wasn’t concerned that the creation of a provisional license would hurt the quality and safety of electrical installations across Kentucky? “At the end of the day,” he says, “that work still has to pass inspection. It has to be reviewed by a state inspector.”

Westerfield takes that argument a step further: A license — provisional or otherwise — doesn’t guarantee anyone a job. “Whether an electrician has the minimum amount of experience or 30 years of experience, the owner of the business who gives that goober a job is responsible for what that goober does,” he says. “And that’s not going to change, no matter what standards we create.”

A Path Forward

Disagreements over how the provisional license would affect Kentucky’s electrical industry aside, Westerfield says he tried to take as much of the input he received from all stakeholders and incorporate it into the bill. For instance, an early draft of the bill made no mention of whether applicants had to be Kentucky residents. So, as representatives of the IBEW pointed out, electricians from any one of the seven states that neighbor Kentucky could cross the border, get a provisional license, and take work that would have otherwise gone to a local. So Westerfield added a line requiring Kentucky residency.

When the IBEW pushed back on the length of the provisional license — arguing that while any length of time was unacceptable, two years was wildly excessive — Westerfield reduced it to one year. (Willinghurst, the JATC training director, doesn’t believe his concerns were heard “by anybody that was on that side of the fence. Their minds were already made up.”)

Still, the bill was far from a slam dunk. It sailed through the senate within two weeks of its introduction, passing by a 26-10 vote, but then languished in the house for two and a half months. When it finally came up for a vote on April 14, the last day of the legislative session, it passed — by a single vote. As of July 14, 2018, the Department of Housing Buildings & Construction was cleared to begin issuing provisional licenses.

As he discusses the resolution of Kentucky’s provisional license saga, Mark Gary does not sound like a man who’d just emerged victorious from a nearly 10-year fight. Instead, he chooses his words very carefully, making a point to say that through all of this, his number one concern was looking out for low-income families who he believes would have been in danger of paying exorbitantly high prices for simple electrical work had the number of licensed electricians continued to dwindle. “I don’t want to see the residents of Kentucky be taken advantage of,” he says.

And that training center that he and Erv Klein had discussed putting in Hopkinsville to increase access to training? The talks are still ongoing.

For his part, Westerfield has moved on to other things. At the moment, he’s in the midst of campaigning to be Kentucky’s next state attorney general. If that falls through, he’ll be back in the senate to finish out the last three years of his term — where he’ll keep his eye on the effects of the provisional license. He won’t say how long it will take to know whether it’s been good or bad for the state’s electricians, but either way, he’ll be ready to make a change, if necessary. “If it’s been positive, great. Let’s expand on it,” he says. “If it’s been negative, let’s revisit it and undo it, or fix what’s gone wrong.”

Halverson is a freelance writer based in Seattle. He can be reached at [email protected].