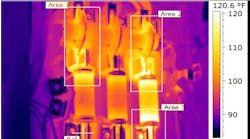

In a recent in-house safety survey, 65% of industry respondents agreed that they use tools “properly rated” for the jobs they're performing. But what about the other 35%? Electricity is not a power to play with. If tools are underrated for the job, they can damage equipment, cause arc flash, explode, or deliver deadly blows to the user (and potentially those in the vicinity), as demonstrated in Fig. 1. How do you know if you have the right meter for the job? Let’s examine this further.

A well-built meter will protect you against electrocution and arc explosion. It will carry a Category rating as well as third-party certification by an independent test laboratory. If the meter isn’t properly rated and certified, there is no way to tell if it offers the necessary protection against electrical transients that may lead to insulation breakdown or arc explosion.

The Switzerland-based International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 61010 establishes measurement categories (CAT) and voltage ratings for electrical environments. The system establishes categories to provide guidance to help protect you from the increased risks of making live measurements when testing or troubleshooting the power system. With CAT environments II, III, and IV, the available fault current in these high-energy circuits can reach as much as 100kVA (see Fig. 2).

CAT rating descriptions

A high CAT number refers to an electrical power system with higher power available and higher energy transients. Essentially, the higher the short-circuit fault current available, the higher the category. This is a key principle to understand when it comes to choosing and using test instruments. A test instrument designed to the CAT III standard can resist much higher energy transients than one designed to CAT II standards. Transients are dampened by system impedance as they travel from the point where they were generated.

CAT IV refers to the “origin of installation,” or where the connection is made to utility power or measurements on devices installed before the main fuse or circuit breaker in the building installation. Examples include electricity meters, primary overcurrent protection equipment, outside and service entrances, service drop from pole to building, the run between the meter and the panel, and overhead lines to detached buildings or underground lines to a well pump.

CAT III refers to 3-phase distribution including single-phase commercial lighting. Examples for this environment include measurements on distribution boards, circuit breakers, and wiring, which include cables, bus bars, junction boxes, switches, and socket outlets in the fixed installation. Equipment in fixed installations may (such as solar plants) include switchgear and polyphase motors, bus and feeders in industrial plants, feeders and short branch circuits, distribution panel devices, lighting systems in larger buildings, and appliance outlets with short connections to the service entrance.

CAT II refers to single-phase receptacle-connected loads. This includes the main circuits of household appliances, portable tools, and similar loads — outlets and long-branch circuits more than 10 m or 30 ft from a CAT III source, and outlets more than 20 m or 60 ft from a CAT IV source.

Ingress protection code descriptions

Ingress protection (IP) codes are classifications associated with IEC 60529, a guideline that defines to what degree of protection mechanical casings and electrical enclosures must protect the inner equipment against intrusion, dust, accidental contact, and water. These are especially useful in protecting users and equipment in volatile or harsh environments and should be considered in addition to CAT ratings when selecting the right meter for the job.

The IP code is represented by two digits that, together, tell you what level of resistance to dust and water your meter can withstand. It details what size of dust particles will be kept out and to what water depth your meter can be submerged and continue functioning.

The first digit relates to solids and the second to water (see Table 1 and Table 2 below).

Certifications

Sean Silvey is a product application specialist with Fluke Corp. His focus is on application awareness, product education, and worker safety. Prior to joining Fluke, Sean was a field service manager in the HVAC industry for 15 years, training and supporting field service technicians as well as assisting customers in resolving HVAC issues. He can be reached at [email protected].