There’s a great lesson in an old story from the annals of software development. After Microsoft released Word 6.0 (long, long ago, in a galaxy far, far away), the company polled a large number of users on which features they’d like to see added to the next version of Microsoft Word. After tallying up the responses, they found that almost every “please add this” feature identified by existing users was already in Word.

Now, why do you think that happened? Whatever reasons come to mind for you will probably apply to test equipment used in your maintenance department (or electrical services firm).

Try polling your electricians on individual pieces of test equipment they use often, such as a high-end DMM. Ask them what type of measurement they wish it could do. This may lead to some insight, after you compare their answers with what you find in the instrument’s operating manual. You’ll get even more insight if you ask them why they want those features and aren’t using them now.

You can use this insight to plan the training needed for fully utilizing all that untapped measurement capability. Yet with some types of equipment, you can skip past the polling and go right to scheduling the training.

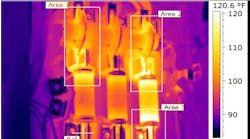

That is the case with, for example, thermographic cameras. Yes, a sharp tech can use one of today’s amazingly user-friendly cameras to get useful maintenance or troubleshooting information after spending only a little time with the manual. But there are very good reasons why the different levels of thermographer certification exist. It’s not that the equipment itself is a mystery, it’s that using it efficiently and correctly for the kinds of issues you’ll run into requires an understanding you don’t just “pick up” on your own.

Back to our polling. If you really want some eye-opening responses, ask what kinds of measurements they should be making and look for what the electricians don’t tell you.

However, the odds are that you don’t know what to look for in that empty space. The answer is going to depend upon the type of equipment you install, test, and/or maintain and the types of problems encountered with that equipment and with the environment it’s in. You can start making a list by consulting these resources:

- Manufacturer’s documentation on installation, startup testing, and recommended maintenance.

- Manufacturer’s bulletins and guides on troubleshooting.

- The applicable IEEE and ANSI standards.

- Books particular to solving specific problems in your environment (e.g., a book on solving harmonics if you have high harmonics); these will probably give you the best overall information.

- Discussions at industry conferences (e.g., “Yeah, we tracked that down at our facility by comparing RMS to averaging”).

It’s worth noting that these are among the resources used by a qualified electrical testing firm. Obviously, you can’t ask such a firm to teach your people to make that firm unnecessary. But you can ask the firm to review your ongoing (non-outage) testing procedures for the type of data you should be collecting and trending.

You may find that your equipment doesn’t have the required capability, and then you’re left with deciding whether to spend maybe $1,000 to fill that gap or form a committee to come up with a good excuse for why you didn’t see that $800,000 unplanned shutdown coming.

You can also ask the firm to conduct training on advanced testing procedures that can be used in troubleshooting the kinds of problems your maintenance and repair logs show you’ve been having. Or they can compare your testing data with their historical findings at other facilities to determine what training and test equipment you need.

For example, you get too many insulation failures. The testing firm compares your rate of conductor insulation failures with those at facilities with equipment fairly similar to your own. They find your failure rate is far greater than typical. They also are made aware that you frequently have to send motors out for rewind.

This sounds like a power quality problem. You’ve got recording DMMs, but haven’t recorded any transients. So how is the insulation being damaged? Well, the DMM isn’t the correct tool to be using to chase this problem.

Let’s say you have a harmonics analyzer. Like the DMM, it can help but cannot provide complete power quality information. But even using the information it does have means you must know quite a bit about the meter and about harmonics theory. Do you know how to interpret the findings? Can you look at the fifth harmonic and third harmonic relative to the fundamental and identify any particular suspects? How does the THD relate to your problem?

A power quality expert might tell you that finding the solution requires a power analyzer. What’s left out of that statement is that finding the solution also requires power quality expertise. And anyone collecting data for the power quality expert to interpret should be properly trained in all aspects of using the instrument.

Let’s revisit the question posed in the title of this piece. It’s really not a matter of whether your testing equipment is useful. It’s a matter of whether you are making the most useful measurements for the work you’re doing. Whether that’s installation, baseline maintenance testing, ongoing maintenance testing, or troubleshooting, you need to know:

- Which tests to perform (and why).

- What test equipment is needed to perform the tests?

- How to perform the tests per industry practices.

- How to interpret and apply the test results.

With proper training, you can have all of the above. But start with that first bullet point. Everything else proceeds from there.