Have you ever worked at a place where the best guy in your department made a buck or two more per hour than anyone else, but management laid him off to save money? How did that turn out?

It seems that “out of touch with reality” managers can find shortsighted “cost savings” efforts under one rock or another. Here a few more examples of short-sighted moves:

- “Deferring” maintenance. This gem of an idea assumes you can suspend the laws of physics just by moving calendar dates. The reality is you can’t, and this approach invariably replaces low-cost maintenance with high-cost repair. Or worse.

- “Trimming” the safety training program to “free up resources.” The logic here appears to be that when someone is injured or killed because of poor safety training, you’ll somehow have more of the workforce available. In other words, 25-1= 26. Your average third grader might challenge this kind of math, and that’s probably a good thing.

- “Making do” with old test equipment. If an investment of a few hundred dollars saves you several thousand dollars in labor (or callbacks), how exactly does not making the purchase save you money? Is it the same “justification” for not spending a few hundred dollars so you can prevent a six-figure downtime incident? Does someone at your company think that if your competitors can lower their costs through better technology, you can lower yours by not having that technology?

Yes, we all get exasperated with these expensive decisions. So why are they made? You might suspect it’s because some management folks have been eating the wrong kind of mushrooms. But the real reason is actually something else.

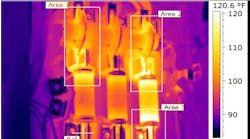

These decisions get made based on the best information available at the time. Sure, you know that installing an infrared window makes the job safer and far more efficient while making predictive maintenance much more viable. But if the person who must sign off on the purchase request doesn’t know that, what’s the likely outcome? Lacking a real understanding of what this window is and what its benefits are, the decision-maker may develop the wrong cost-benefit number and say no.

Let’s go back to that best guy in the department scenario. Has the plant engineer (or project manager) ever highlighted to higher management what particular employees have done for the company? If some people do outstanding work, but management isn’t informed, everyone becomes an undifferentiated unit of hourly labor cost. That’s how you lose your ace technicians and star electricians. This dynamic applies almost universally.

It’s not that the folks making these bad decisions are stupid. It’s that they are working with the information they have available. If you don’t provide them with the information needed to make good decisions, then bad decisions are likely to occur.

Now, think about the concept of “deferred” maintenance. A properly developed maintenance schedule correctly balances maintenance resources against downtime risk. For example, you perform insulation resistance testing on feeder cables during the annual shutdown and trend the results. Instead of saving money, skipping a year can mean you miss the predictive break in the trending curve. When a ground fault causes a fire, how does that save money? But the non-technical manager who decreed the deferment had no idea this would happen. Think about why.

The problem of saving money at great cost is, at its core, a problem of poor communication. This problem will never fix itself. And unlike wine or cheese, it won’t get better with age.

Sure, you’re frustrated with these “idiotic assumptions” made by this or that manager or bean counter. But if you’re not helping to give these folks a clear picture why an expenditure actually saves money (and why not making the expenditure costs more than what you save), you’re making an assumption, too. You’re assuming they know what you know, even though your educational backgrounds, training, and daily experiences are very different.

The bean counter back at the corporate office isn’t donning PPE, taking covers off cabinets, and performing thermographic surveys. How can that person possibly grasp from a short description that it makes sense to spend $600 on the infrared window you requested. How can this person possibly understand that this window may pay for itself the first time out by eliminating $600 worth of labor and safety costs for that particular task at that particular location?

Set aside your assumption that “they should know,” and make sure they do know. In any well-run organization, every proposed expenditure has to pass a cost-benefit analysis (among other things). That is also often true of existing costs, such as high-value employees who have received merit raises and now look like a juicy target for “cost reduction.”

If you explain and quantify the benefits, you will help managers save money for real, instead of (quite unintentionally) saving money at great cost.