Errors in grounding and bonding often produce conditions that are hazardous to people and equipment. These errors may go undetected for years. It’s the unfortunate event, such as a nasty shock or the same “mysterious” failure repeating in a piece of equipment that triggers calling in an expert who ultimately identifies grounding and bonding errors that caused the event.

What normally doesn’t go into that expert’s report is that, during all of these years, these errors have been wasting energy. The waste can be substantial.

The most common error is a grounding connection used where a bonding connection is actually required. An example of this misapplication is an industrial motor with a “grounded” housing. You’ll see a ground rod driven into the cement, with a conductor running from it to the motor housing. This does put another circuit in parallel with the motor case, but this circuit’s impedance means it can still leave a huge difference of potential between the motor housing and the supply transformer.

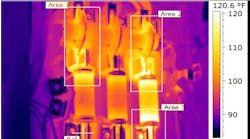

So current will flow through the motor bearings as it attempts to get back to its source (the transformer). If a skilled thermographer does a thermographic assessment on this motor, the thermographer will show very clearly that this motor has excess heat in its bearings (and probably in its windings). This can be shown in both absolute temperature terms (e.g., 190°F) and in the relative temperatures along the body of the housing (e.g., much hotter at the bearings).

You’ll find the bonding requirements in NEC Art. 250, Part V. In essence, these consist of bringing non-current carrying metallic objects to the same potential by connecting them with a metallic path of adequate size. This path is a very low resistance path.

Grounding, on the other hand, is a matter of creating a conducting connection between an object and the earth [Art. 100] or a conducting body serving in place of the earth. You can take soil resistivity measurements all day long, but you aren’t going to find a stretch of dirt that provides conductivity on par with that of a No.4 copper conductor.

Bottom line: on the load side, bond instead of ground.