Following the birth of their new baby, a young couple seemed to have it made. Living in a condominium, which was part of a 100-unit complex (built in the early 2000s) in a “bedroom” community located just outside of a major city, the husband commuted to work each morning. After using up her maternity leave, the wife made a deal with her employer: She would come into the office occasionally but spend the majority of her time working at home. The arrangement was good for one year with a chance of renewal. Working at home was great for the family, until things took an unexpected turn.

The scene

The condo featured two floors and a basement, which was converted into an “in-law” suite for the woman’s father (who also lived there). On the second floor were three bedrooms. At one end of the hall lay the nursery; at the other was a spare bedroom converted into a computer room. Not only did this space contain the family’s personal computer and peripherals, but it also housed a high-end computer and color printer on loan from the woman’s employer.

The accident

On the morning of the incident, everything seemed routine. The woman’s husband left for work, her father was in his suite, the baby was sleeping in the nursery, and she had settled into her workspace. Because she had a baby monitor hooked up to the computer, she could conveniently see and hear her baby while she worked. About mid-morning, the woman came downstairs for coffee. But before she could take the first sip, she saw smoke billowing down the stairs. Immediately running upstairs, she saw flames coming from the computer room. Grabbing her baby and running from the house, she banged on the basement door until her father fled the premises too.

They called the fire department, which responded in 5 minutes and promptly put out the fire. Although the computer room was trashed, the remainder of the condo appeared to be fine, except for some minor smoke damage. Because this condo butted up against two other units, they were examined as well and found to be completely free of any intrusion by the fire. As a result, the fire marshal rated this accident a “small” fire. However, without the woman’s rapid response, there could have been serious property damage and possible loss of life.

The aftermath

Listing the origin of the fire as the spare bedroom (aka, the computer room), the fire marshal deemed the fire to be electrical in origin. Arson was quickly ruled out, no one in the house was a smoker, and there was no evidence of paint, gasoline, or flammable material being used for any in-house project. Although he clearly suspected an electrical culprit, speculating that one of the appliances in the computer room had overheated, the fire marshal could not pinpoint the exact cause of the fire.

Because the fire was small, it took less than 48 hours before the family was allowed back into their condo. The insurance company investigated and corroborated the fire marshal’s report, paying the family insurance money needed to rebuild.

The investigation

Initially, in the first phase of the investigation, the insurance company issued a legal intent to sue the companies that sold all of the appliances present in the computer room before the fire. Pending an investigation of all of the appliances, it delivered a solid lawsuit against the company or companies whose equipment caused the fire. We were hired by one of these companies to investigate the appliances recovered from the fire. This was the first of three planned investigations.

This first investigation was held in a warehouse off-site from the fire location. Additional experts were hired by the other companies, including those representing the computer, router, printer, and baby monitor equipment manufacturers. Some of the companies chose not to participate; opting instead to wait until they were formally named in the lawsuit. This included the manufacturer of two incandescent lamps and two manufacturers of the two multi-outlet power strips that were used to distribute electricity from the wall outlet to the various appliances. The initial investigation consisted of three parts.

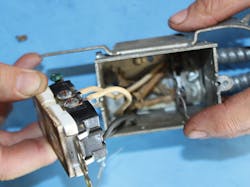

Part 1 — First, an identification was made of each appliance and its wires. Note: Many of the wires and cables were melted/burned in such a fashion that they essentially became one charred cable. It took a great deal of patience to separate these wires into their constituent parts and identify the appliance to which they belonged (Photo 1).

A curious incident occurred during this process. One of the two desktop computers appeared to be made by a very well-known American manufacturer. During the course of the investigation, however, it was noticed that the name tag was falling off due to fire damage. The tag was removed, and put in a bag for storage. But under the tag, another was discovered (made by a company in Southeast Asia). Further investigation corroborated the fact that the American company did not make the computer, nor did it outsource the computer’s manufacture. The computer was actually a knockoff with a false tag placed over the real one. Therefore, the American company was removed from the pending lawsuit and replaced with the counterfeit manufacturer.

Part 2 — The second step in the investigation was to check each appliance to see if it could have possibly started the fire. The computer with the false name tag, for example, had char and smoke damage, but when it was powered up, it appeared to be running in some fashion. Furthermore, its power supply gave proper readings and was warm but not hot. This rudimentary check suggested that it was not the origin of the fire. The baby monitor was a black blob of melted plastic. However, when this piece of equipment was opened, the inside appeared free of fire damage. In other words, it burned and melted from an external flame source; it did not start the fire. All of the other appliances were eliminated in a similar fashion.

A fire ignites when paper or wood is exposed to a temperature of 451°F. Most popular plastics ignite at 700°F to 800°F. Temperatures this high can be obtained in one of two ways. Run an appliance at a much larger current than it’s rated. (In this case, the appliance produced more heat than it could safely dissipate, which raised the surrounding temperature.) Another way to achieve ignition temperature is to run an appliance at its proper current, and allow it to produce the heat that it can safely dissipate but somehow block its ability to dissipate this heat. For example, if the heating vents of an appliance are butted up against a wallboard, the heat can transfer to the wallboard instead of into the air.

Part 3 — During the third part of the initial investigation, experts theorized what might have caused the fire. However, none could point to a clear cause. They could only eliminate products they believed were not the cause of the fire.

The second phase of the investigation consisted of a site visit to the condo. None of the other experts decided to attend this second investigation because all of the appliances had been removed from the room where the fire occurred, along with most of the large pieces of combustible material (such as a part of a table and piece of the rug). They saw little benefit to walking through a room full of debris of unknown origin. We were the only investigators that chose to attend — a decision that turned out to be a good one on our part.

At first, we were frustrated, scanning a sea of char made up of burned tables, rugs, chairs, and other combustibles. Nothing of value that might help our investigation appeared to be there — until we noticed two grounding-type receptacles in the room. The fire damage centered preferentially around one of these outlets.

Upon closer examination of this receptacle, we noticed it was fed by a 2-wire cable — an ungrounded conductor (i.e., hot wire) and the neutral conductor. Both the black/white wires (hot/neutral) were connected to the receptacle when we examined them (Photo 2). A ground wire was not seen anywhere in the cable jacket, though we did find a bare jumper wire between the outlet box and the metal cable jacket. The ground screw (green screw) on the receptacle was tight — as if it had just come from the electrical supply house. Prior to photographing it, we loosened the green screw and examined it for damage. With no wire ever connected to the green screw, the outlet presented the homeowner a ground pin that was never connected to anything.

It is well known that the NEC requires a ground wire to be present where a grounding-type receptacle is installed. What we found was a clear violation of NEC requirements. Why was their no ground wire connected to this grounding-type receptacle? Did it burn up in the fire? Was it never there in the first place? A quick check of the second grounding-type receptacle in the room revealed the same situation. All of the condo units in the complex were eventually found to be in the same state.

Note: During some of our investigations, we have found that installers will run a small jumper wire from the ground screw on the receptacle to a ground screw in the metal outlet box. The assumption is made that the metal box provides a good ground. This is not true. In the best case, the metal box does connect to a system ground via a ground wire that runs back to the panelboard. In the worst case, the metal box has absolutely no connection to ground. For all practical purposes, this creates an open circuit between the box and ground.

The outcome

We reported these findings to our client, placing them into discovery for all participants in the case to read and review. Following this submission, many additional activities transpired.

• First, there was a third investigation planned off-site in order to again view the appliances retrieved from the fire. However, before this meeting could take place, it was postponed indefinitely.

• The threatened lawsuit by the insurance company against the appliance manufacturers was withdrawn.

• The insurance company that paid out a claim for the fire damage drafted a new lawsuit against the electrical contractor who had been hired to install all of the electrical wiring when the condo complex was first built. Not only did he violate the NEC and the town’s building codes, but the billing paperwork also specified installation of grounding-type receptacles.

• After a spot check of grounding-type receptacles in other condo units revealed the same situation (i.e., lack of a ground wire), the condo board also filed a lawsuit against the electrical contractor.

• The condo board hired a new electrical contractor to fix this wiring deficiency in all of the condo units. The board simply wanted the first contractor to pay the second contractor to finish the original job he was hired to do.

• The state in which this fire took place was considering filing criminal charges against the electrical contractor. At this point in time, however, we are not privy to the status of such charges.

• As of this writing, there are no further developments in the case, but a settlement is expected at some point.

Lesson learned

Normally, when someone mentions a ground wire in an accident, the assumption is that a person was electrocuted or shocked. Fortunately, no one was injured in this case.

Our experience has shown that a leakage current as low as 2A can ignite a fire, depending on the conditions in which the appliance is operating and the nearby combustible materials (wood or paper or plastic) present. In fact, some cases of electrical fires have shown us evidence that the leakage was as high as 7A. However, these values of current are too low to trip a typical residential-type circuit breaker. This means the ground wire becomes the sole means of protection. In this particular case, we suspect that leakage current was responsible for the fire. But without further testing, we could not confirm this hypothesis. Because there was a clear violation of the NEC in the wiring of the wall outlets, we were not called in to further investigate this issue or analyze any other appliance involved in this fire.

Hmurcik is a consultant at Lawrence V. Hmurcik LLC. He can be reached at [email protected]. Patel is currently a freelance consultant and instructor at the University of Bridgeport. He can be reached at [email protected].