Health care has arguably seen more change in recent years than almost any other industry. Whether related to delivery systems, reimbursement policies, construction practices, or design trends, these changes significantly impact the way health care facilities are designed, operated, and maintained. As a critical system of these operations, the recommended practices for how these facilities should be lighted have also been changed accordingly. The official reference for these guidelines is the document published by the Illuminating Engineering Society (IES) and approved by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI). RP-29: Recommended Practice for Lighting Health Care Facilities was last published in 2006, and has now been overhauled to reflect a more current view of the lighting, health care, and building industries.

About the New Revision

Since 2006, a growing concern for health, well-being, and overall sustainability has driven changes in building design goals. LEED has progressed from version 2.0 to version 4 with LEED for Health Care introduced in 2011, which mandates an integrated design process as a prerequisite for health care facilities. Energy codes have become increasingly strict, and more projects are driven by a goal of zero net energy. In 2014, the WELL Building Standard was introduced, which emphasizes health and well-being of building occupants. The number of outpatient facilities is growing with an increased focus on preventive care.

In 2006, we saw the implementation of a patient experience survey called HCAHPS, or the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Health Care Providers and Systems, which is used to determine the reimbursement amount a hospital will receive for delivering its services. A full 2% of the Medicare reimbursement of hospitals is now at risk, pending how they score on their HCAHPS evaluations.

Lighting has the unique ability to significantly impact not only energy consumption and critical task performance in health care facilities, but there is also a growing body of evidence that shows its link to other health aspects. The health and well-being of patients, staff, and visitors, as well as their overall mood and experience, can be greatly impacted by how the lighting of these spaces is designed. Achieving these complex goals efficiently and effectively requires thorough and shared understanding by the entire design team throughout the specification process.

The 2016 revision of the ANSI/IES RP-29 document is intended to be used by a broad audience, not just by lighting designers, and should enable better collaboration throughout the integrated design team. To facilitate this collaboration, the language and organization was structured to mirror the Facility Guidelines Institute (FGI) Guidelines for Design and Construction for hospitals, outpatient facilities, and residential health care and support facilities, which references both ANSI/IES RP-29 Lighting for Hospitals and Health Care Facilities, and ANSI/IES RP-28 Lighting and the Visual Environment for Seniors and the Low Vision Population. The FGI offers guidance for the planning, design, construction, and commissioning process and facility requirements for all types of health care facilities, and is a primary resource for architects working in health care. Categorization and terminology were kept consistent to make cross-referencing between documents easier.

RP-29-16 is intended to offer guidance, not prescriptive instruction, for building and designing health care facilities. It strives to raise awareness of business, design, and technical issues that should be considered during the process, while still allowing creative freedom and customization to meet the project goals.

The Structure of the Recommended Practices Document

The RP-29 document begins with a brief introduction and then moves to a discussion of the design considerations that should be followed with health care projects. The introduction reviews the types of facilities addressed in the RP with a summary of today’s trends in health care design. There are comments about financial implications that could affect how a project is designed and how goals are prioritized, as well as many regional differences that might affect how a health care facility is planned — such as the culture and demographics of the served population.

Within the reference section, there is a list of professional organizations and glossaries of both lighting and health care terms. There is an explanation of the illuminance system used by the IES, including a table of common applications that are not unique to health care spaces — such as for accent lighting, conference rooms, and food service. Finally, there is a list of articles and references that was cited throughout the document so those who are interested in learning more, particularly related to the link between light and health, have resources to dive deeper.

Another change in this version is the use of sidebars. Through the revision process, there were several topics that were noteworthy, yet not necessarily issues about which recommendations should be made. Descriptive verbiage was provided in insets for educational purposes and to inspire design innovation; these are noted in blue-shaded boxes throughout the document. Some sidebars relate to the health care environment — such as the use of green light in operating rooms, or positive distraction. Some sidebars discuss features of lighting equipment — like surgical and exam lighting, or dynamic lighting. Other sidebars relate to emerging lighting research — like the impact of light on the circadian cycle or new color rendition metrics.

Part 1 of RP-29 describes design considerations that relate directly to health care facilities. Concepts discussed are applicable to health care projects in general, and are not specific to a particular room type. Part 1 is organized by sections devoted to comfort, function, safety, health and wellness, and sustainability. Illumination needs of staff and patients often differ. Lighting designers must understand design considerations and facility priorities to address conflicting needs and develop innovative solutions. Part 1 is intended to inform the design community about common concerns so that designers are better prepared to interact with project team members when developing project goals and creative design solutions.

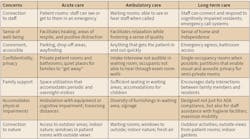

The comfort section discusses areas of respite, glare mitigation, visual interest, and demographics. It also provides a table to illustrate how health care facility can impact design focus (see Table). Designers should be mindful of occupant needs, which vary by the type of health care facility.

The function section reviews the importance of contrast, uniformity, task geometry, and color, and reinforces that age is of particular concern in most health care facilities. Task illumination needs for patients and visitors should generally be met using the “>65” column, using illumination tables that follow the same format used in The Lighting Handbook, 10th ed, published by the IES. The table uses the right-hand, color-coded column to indicate if the illuminance value relates to a task within a room (green) or relates to the room as a whole (yellow). Tightened energy codes necessitate the need for task-ambient designs. The illumination table was updated based on consensus from the careful, room-by-room review used to develop Part 2 of RP-29-16. Unfortunately, some of those changes were mistakenly left out of the original printing of this document. The IES has since issued an errata updating the illumination tables. The errata can be found on the IES website. New orders will include the errata. New room types such as Emergency Department Waiting, Emergency Department Trauma Rooms, Staff Sleeping Rooms, Critical Care Patient Rooms, LDR/LDRP Patient Rooms, Neonatal Intensive Care, Medication Dispensing, Nourishment Areas, Hyperbaric Therapy, Seclusion, Group Therapy, and Telemedical Diagnostics have been added to the document.

The function section also discusses the importance of lighting controls and reminds readers that automated controls should never be used where lights could turn off automatically in the middle of a procedure. The importance of flexibility and way-finding are emphasized, as are needs of special populations such as the aged, pediatric, autistic, and behavioral health. The Health Care Committee has recognized the growing need for behavioral health guidance, and is focusing current efforts to improve and expand upon the work that was started.

The safety section contains principal concerns for health care administrators, identifying how lighting should support medication accuracy, fall prevention, infection control, medical equipment interference mitigation, medical task lighting, security, and photobiological safety. Also in this section, the difference between emergency life safety and critical circuits is identified, and concerns regarding redundancy and single points of failure are discussed.

The health and wellness section explores emerging research that correlates emotional health and comfort with patient outcomes. It also emphasizes the link between circadian systems and physiological health. It is critical for designers to keep abreast of emerging light and human health research, as it is estimated that more than half of all drug-response pathways are circadian clock-controlled.

Part 1 concludes with a discussion on sustainability. Energy efficiency, daylighting, material life, serviceability, minimizing hazardous waste, recycling, and preventing light trespass into patient rooms are all examined.

Part 2 is the room types section, which has been updated to expand the breadth of spaces covered and align terminology and organization with the FGI Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospitals and Outpatient Facilities, 2014 edition. There are four main headings under the Room Types section: General Areas, Nursing Units & Patient Care Areas, Diagnostic & Treatment Areas, and Patient Support Facilities. An overall framework addressing design criteria and strategies was used in developing the illumination recommendations for each area. An overarching outline was developed for each room type that considered each of the following topics:

• Appearance

• Color

• Illuminance

— Uniformit

— Contrast ratio

• Light distribution

• Veiling reflections

• Visual task

• Glare

• Daylighting

• Infection control

• Health and wellness

• Safety

• Controls

• Maintenance

• Nighttime environment

• Systems integration

Key concepts that are new to the update include the importance of healing gardens and the connection to nature, and how light augments these connections in evening and early morning hours (influenced by site section). In the general areas section, the impact of lighting on way-finding and capturing the opportunities for daylight and views are stressed as important aspects of patient and family satisfaction and comfort in health care facilities, and greatly enhance the healing environment.

Nursing units and patient care areas is one of the most significant sections in the updated RP, with great care, research and collaboration put into the breadth of information in this section, including the complexity and challenges of lighting a patient room. Specialty patient rooms with varying needs are described, including critical care, obstetrical, NICU, pediatric (Photo 1), geriatric, and psychiatric. Included in Part 2 are areas within a nursing unit, stressing important issues such as reducing medical errors in medication rooms with quality lighting, and improving infection control through creative lighting control techniques at handwashing stations.

The diagnostic and treatment areas section had a major face-lift in this update, with abundant photography to help designers visualize medical equipment and calming light strategies often used in imaging suites (Photo 2). Part 2 wraps up with patient support facilities, including clinical laboratories and pharmacy services.

Editor’s Note: The IES RP-29 Recommended Practice for Health Care Design is available for purchase from the online IES bookstore. If you have already purchased a copy, please be sure to go online and download the illumination table errata, which corrects several errors in the illumination tables in the printed copy. A recorded webinar on the ANSI/IES RP-29-16 rollout, recorded Sept.17, 2017, is available at www.ies.org/education/electronic-resources/webinars.

Alcaraz, P.E., LC, LEED BD+C is a senior project manager at The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. Murphy, LC, LEED AP, is a senior professional associate and principal lighting designer with HDR in Princeton, N.J.; and Lee, LC, LEED AP, is an industry veteran with extensive expertise in lighting applications and segment marketing. All three authors were instrumental contributing members of the IES Health Care Committee, which authored this new publication. They can be reached at [email protected], [email protected], and [email protected].