The State of Battery-Powered Electric School Buses

Just as more zero-emission package delivery vehicles are showing up on the road, so too are another type of human delivery vehicle: school buses. The number of battery-powered electric school buses (ESBs) in operation continues to surge, and California’s recent affirmation that no new diesel-powered buses will be allowed after 2035 marks another milestone on the path to wider adoption.

The governor’s mid-October signing of the bill mandating the shift solidifies the state as a leader in the transition. Its action makes it the fifth state — maybe the most consequential — to set a date-certain transition; New York, Connecticut, Maryland and Maine had earlier announced definitive phase-outs, but they greatly lag California in deployments.

California had 2,078 ESBs committed — in operation, delivered, ordered or awarded — as of June 2023, according to World Resources Institute (WRI), by far the biggest number of any state. Maryland was a distant second with 391, and New York, Florida, and Virginia rounded out the top five. California has aggressively turned up the dial on ESBs. Two years ago, only 526 were committed.

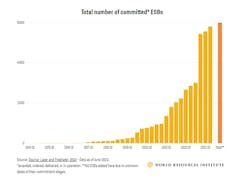

Deployments are accelerating thanks in part to federal and state funding programs that are growing in number and size. WRI put the number of ESBs operating, delivered or on order nationwide at 2,277 as of June 2023. Another 3,700 are awarded and in the pipeline, for a total just shy of 6,000 (see Figure). WRI says The Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean School Bus Rebate Program is the leading source of ESB funding, responsible for more than 2,300 units committed. The California Air Resources Board’s Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program (HVIP) is second, funding more than 1,000. Many of the other top programs are California-based, too.

Electric school bus deployments have been steadily rising, accelerating in 2023.

The buses themselves might be the easiest part of the plans to roll out more ESBs. Well-established and rapidly advancing vehicle battery technologies are making it possible for more existing and conceivably start-up bus manufacturers to build the vehicles, though at a higher initial cost than traditional buses. The bigger challenge may lie in building out the charging infrastructure.

Though many of the top ESB funding sources allocate monies for that infrastructure, the task of planning, designing, and implementing a comprehensive and reliable electric vehicle supply equipment (EVSE) plan for bus operators can be complex.

Surveying the ESB market it is helping to grow from its perch as a facilitator of clean, efficient transportation solutions, CALSTART notes in “Zeroing in on Electric School Buses: 2023” that “for new school districts adopting ESBs, technical support and fleet electrification planning continue to be significant obstacles.” One element of thee Pasadena, Calif.-based group’s “Bus Initiative” is “securing funding for and assisting with infrastructure planning and installation for the largest electric bus deployments in the nation.”

Part of the unique infrastructure challenge lies in the extent of ground-up development needed on many school district properties not originally laid out for delivering the power needed for charging. Utilities, therefore, play an important role in assisting operators in the design and construction of a charging hub subsidized through development assistance programs, according to Rachel Chard, CALSTART’s national program manager, electric school buses.

“Many incentive programs, including the EPA’s Clean School Bus Program and California’s HVIP program, are pairing charging infrastructure funding with bus funding and encouraging school bus fleet operator to connect with their utilities early to help plan for necessary infrastructure improvements,” she says. “Utilities are adjusting by solidifying their connection and upgrade processes and engaging with fleets earlier.”

EVSE design considerations for ESB operations must reflect numerous priorities, notably rigid scheduling, safety, specific vehicle compatibility, maintenance demands, grid capacity, power sufficiency, and reliability.

“The design of the system will focus more on safety and efficiency,” Chard says, meaning that fleet operators will be concerned with operational factors like power location, parking lot layout, bus charging port location, and cord management.

Another layer of complexity that could come into play for ESB charging infrastructure is bidirectional charging capability. Equipped with large batteries and frequently in operation in limited time windows, ESBs and the charging infrastructure can be configured to allow connection to the utility electrical grid, becoming a source of stored power at opportune times. Such vehicle-to-grid (V2G) applications could emerge as a source of charging infrastructure funding, furthering the case for ESBs as a superior alternative to traditional school buses.