What started out as a beautiful day at the lake quickly turned to tragedy for a grandfather and his grandson. The pair headed out to enjoy the warm waters of Lake Waccamaw, N.C., with the intention of playing under the dock in 3 ft of water. However, by raising the boat lift to allow more room, the grandfather inadvertently exposed a live 120V line to the hands of a child.

The scene

Lake Waccamaw is a beautiful lake with depths that average 6 ft to 10 ft in most places and 2 ft to 3 ft along the shoreline. Many lakefront owners have a long walkway leading out to a wooden dock. This particular covered dock, located about 200 ft out on the lake, contained a picnic table, barbecue grill, motorized boat lift, ceiling fans, and two staircases that descended down to the water's edge — overall, a very nice place to swim and enjoy the lake (Photo 1).

On this day, the grandfather/grandson duo decided to go swimming in the open area where a boat would have been located. Because he did not own a boat, the grandfather lifted the metal rails of the boat lift about 2 ft out of the water, operating a 1-hp motor connected to a pulley system with metal cables. Normally, the grandfather let the rails sit in the water.

The accident

As they were enjoying themselves in the water, several neighbor children (ranging in age from eight to 13) decided to join them. Everyone gathered under the shade of the covered dock, in and around the raised metal boat lift and 3 ft of water (Photo 2).

Out of the corner of his eye, the grandfather noticed a child hanging and swinging from the metal rails. He immediately told the child to get off, which he did. A short time later, another child said he felt a tingle on his legs. Immediately dismissing this claim, the grandfather maintained this was not possible. The child, standing in the water and not touching anything, continued to insist he had felt a tingle. Perplexed, the grandfather cautiously walked up to the metal rails and touched them. Feeling an electrical shock go up his arm, he advised the children to “Get out of the water, now!”

Everyone scrambled out of the water, climbing the nearest stairs onto the wooden deck surface. As the grandfather assessed the situation, standing near the lift controls, he looked down into the water and saw a child floating face down in the water. He called out to him, but did not get a response. Not knowing who the child was, he asked another child if he was playing a game. That child jumped into the water, raised the boy's head, and found him to be unconscious. The grandfather immediately brought the child to the deck's surface and administered CPR, while his wife dialed 911. When the emergency medical staff arrived, they couldn't revive the child, pronouncing him dead at the scene (cause of death was electrocution).

The investigation

After the tragic accident, the family of the deceased boy, as well as the grandfather (homeowner), wanted answers. How did this happen? Where did the voltage come from? How long had this situation existed? These and other questions were going through everyone's minds when my firm was called in to investigate this accident on behalf of the grandfather, who was being sued by the victim's family (who also sued the electrician).

Once at the scene, I started my investigation, logging data and interviewing the grandfather and grandmother. Based on this initial visit, I was able to ascertain several clues.

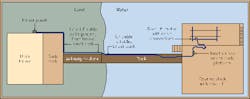

The dock was fed by a UF (underground feeder cable) 12-2 rated cable with ground, which was routed from a junction box located in the house's crawl space (see Fig. 1 and Fig. 2).

A UF cable is suitable for direct burial in the earth. A portion of the UF cable ran along the edge of a deck, exposed to the environment and foot traffic. Fed from a 20A circuit breaker at the main panel, a bare ground wire in the junction box appeared awkwardly twisted onto a shorter ground wire. I later learned from the town's electrical inspector that he had found this wire hanging out of the junction box, and it was severed at that point (Photo 3). Upon seeing this, he had reconnected it, to prevent any other ground issues.

The inspector stated that the dock was originally built without electricity, and whoever did the wiring never obtained an electrical permit. The grandfather recalled that a local contractor had completed the work, and did not recall if he had seen the permit (the dock had a certificate of occupancy but without electricity). I surmised there was no telling how long that ground wire had been severed.

The electrical inspector also informed me that he had located and opened a sealed standard plastic junction box under the wood dock and above the water line. He identified that the internal wires served the boat lift motor and were spliced to the house wires with twist-on connectors. When he removed the cover screws, water poured out of the box. He identified that the ground (green) wire and the phase (black) wire of the 120V UF cable were on the bottom of the box. I noticed a line on the inside of the junction box, suspecting that this was identifying the water level inside the box, with the two wires clearly being below the line (Photo 4).

The house panel's circuit breaker for this circuit did not have a ground fault circuit interrupter (GFCI) as per the 1995-1998 NEC, Art. 555, Marina and Boatyards. I noted that the boat lift motor had two GFCI devices connected in series, in between the boat lift and the plastic junction box, located near the boat lift motor switch.

This made me ask myself: If there were two GFCI devices in series, how did the electricity get from the black (hot) wire to the metal rails of the boat lift? The motor casing was metal, and was directly attached to a metal plate, which was attached to metal cables supporting the metal rails. Therefore, an internal short in the motor's casing would energize everything back to the metal railings. Or maybe the two wires in the junction box below the water line were the source of the short. Either way, the severed ground wire under the house would not have allowed anything to flow back to the panel's ground bus.

A ground wire provides a safe return path to ground for any leakage or fault voltages. An internal motor short would result in tripping the circuit breaker, or leakage imbalance would trip the GFCI circuit. However, with the ground wire severed at the house, electricity could not flow on this wire. Therefore, there would not be a GFCI sensed voltage imbalance at the lift motor to trip the unit. Both GFCI circuits were on the up side of where the short to ground was located. Effectively, this said the GFCI became unusable as soon as the ground wire became severed.

If the GFCI circuitry was unusable, then the house circuit breaker was the only way for the electrical power to the motor to be interrupted from an overcurrent condition. But while not operating, there would be no current flowing for the house circuit breaker to trip.

Something else the grandfather said proved to be a useful clue in the case. Occasionally having a problem activating the boat lift, the grandfather said it had appeared sluggish to start and made buzzing noises in the past. This made me think that at these moments, the motor might not have been receiving sufficient voltage due to leakage into the lake; therefore, it could not turn the motor shaft to drive the boat lift.

I had to prove that the motor had an internal short to its casing, which would place 120V on the metal cabling and metal boat rails, or that the plastic junction box was filled with enough water to allow a conductive path between the black (hot) wire and the “floating” green (ground) wire. But how was I supposed to do this? The motor was hanging 15 ft to 20 ft over the water, with no means to place a ladder up to it and no way to prove that the water-filled plastic junction box was the conducive path (Photo 5).

The findings

I made a second trip back to the house and took along my digital meter and some hand tools. I decided that if I could prove or disprove one of the two possible causes, the answer would fall out. In order to examine the motor for an internal short, I disconnected the ground wire going from the house to the motor and then energized the motor via the power switch. I made a voltage measurement between the motor's ground wire and the ground wire going back to the house. I measured 0V, which told me that there was no voltage on the motor's casing. Therefore, the only other path would have to be through the water-filled plastic junction box, back to the motor's ground casing, and down the metal rails. No ground connection back at the house meant the metal rails remained energized until a grounding connection could be made somewhere.

Because the boat dock is made of wood, anyone standing on it would be isolated and would not receive a shock by touching the metal cables during normal boat lifting operation. This also was true if you were to stand inside a boat supported by the rails — a person would have to make direct contact between any metal and the water.

When the grandfather lifted the rails out of the water, he disconnected the leakage path, allowing the electricity to remain on the rails. Unfortunately, when the boy hung from the rails with his feet in the water, he provided a direct path for current to flow.

However, how the water got into the gasketed, sealed, junction box remained somewhat of a mystery. The wiring feeding the junction box was encased in two plastic conduits, but they were not sealed from the outside humid environment, possibly accumulating condensation over time. The section routed toward the house stopped about halfway along its length. The other section was routed vertically partially up to the GFCI connector. Therefore, both ends were open to the elements.

I also noticed that the plastic junction box was located directly under a seam in the deck boards. If the cover was not sealed completely, its location would be ideal for water to drip into the box. Either way, it was likely that the internal water buildup took a long time, possibly starting from the first day that the uninspected wiring was installed.

The verdict

The final outcome of this case against the grandfather (my client) was settled out of court for an undisclosed amount. The outcome of litigation between the boy's father and the electrician is unknown.

The recommendations

First of all, an electrical permit should have been obtained by the electrician. The inspection would have uncovered the missing GFCI at the house, and the connection under the house would have been installed to NEC regulations, preventing the severed wire. Eventually, water buildup in the plastic junction box would have tripped the GFCI. Then, the subsequent troubleshooting would have uncovered the problem and led to the fix, which sealed the conduits and the plastic junction box.

The quirky piece of this puzzle is that individually the severed ground wire and the water buildup would not have caused this fatality. But together, a dangerous electrical condition was lurking under the surface, waiting for someone to provide the grounding connection.

Lessons learned

Don't assume that because you see a GFCI circuit interrupter in-circuit that you are protected from a ground fault. Always insist that anyone doing electrical work for you gets an electrical permit. Although this does cost money, in the end, the customer can rest assured knowing that a qualified electrical inspector will make sure the electrical installation is completed within the confines of the NEC.

Cavallaro, P.E., CFEI, is a forensic electrical engineer and certified fire investigator with Forensic Engineering, Inc., Raleigh, N.C. He can be reached at [email protected].