Streamlining the Energized Work Permit Process

Filling out paperwork for electrical permits and inspections and submitting a drawing to the local building department for plan review is already time consuming. Now, in order to be compliant with NFPA 70E, more in-house paperwork is required each time a worker reaches into energized equipment.

Changing breakers and pulling/terminating wire into panels are tasks performed frequently by electricians. Who can possibly follow through with this requirement? By reading between the lines of 70E and creating two types of energized permits, contractors can eliminate large amounts of paperwork. Better yet, they will soon find that the “energized work permit” is the best place to start for both worker and company safety.

Permit requirements. Section 130.1(A) of 70E was added in the 2004 edition, requiring a permit for any “hot” work. A sample of this permit can be found in the 70E annex. While it was not the intent of 70E to provide a specific permit form, some key elements that need to be included are as follows:

-

Description of the work to be performed.

-

Justification for the work.

-

Proper personal protective clothing (PPE) to be worn.

-

Results of shock and flash hazard analysis.

-

Signature of approval by management.

-

Evidence of completion of job briefing.

Adding permits to the 70E standard was done for several reasons — one of which was to actually discourage or eliminate energized work. Obtaining management's approval and signature to send someone into an energized panel was considered less than likely. For those projects where a signature was obtained, filling out a permit was considered a reminder for qualified electricians to think safety prior to the actual start of work.

Just as with other permits, however, some companies may avoid energized work permits. Why? There are several reasons. For starters, to make sure work is not delayed and profits are not decreased. Many companies and their workers may also feel that purchasing gloves, protective clothing, and insulated tools will reduce their exposure. Although many times it will, this is not always the case. An energized permit takes time, and is widely considered as a bureaucratic step that's not necessarily important. Even though skipping the permit process may create problems with OSHA down the road, the immediate benefit is not quickly perceived. Oftentimes, this mindset stems from lack of information.

Understanding the benefits. To get companies to start an energized permit program, they must see the permit as both simple and beneficial. Using in-house permits will reduce a firm's exposure to workplace injuries and at the same time provide specific documentation of who is capable of working on energized equipment — and who is not.

This documentation is extremely important in case of an accident, when OSHA comes knocking on your door. As companies grow, trying to keep track of electricians can be quite difficult. Think monitoring 10 employees can be tough? Try 50! Add to the mix the chore of figuring out who in that group is qualified, who can work on what system, and who is wearing the proper PPE, and you need a full-time safety director. Furthermore, various pieces of equipment — from load centers and panelboards to motor control centers and service entrance switchgear — can require a whole different level of expertise.

Shortages of electricians can also create problems. As the workload increases, it may be weeks before additional electricians are hired. Non-qualified workers inevitably end up on jobsites by themselves and are unfortunately asked to perform work that is above their pay grade or skill level.

New apprentices are quickly hired and placed in the field with shiny uninsulated screwdrivers and tools that are not voltage rated. New hires are given company-issued safety glasses and hard hats with little or no direction. These same workers can end up in buildings within large downtown electrical grids with high fault current levels at each panel. Do they know the energy levels behind these covers? Are new hires told not to work on energized circuits? Do they know what “qualified” means? Does management know which workers are reaching into energized equipment?

An energized work permit program can answer all of these questions and more. Determining who is qualified should take place prior to handing out PPE and voltage rated tools.

Routine and non-routine energized work permits. After reading 70E for the first time, you may get the impression that energized permits are required for each and every task. However, this is not the case.

According to the commentary in the 70E handbook, routine energized tasks can be grouped under one permit for a longer period of time. To handle these longer timeframes, a variation of the basic permit should be created. For instance, you might want to draft one to cover a one-year period. Companies can alter this timeframe to meet their needs. After one year has passed, management should review worker qualifications to make sure nothing has changed. This review can coincide with a worker's annual performance review, at which time new updated permits can be issued. Specific tasks should be written on the routine permit form so both electrical field workers and management clearly understand what “hot” work is permitted on a daily basis without further scrutiny.

What is considered routine may vary from company to company. One approach can be to consider routine work on panels 400A or less. Work below this threshold typically involves small 15A or 20A breakers of the plug-in type. Panels greater than 400A usually involve larger and more awkward breakers and higher incident energy levels where greater caution should be taken. In either case, a company should determine what it considers “routine.”

For all other energized work, a base permit (non-routine) should be used. This permit will cover non-routine electrical tasks and would be only good for as long as it takes to perform that task. Adding feeders into a large piece of gear, replacing 2000A fuses, and adding a bucket into a motor control center are examples of tasks that are not performed daily. A non-routine permit will need to be filled out each time such tasks are performed. This permit must also be signed and filled out by both management and electricians prior starting work.

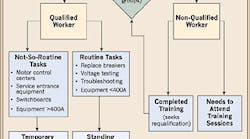

Implementation of permit program. Once two permit forms have been created, some additional legwork is needed. Management should split electricians or company maintenance personnel into two separate groups: qualified and non-qualified.

There are certain employees in your company who make difficult jobs look easy, always making sound decisions in a clutch. You know, the ones you can leave alone to do almost anything. These are the well-qualified workers. There's another category for non-qualified personnel — the ones who have not quite finished the apprenticeship program or those that do not have the confidence from management in successfully completing “hot” work.

Every company has employees that fit into one of these two categories (see Flow Chart above). After employees are categorized in one of the two categories, employees should be informed of where they fit, allowing them to better understand their roles and capabilities. In addition, supervisors should explain to electricians the necessary steps required for someone to move from the non-qualified to qualified side of the house.

Once your field personnel have been divided into groups, a company meeting should be held to communicate your new approach. Workers should be educated on the difference between routine and non-routine type permits. Electricians should be instructed that “hot” work will only take place with written authorization. A company may have 50 journeyman and apprentice electricians but only 20 of them may be considered qualified. Typing up 20 annual energized permits and keeping them on file will provide documentation that the remaining 30 field workers are not allowed to work on equipment “hot.” The company handbook should be updated to reflect this new way of thinking.

One bad electrical incident on one job can take a company down. Understanding this reality reiterates the importance for companies to create documents to keep employees from working in areas they are not trained to be in. While arc flash and incident energies are the buzzwords of today, worker safety starts with training and keeping non-qualified personnel out of harm's way. Labeling qualified workers, creating energized permits, and updating the companies handbook will go a long way to reaching that goal.

Ayer is vice president of Biz Com Electric, Inc., in Cincinnati and is a member of the NFPA 70E Committee.