Do you ever feel like a doctor calling for a scalpel in the critical moment of surgery — but without a nurse or scalpel to be found? Or like the racecar driver who shows up to a pit stop with only three tires available for change-out? Every minute on every job is spoken for, and the fewer minutes your electricians spend worrying about the material, the more minutes can go to planning, prefabrication, and installation. Assuming the material is locally available, this article will give some simple tips on how to order it to assure you (and your electricians) aren’t left stranded and unproductive.

Our last EC&M job-site intelligence article, “Who Is Calling the (Material) Shots?,” shared MCA’s recent research on job-site decision-making, highlighting how the material-related decisions are (most of the time) left to be managed by field personnel and offering considerations that you can put in place internally in the company or project to improve productivity.

In this article, we continue the discussion around material handling, but rather than looking internally at the decision-making, we will focus on the vendor-related factors that influence material handling on the job and strategies to work externally with a vendor so you can get the material you need to the job when you want it, where you want it, and how you want it. Vendor sales reps or inside sales/order writers cannot read your mind (although some do a good job trying!), and their main interest is selling you the material they can look up in their ERP system and getting it to you ASAP. However, this does not guarantee you will have the best experience in the delivery and receipt of such material. Your electricians need to supply the information that isn’t always asked for, such as:

- What you want

- When you want it

- How you want it

- Where you want it

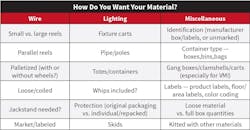

The difference between a next-day delivery and a two-day lead time is a 30% or better chance that you’ll get what you need, according to Agile Distribution: Application of Lean Principals, by Dr. Perry Daneshgari, president and CEO of MCA, Inc. However, getting to the ideal state is not as easy as it should be until Agile Distribution® becomes the norm where the distributor’s role shifts from parts suppliers to Integrated Material Logistics Solutions (IMLS®) providers. In the current state of the industry, your electricians, project managers, purchasing department, and dispatchers need to give the right and full information to their inside salesperson at the supplier to get the right outcomes shown in Table 1.

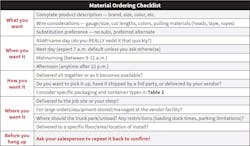

When ordering material for your job, consider what you want, when you want it, how you want it, and where you want it to make sure you get the materials you need in the most efficient way for installation.

What you want

As shown in Table 1, making sure you are specific when providing complete product information can help reduce potential errors later. This means being specific about the product name, manufacturer (if there is a requirement/preference), and quantity needed. For wire, this can be especially important to make sure you have the correct type of wire at the correct length.

When you want it

Being specific about when you want your material delivered can help make sure the product doesn’t arrive sooner than necessary. If not specified, you will likely get the product at the earliest available day and at the earliest available time, which may or may not work with your schedule. A few options for this, as shown in Table 1, include:

- As soon as possible/same day (do you REALLY need it that quickly?)

- Next day (expect 7 a.m. default unless you ask otherwise)

- Mid-morning (Between 9 a.m. and 11 a.m.)

- Afternoon (anytime after noon)

When deciding which time of day works best for the crew on site, consider other trades' delivery schedules, what your crew is working on, and if they need the material tomorrow or the next day. Following the Short Interval Scheduling (SIS®) approach, discussed in our previous EC&M article, can help ensure you are looking ahead to get what you need on time and track vendor-related delays that may impact installation.

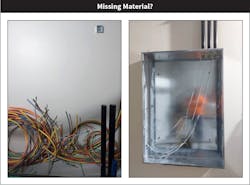

Planning for when you want it can help make sure you don’t run into the situation shown in Fig. 1, where a foreman wasn’t able to complete piping for a UPS and found themselves with both a wiring/no panel and panel/no wiring combo, shown in Fig. 1.

How you want it

Thinking about how you want the material to arrive is often overlooked. But it's incredibly important to make sure the person on-site receiving and handling the material can identify the product correctly and avoid unnecessary time spent searching for the product or unpacking it.

For the order overall, clarify if you want the products to all come at the same time or as they become available. If they can be shipped all at the same time, this can help avoid daily deliveries and time spent making the trip to the loading dock/drop-off location each day — but it may not always be possible depending on timing needs.

If you don’t specify, you may get four deliveries during the week with one item delivered at a time, creating more work for your crew to move material to the site drop-off location.

Depending on the type of product (lighting, miscellaneous, wire, etc.), check with your vendor on the options in Table 2 for how the product arrives at the job site.

Where you want it

Last, but not least, it is important to plan where you want your material delivered. Do you want it delivered directly to the job site or the shop? Where do you want it on the job site? If you find yourself in a situation like the one shown in Fig. 2 — and the loading dock is backed up with other trades’ materials — you may want to ask your vendor about temporary storage at their facility so that when it is delivered, there is space available for it.

Additionally, you may be able to plan with your vendor to specify the on-site location you would like your material delivered to, which can save your crew time moving your material to the point of installation.

In conclusion, dealing with material issues can be time-intensive and a major source of waste on the job site. By looking at ways you can communicate externally with your vendor when placing your orders for material, you can save you and your crew time looking for and carting material around.