You have many jobs of varying sizes. If we ventured a guess, we’d say that rarely do these jobs deliver the profit that was identified in the estimate. And if they do, the portion of the job where you made the profit was likely not where you expected to get it. How do we know this? Based on 30 years of studying the construction industry and data on millions of hours of construction projects, almost no projects turn out how they were bid. The root cause is a lack of visibility to the realities on the job site.

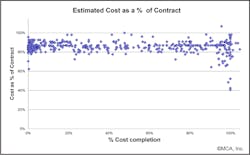

Take a look at Fig. 1. MCA, Inc.’s data shows that while the estimates planned for a profit range of 12% to 24%, at the end of the job, the range was actually -12% to 42%. It’s difficult to comprehend this because the team believes and intends to be observing, discussing, and attempting to monitor the job throughout its lifecycle. But the numbers don’t lie.

Ask yourself these questions:

- How often have you and your team watched the accounting job cost report and watched the burn rate on the job?

- How often do you see job profit projections “holding steady” month after month?

- How much attention do you put into your schedule of values to ensure you’re working to avoid financing the job?

- How often do you review under and overbilling?

- How often do you have work in progress meetings to discuss the status of the job?

You spend all this time with your team, reviewing the numbers, but you still end up with an outcome you don’t expect. So what are you missing?

Identifying the variation

Companies have various methods of tracking costs and profits. There are signs that things aren’t as stable as you’d like. You meet weekly, reviewing the status of the job by looking at the costs and the billings. It all looks under control, but then something changes at the end. The discussions throughout the job could include some of the following items:

- Depending on your method of tracking, you may hear that the percent complete of the job matches the percent labor spend through most of the job — until the end.

- If the labor is over budget, you may hear that “we’re waiting on approved change orders.”

- When you’re close to substantial completion, you’ll hear that “we’re almost done,” but then that last 5% takes a LONG time to get to 100%.

- You’re in the project management/work in progress meetings, asking or answering questions about projected profitability on the job and you hear, “We’re on track. There are no changes to report. Everything is going fine.”

MCA’s data in Fig. 2 shows that the real costs on the project – if labor and job productivity are not tracked – will likely show up when the job is close to 95% complete. And then what?! You have that last (long) 5% to finish and there aren’t a lot of knobs to turn to recover if you’re behind, or even explain why you’re ahead.

How can you help the situation?

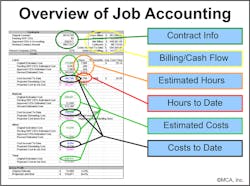

The old saying is as true today as when it was first said: “What gets measured gets done.” It is also true that only what is visible gets measured. This takes a reference point/yardstick to measure performance against. This takes real-time data between estimating, the field, and accounting to triangulate to ensure that the answers you’re getting in those meetings are grounded in data. Figure 3 is an example of a report that links money, manpower, and material from the field, accounting, and estimating. The best way to predict profitability is to control the job during the job. The key to this is to measure productivity instead of production. Refer to ASTM E2691-20, Standard Practice for Job Productivity Measurement, which was originally published in 2008 and republished in 2012. The questions you should ask are:

- Do the hours/labor/cost codes planned for the job match how the field sees/will build the job?

- Are the cost codes being managed weekly to check for under/overruns (versus one large bucket of labor)?

- How much work was planned for today versus how much was completed? If the completion didn’t meet the plan, why not, and what are you doing to help that?

- What got in the team’s way of completing their work?

Putting it all together

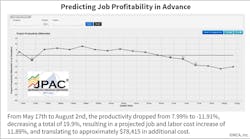

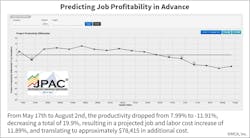

Figure 4 shows a real-life example of a team using all of the points listed above (accounting cost reviews and project management percent complete projections) and following the recommendations in the ASTM E2691-20 Standard. Using the standard and labor productivity (versus production), the signals that the labor was not productive and the profitability of this job was at risk were present as early as March 2019 (when the job started up and the estimate/planned work had a difference). Then in May, the tool showed downward productivity. Since this was a five-month job, this early notification was quite significant — and likely could’ve helped job profitability if acted upon. The ending accounting/company reports confirmed what the tool using ASTM Standard E2691-20 had been displaying.

So, let’s focus on how you can use this process. First, create your reference points:

- Track costs in your accounting/project management/work-in-progress meetings, but recognize you need a link to an independent reference point related to the completion of work.

- Don’t go by gut feel for percent complete on the job. Watch this plan frequently. Take job walks, review with your team what they see in the field, and help them see things they may be missing.

- Get the field workers to document the work they see on the job. Write it down with a daily plan. Don’t focus on what was completed by the end of the day, but on what you scheduled. Then note what got in your way, according to the article “The Secret to Short-Interval Scheduling.”

- If they’re spending time mobilizing/demobilizing for other trades or general contractor requests, document it and the time you’re losing.

- If they’re spending time moving material, consider breaking down the work to tasks you can have different people (or vendors) help with to keep your most valuable and skilled labor doing what they do best – installing. For more information on this concept, read the article “Real Ways to Reduce Material Handling Costs.”

- Figure out anything that can be taken off the job site and completed in a pre-fab shop to help with safety and speed of installation, according to the article “Putting Prefab into Perspective.”

If you focus on data and linking estimating, accounting, and field information through an application applying ASTM E2691-20’s Standard Practice for Job Productivity Measurement, you will not be surprised in the last 95% of the job. You’ll be able to effectively predict your profits to accurately plan for the future.

Dr. Heather Moore is the Co-Chair of ASTM Building Economics Subcommittee E06-81 and the vice president of operations at MCA, Inc., Grand Blanc, Mich. She can be reached at [email protected]. Jennifer Daneshgari is vice president of financial services and operations at MCA, Inc. She can be reached at [email protected].