Every business starts with people doing things that they know how to do best. And if what they do ends up being what the customer wants — and is willing to pay for — then the business starts to grow.

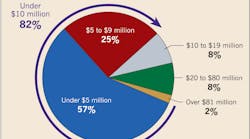

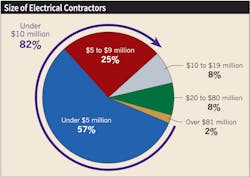

In the electrical market, many contractors are able to do this by simply being good electricians. It is typical for electrical contractors to grow their business and hit $2 million to $5 million in annual revenue in a matter of a few years. As shown in Fig. 1, 82% of electrical contractors fall in the “under $10 million” revenue category.

But when the contractor does a good job or the economy heats up, the company begins to feel the pressure. At this point, the owner or management team begins to seek guidance on how to better manage the business. They might do so through seminars or industry trade shows. They return from these events with a few new forms and processes or new software/tools for their people to use. However, the processes that the forms and software should be supporting are not yet formalized in the contractor’s business, so they don’t end up turning into actual procedures. Worse yet, any investment in IT equipment and/or systems without training in how to use it can create more problems — even going against the existing philosophy of operation.

The reality is that people still do what they know how to do. The guys in the field still order at 3 p.m. and expect the material to be delivered to them the next morning at 7 a.m. If they are sophisticated, they may take a picture of their order, which was written on the back of the lid of the cardboard box and text it to their local supplier. But, in the end, it’s extremely difficult to enact any substantial change in thinking among the staff.

For those electrical contractors that grow their business to $15 to $20 million in annual sales, the national conferences and seminars are no longer sufficient to help them turn processes into procedures. Only 8% of electrical contractors are fortunate enough to achieve this level of sales volume These contractors have a hard time finding others who “get it” or who have been through the painful experience of growing their business this big.

The owners or principals of these larger companies then start joining peer groups. But the focus of many of these peer groups is typically financial and seldom helps the contractor establish the processes and procedures required to run the company. Another mistake these contractors make is to rely on out-of-the-box software to run their business, which very often does not match their specific company needs.

Figure 2 shows the evolution of organizations, which starts and is built on the foundation of its people and philosophy of operation. The business can only grow successfully if that philosophy is transferred into process (how work is done), then procedures (standardized and scalable support for processes), and then IT (automated support to improve efficiency and reduce errors). What is missing in the approach of many peer groups is the supporting infrastructure and processes to sustain the procedures and IT solutions. Focusing purely on the financial output, even though necessary, is like driving on the highway by only looking in the rear view mirror. It is an after-the-fact measure and a lag indicator.

There are other types of peer groups or peer group facilitations that focus on “strategic planning,” but these are top-line driven only. Once the contractors reach the $20 million or larger level, it is essential that they continue to cover their overhead to sustain and grow their business. But this growth is not sustainable in the long run without focus and feedback from the source of work. For the peer group to work, the participating companies have to start from the back end, which is the way the jobs are run, and assure the leading indicator measurement can give the growing company course correction from jobs upward toward the final financial outcome.

The methodology used in most industries to support growth and assure correct process design for the contractor’s needs is business process improvement. Strategic breakthrough process improvement was developed on successful application of the scientific method in service industries.

Figure 3 shows an overview of the four phases and eight steps of this process. The rigor of this approach ensures that the philosophy of operations translates into process and procedure with top to bottom input from the company using a design team infrastructure. Contrary to “best practices” that peer groups often introduce, where the peer group members try to copy models from their peers, the strategic breakthrough process approach focuses on creating models based on guiding principles of system design. If a similar approach was used by the peer groups, the learning between member companies would be at the process and procedure level, but beyond just “copying and pasting” a form or a tool.

For example, the peer group members can learn from each other how the process of requesting prefab material from vendors or a prefab shop is designed, and tailor it to their specific business applications. Figure 4 shows a sample of a process flow for the prefab operation of one company.

So, to answer the question of “do peer groups work?” we first have to understand what the group’s objective really is. If it helps in the transformation from an unstructured to structured environment with supporting processes and validation via the group, then it is a good thing. If it is just a financial group comparison and review, then it most likely will not help a contractor grow.

If you’re company is part of a peer group, do you know how to evaluate its effectiveness? The following questions should help you determine its value.

• Has your business’ profitability improved?

• Have you been able to leverage relationships you’ve built in this group to improve system productivity?

• Has your middle management team designed visible processes as a result of learning from your peers?

• Have you worked with your peers on more than just financial comparisons?

• What would you miss most if you stopped participating in this peer group?

Daneshgari is the president/CEO of MCA, Inc. He can be reached at [email protected]. Moore is vice president of operations for MCA, Inc. She can be reached at [email protected].