If you have ever solved a Rubik’s Cube, you know the look of awe on faces of those who have not. The ability to go from an orderly, same-colored set of six sides to chaos of unmatching colors and then back to complete order seems to require some fancy wizardry. There are many approaches to unscrambling including:

- Dedicating hours of your life to work one cube at a time back in its original place.

- Peeling off and reapplying the stickers so you have a uniform color on each side (however, this leaves some nasty evidence).

- Recognizing the pattern in a solution, and mastering it in a matter of a few moves within minutes or seconds.

The time involved with option No. 1 usually reduces interest in trying (at least a second time). The poor-quality result of option No. 2 also leaves little to be desired. Option No. 3 becomes a solution for those who seek to categorize, codify, and find patterns to make their life easy.

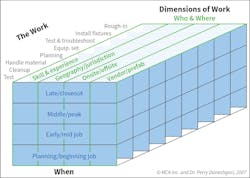

What does this have to do with job-site intelligence? The Rubik’s Cube and the “work cube” (Fig. 1) are the same. There are only so many permutations and combinations of work in electrical construction, so mastery is a matter of pattern recognition, using experience or Agile Intelligence™ with the experience of many. Despite constantly hearing that “every job is unique,” or “we can’t use our normal approach on this job because…,” we will show you that construction jobs have more in common than not.

A project, by definition, is a temporary endeavor to create a unique product, service, or outcome. Construction projects are often characterized as complex, special, or unique — because the deliverable is one of a kind. As new models for construction are introduced that change the way contractors, owners, general contractors (GCs), and architects interact — such as on IPD or GMP projects, this can add another layer of uncertainty.

What makes a project special? A unique project for one contractor or project manager may not be considered unique by another. MCA’s research on the Industrialization of Construction® has shown that there have been minimal changes to the construction process over the last few centuries. Yet, contractors struggle to take advantage of learning across projects, practice consistent project management processes, or even avoid expanding into new markets altogether, citing the reason that the project is “unique.”

While no two projects are the same, ignoring synchronicities and dismissing any means of control because of the project’s uniqueness can be a risky mindset. Vice versa, seeking to standardize every aspect of a project is also not the answer.

Rather, contractors can successfully expand into new markets, environments, and geographies by implementing flexibility in the organization that allows resources, information flow, and risks to be assessed and responded to across the entire operation, while maintaining control of even the one-off types of projects. Project control is essentially getting the project to go the way it is intended to. Control can be achieved through the application of project management processes and the adoption of a resilient operation.

By recognizing the common patterns — and checking for these patterns across your job sites — problems or situations that may seem like discrete events no longer have to be resolved and managed that way.

Job-site patterns

Like a Rubik’s Cube, construction projects can be unscrambled by finding the patterns. MCA, Inc. has been collecting short-interval scheduling and job productivity assurance and control data from thousands of contractors on construction projects totaling over $3 billion since 2003. The methodology and principles published in EC&M’s 2009 article, “The Secret to Short-Interval Scheduling,” allow contractors to categorize impacts to scheduled work.

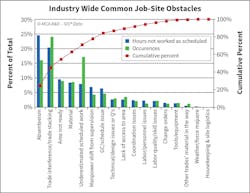

In 2019, MCA conducted a study to review the codification of obstacles across the projects and identified common reasons for impacts on scheduled work. These job-site obstacles were codified and are now referenceable in the ASTM Standard Practice for Job Productivity Measurement, E2691. Findings from the study showed that the following obstacles — independent of the type of work, contract type, and location — were prevalent and accounted for 60% (cumulatively) of obstacles industry-wide (Fig. 2): absenteeism, area not ready, trade interference, and material issues.

While your job’s contract, scope, size, location, or other factors may be unique, our data shows that the obstacles above are not, and they are part of the twists that a work cube can encounter, which need to be mastered for unscrambling and reducing wasted time and effort on any project.

Identifying patterns on your job sites

While every project may have a unique deliverable, the construction process and obstacles encountered along the way are common from job to job. Rather than treating each issue as a discrete event, contractors can start looking for patterns and use tools like short interval scheduling to measure and then design solutions to manage, respond, and resolve these common causes across projects company-wide.

If you aren’t using Short-Interval Scheduling (SIS®) and want to see these patterns with your own eyes, visit a job site. While on site, ask yourself the following questions about each type of common job-site obstacle.

Labor/absenteeism

- Does the labor on site match the planned work and schedule for the day?

- If people are off, what was the reason given?

- Does the labor schedule need to be updated to account for school and training schedules of part-time members of the crew?

- Are prefab or vendor services in use on the job, which can help level the onsite labor requirements? Are there opportunities to put this in place to reduce the impact of absenteeism on site?

Material

- Where is on-site material stored/staged?

- Where are the tools and gang boxes located?

- Is the material organized, labeled, and staged near the installation location?

- How much material is lying around the job site?

- How much movement of material is required?

- Are deliveries managed at a scheduled time?

- How often do you expect deliveries? Can this be reduced to minimize the time spent handling material?

- Are deliveries from the distributor on time?

Area not ready/trade interference

- How many other trades are on site? Where are they working?

- Are the other trades working according to the GCs schedule?

Additionally, ask yourself: How does coordination take place between the trades? Is there a daily huddle? And do you foresee any trade interference or delays in the ability to work in one area due to the schedule being off track?

Labor is often so busy doing the work that they don’t see the obstacles. They only report problems half of the time and encounter them in nearly 90% of their work activities, as outlined in “Exploring Information Generation and Propagation from the Point of Installation on Construction Jobsites: An SNA / ABM Hybrid Approach” by Dr. Heather Moore in her PhD dissertation at Michigan State University. The SIS process solves this, with a proven process for daily scheduling of work and scoring the results. Obstacles reported become visible in real time for managers to monitor and respond to.

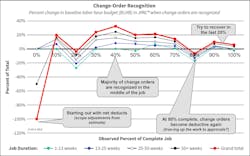

Another pattern across construction job sites is change-order management. With data from several electrical contractors, we have measured that projects “expand” 30% to 40% from changes — some attributable to contract changes (i.e., change orders) and some due to changes in scope and misses in estimating and planning. Managing these changes is challenging, no matter what size, scope, or type of job you’re running. Figure 3 shows how similar the change-order behavior is across 200 projects spanning four years. Notice that change orders are recognized very similarly at each stage of project completion — almost independent of job size.

Solving the cube

While a single project may seem unique, keep in mind that there are limited maneuvers to get a scrambled cube back in order. By studying the patterns across all your job sites with data — and backing them up with your observations on job sites — you can focus on the common pain points and be prepared to take advantage of the solutions on projects of all shapes and sizes.