What keeps electrical professionals up at night? According to a recent survey of EC&M readers conducted in August 2019, things like work-life balance concerns, staffing issues, and the ability to stay on top of emerging standards and technologies are top of mind for many, but overall most respondents are feeling pretty good about their calling.

In a period of historically low unemployment and against a backdrop of slow and steady economic growth, the nation’s workers have been slowly turning the tables on employers in recent years. Paychecks are growing, opportunities for switching jobs are expanding, and overall working conditions may be improving as companies try to stem the flow of discontented and now options-rich workers out the door. Yet, at the same time, many businesses are scrambling to meet demand and seize opportunity in a vibrant economy, balancing the need to be responsive to employee overwork concerns with the need to ramp up output and productivity. Caught between the need to keep workers happy and get more out of them, businesses are searching for the work delivery formula that will keep revenue coming in the door, profits up, and stakeholders of all stripes happy.

The result is a current workplace environment that reflects a pressing need to get the job done right — whatever it takes. Employers are paying for that with higher employee compensation, rewarding presence, performance and longevity, and bowing to the realities of a current labor seller’s market. Workers, meanwhile, are paying with more sweat, but also find themselves freer to press for more money or scout for new opportunities that emerge in a market more favorable to workers. Given those conditions, the question that looms even more prominently today: How content are people with what they do for a living, all things considered, and how might the current work environment and its many cross currents be shaping that assessment?

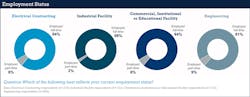

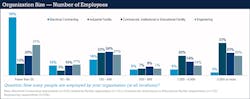

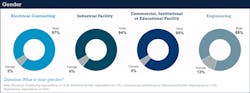

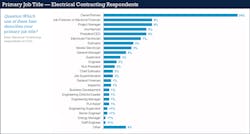

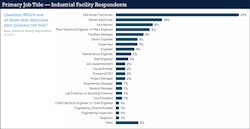

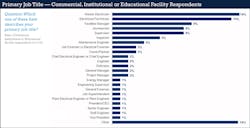

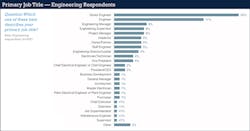

EC&M sought answers to these questions, and a host of others related to employment in the electrical field, in a recent survey of more than 800 electrical professionals. The first-ever Informa Engage Salary Survey 2019 (based on 2018 salaries) queried employees, nearly all full-time (Fig. 1), of electrical contracting firms, engineering companies, industrial facilities, and commercial/institutional/educational (CIE) facilities of various sizes (Fig. 2), seeking insights into both compensation and job satisfaction. More than 30 job titles — the majority of which were held by male employees (Fig. 3) — are represented in the respondent sample, but engineers, electricians and owner/partners together make up about 37% of it.

The picture that emerges is one of a broad electrical professional workforce that is largely well compensated by national standards, broadly educated and professionally challenged, and seemingly happy in their work. But it’s also one that may be feeling the strain of job and career demands and uncertainties about the overall economy and its potential impact on their jobs and companies that employ them.

Pay Outpaces Averages

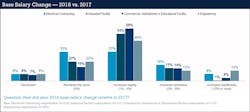

The financial reward for having a job in the electrical field today — in a period of strong economic growth, full employment, and a robust construction economy — looks to be ample, if not gleaming. The survey reveals that average 2018 base salary for electrical professionals in the sample calculated to nearly $88,000. Of the four employment categories surveyed, the highest base was in the engineering sector, coming in at $103,985. The lowest was in the CIE category, where the mean was $77,155, while electrical contracting ($87,588) and industrial facility ($82,185) were sandwiched in between (Fig. 4).

Reported engineering base pay figures relate heavily to those identifying as engineers as opposed to various business management positions; 40% were either staff or senior engineers. Of CIE sector respondents, roughly a quarter identified as master electrician or electrician/technician, mirroring the sample in the industrial facility category. Among electrical contractors responding, owner/partners were the biggest, at one-quarter of the sample (Fig. 5 through Fig. 8).

Ken Simonson, chief economist with Associated General Contractors of America (AGC), describes an “acute shortage” of hourly craft workers, along with growing tariffs on materials, as being responsible for driving construction costs steadily higher.

“An AGC/Autodesk survey this summer found nearly 80% of nearly 2,000 responding contractors reported difficulty filling hourly craft positions, and 57% reported the same for salaried positions,” he says. “Nearly as many firms expect the difficulties to remain or intensify over the coming year.”

That’s translating, expectedly, to higher wages. Simonson says two-thirds of firms surveyed reported higher base pay rates for employees and growing recruitment, training, and overtime costs. That’s leading to higher bid or contract prices (44% agreeing) and the need to quote longer lead times (29%). AGC says higher pay is one factor in the past year’s 5.6% increase in the BLS’ Producer Price Index for new, repair and maintenance work performed by electrical contractors. That index has advanced 14% in three years.

Labor pressures are compounded by the robust construction economy. AGC says there were 373,000 job openings in construction as of late July, the highest it has recorded. Still, 442,000 workers were hired in the sector that month, the second highest number since 2008, but a near all-time high quit rate of 2.8% kept contractors scrambling. It all adds up to contractors facing “challenges in finding and retaining acceptable workers to hire,” Simonson says.

Pay Boosts Vary

AGC is mostly referencing a craft worker challenge, but it’s a safe bet that other job categories at contractors are also stressed to some degree by the same factors. The same holds true for service contractors and other companies employing a broad range of electrical professionals. That’s evident with the EC&M survey finding that compensation (both base pay and bonuses) has been and could well continue rising.

Reported base pay in 2019 increased over 2018 in three employer categories and was virtually unchanged in one other, the survey found (Fig. 4 and Fig. 11). In some categories, average pay boosts are higher than the BLS estimate that average hourly earnings of U.S. workers rose 3.2% between August 2018 and August 2019, and in others lower. The mean base pay for electrical contractor workers in the sample rose 2.3%, from $87,588 to $89,582. But base pay for engineering firm workers stayed constant, the mean remaining at almost $104,000, perhaps a reflection of that sector’s increased reliance on bonuses in a period of strong revenue and profit growth. On the top end, the mean for industrial facility electrical professionals rose 5.6%, from $82,185 to $86,817, indicative perhaps of a resurgence of the nation’s industrial sector and the need for more workers. Mean base bay for employees at CIE companies rose 2.4%, from $77,155 to $78,981.

The 2018 to 2019 base pay differentials strayed somewhat from the pay adjustments respondents recalled getting between 2017 and 2018 (Fig. 12). The average reported pay hike for electrical contractor employees between those years was 2.6%. That was slightly higher than the 2.3% average difference between reported base pay in 2018 and 2019. The average hike for industrial facility workers was much lower, though, 1.8% higher compared with the category’s 5.6% average change for 2018-2019. By contrast, the average pay hike last year in the engineering sector was 2.6%, while it was unchanged this year. The CIE sector average hike was 2.5% a year ago, in line with this year’s average reported base pay change of 2.4%.

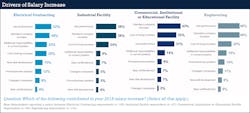

Electrical professionals who got base pay boosts in 2018 — 59% of electrical contractor employees, 70% of industrial employees, 77% of CIE staffers, and 70% in the engineering space — cite a host of reasons, ones that presumably affected the magnitude. Tops among them were job performance, standard company increase, cost of living and added job responsibilities in current position (Fig. 13). Notable was that electrical contractor workers reported added responsibilities at a higher rate than other professionals, suggesting contractors are expanding services or squeezed enough on labor to require more cross-training and multi-tasking. More engineering pros, meanwhile, cited job performance and standard increases as reasons.

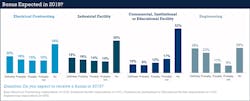

Bonuses Reflect Boom

Not surprisingly in a strong economy, bonuses are likely becoming a bigger part of the compensation puzzle for companies. With more business coming in the door, organizations are more inclined to share the winnings, especially with workers who directly contributed or are otherwise valuable and may be at risk of leaving for greener pastures. No matter how they are structured or awarded, bonuses look to be a component of how companies are compensating electrical professionals. Last year, the survey found, bonuses went to 55% of respondents in the engineering segment, while 40% of electrical contractor employees got one. Just 29% in the CIE sector received a bonus, but 43% of industrial facility workers were rewarded (Fig. 14). Looking ahead to the coming year-end, a good share of respondents has some expectation of a salary padding, ranging from a high of 71% in engineering to a low of 48% in CIE (Fig. 15).

If the economy continues to hum along and full employment continues, electrical professionals, like other workers, will almost surely continue to prosper. If their jobs are linked to the construction economy, which is growing but starting to show cracks in some areas, prospects for wage hikes and bonuses look to be even firmer. On the other side of the ledger, their employers, electrical contractors and engineers will face more challenges in trying to figure out how much to pay, how to pay, and who to reward, knowing good times can be fleeting.

“Compared to other industries, construction continues to lead the pack in terms of pay increases,” says Jeff Robinson, president of PAS, Inc., a Saline, Mich.-based company that follows construction industry compensation trends. “The last year or two we’ve seen more behind-the-scenes, midyear catch-up increases in the sector, which could bring the average pay hike by year-end up to a range of 3.6% to 3.9%.”

Construction Wages Higher

In its June 2019 Construction Compensation Quarterly, PAS cited WorldAtWork’s estimate that exempt professionals nationally saw 3.1% wage gains in 2018 and were on track for 3.2% increases in 2019. However, it saw hikes of 3.5% for construction sector exempt staff in 2018 and 3.8% this year. By comparison, PAS’ research pegged actual construction/construction manager staff average gains at 3.7% last year.

Contractors are feeling compensation pressure at many job levels, Robinson says, from electricians and supervisors to project managers and engineers — basically anyone who plays a role in handling the growing volume of business that demands full staffing. More have been responding with bonuses for key workers partly to avoid getting trapped by higher wages that might be harder to pay if business scales back. In addition, bonuses may be helping keep older staffers contemplating retirement in the fray.

“Bonuses were flat for a number of years after about 2012, stagnating or going down, but all of a sudden in 2017 or so they bounced back,” Robinson says. “The last four years we’ve seen larger bonuses. But when the economy or margins turn down, that variable pay will go down, too.”

One respondent, David Burkhart, president of Gillespie Electric, Inc., East Greenville, Pa., says he’s had to raise compensation beyond standard increases for workers thought more likely to leave for higher pay. More are in that category as busy competitors try to poach, and some have been leaving. He says pay has been raised for middle-level workers, overtime is padding paychecks, and more bonus money is on the table as a reward for performance and incentive to not jump ship.

“Labor costs are going up, and we’ve had to be more selective on jobs because of manpower issues,” Burkhart says. “You can’t bid assuming you’ll be able to find enough labor. Labor costs as a percentage of a job have inched up from 50% to 55% to 55% to 60%.”

Another respondent, a unionized electrical foreman for an electrical contractor, who reports his base salary as $98,000, rates his overall compensation package as “good,” receiving small increases about every six months per the union contract as well as the occasional bonus.

For a 28-year-old trained electrician who also performs technician duties for an industrial facility where he’s been employed three months, a $56,600 salary is adequate but leaves him feeling somewhat underpaid.

“I look into this pay issue fairly often, and I think I’m below normal for what I do,” says the unionized worker. “The electrical aspect of the job is much more technical and covers a pretty wide gamut.”

Another respondent, a middle-aged electrical engineer employed by a firm with 5,000+ employees, says his last pay boost was between 6% and 9% — enough to keep him mostly satisfied with his job, which he’s had for five years. The company has a limited bonus program that he’s benefited from sporadically, but it’s rarely been significant. His compensation package and other factors, he says, keep him from entertaining head-hunter inquiries that now come almost weekly.

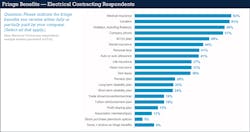

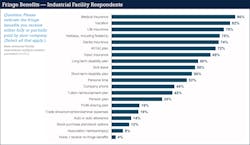

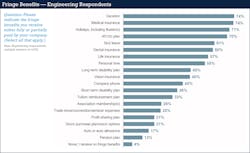

A solid benefits package — one that’s gotten more complex and expensive with medical insurance but also more diverse with company stock purchase deals and financial wellness coaching — keeps the engineer content as well. Indeed, fringe benefits have become central compensation components and were cited by many survey respondents as being at least fairly available and comprehensive.

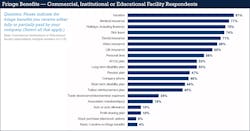

Medical insurance, paid time off, and 401(k) plans were the most frequently mentioned available benefits, though a list of 19 other common ones got a fair number of mentions, depending on employer type. The most thorough benefits packages appear to be offered at industrial facility and CIE companies, with engineering firms slightly below. Benefits packages offered by electrical contractors and available to respondents appear to be the least generous in terms of scope (Fig. 16 through Fig. 19).

By any reasonable standard, electrical professionals as a group can’t really gripe about compensation; wages exceed key national averages, and many of their employers appear to be in line with standards on fringe benefits. On that measure, they should feel satisfied with their jobs. But that’s only one, and the survey findings suggest that other factors stop many individuals short of saying, like so many other workers today in other jobs, “I can’t complain.”

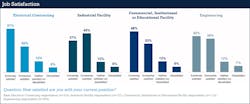

Only about half of all those polled would fall into that camp, but the numbers saying they were “extremely satisfied” with their current positions varied — from a high of 51% of electrical contractor workers to a low of 37% of industrial facility electrical professionals. The contractor number could be an outlier because that category includes a higher share — 24% of owner/partners than the others (Fig. 20).

It’s noteworthy, though, that only about 6% of respondents say they’re unsatisfied. If “extremely satisfied” essentially means “satisfied,” and “somewhat satisfied” responses aren’t counted, then electrical professionals as a group are about as content with their work lives as most others. The Conference Board’s most recent job satisfaction survey finds 54% of U.S. employees are satisfied with their employment.

A sampling of explanations for being satisfied or not indicate compensation is only part of the story. Of about three dozen respondents who offered reasons for their answer, only six referenced money. Many of the rest addressed positives like responsibility, autonomy, the chance to learn, coworkers, and empowerment.

A 60-year-old environmental safety and health manager who recently moved from a CIE facilities management post with electrical infrastructure-related duties says he’s extremely satisfied because he’s working to protect employees.

“I like the least having to spend so much time doing paperwork, sitting in front of a computer,” he says. “I’d rather be out in the field more.”

Burkhart, who’s likewise extremely satisfied, senses his workers’ satisfaction is being tested by the pace of work. “Every job is a rush, it seems, but it’s a sign of the times because there’s so much work.”

The electrical foreman employed by a contractor said he’s somewhat satisfied with his job, wishing worker safety was a higher priority. From his perch as an IBEW apprentice safety instructor, he senses there’s a safety gap.

“Training isn’t happening enough now,” he says. “I don’t feel unsafe myself, but I see other workers doing unsafe things.”

The engineer is semi-satisfied with his position, content with his duties and compensation that allow him ample free time and don’t make him long for a promotion to management. One complaint: the company’s ever-changing health insurance plans.

Certainly, job satisfaction is a function of what one provides and what it demands, and how that balances out to impact the worker’s entire life. Certain key measures — ranging from the larger meaning a job may provide to support employers offer to the reasonableness of demands — get to the essence of job satisfaction.

Rating the Intangibles

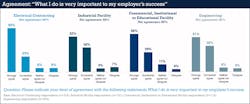

In terms of feeling like their jobs are important and meaningful, most electrical professionals are in agreement. Nearly 90% of those polled sense their jobs have some impact on their employers’ success, with strong agreement among half or more, depending on the work category. Electrical contracting again stands out, likely a function of the high share of ownership responding (Fig. 21).

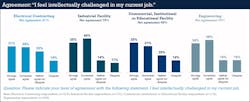

Jobs are also a source of personal fulfillment for many, a way to learn more and grow professionally and personally, and leverage it to their own benefit and that of employers and clients. That appears true among many electrical professionals; a majority of respondents say they feel intellectually challenged in their current job, with engineering and industrial facility employees agreeing the most (Fig. 22).

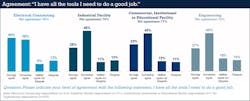

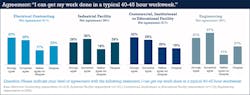

But people also need to feel their jobs are not overwhelming, that their employers are giving them the things they need to be successful in their work, and that they’re sensitive to the fact they have a life outside of work. On those scores, respondents have mixed feelings. A solid majority say their employers equip them to do good work. Across the categories, about three-quarters agree they have the tools needed to do a good job (Fig. 23). More broadly, that could also mean they have the education, experience, and knowledge (attained on their own) to achieve that goal. But only about one-third of respondents strongly agree they can get their work done in a standard 40- to 45-hour workweek, though many more somewhat agreed (Fig. 24). Yet 18% to 26% say that definitely is not the case, suggesting a fair number think their jobs are rather demanding — maybe too much so.

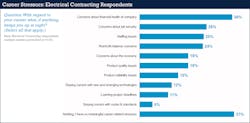

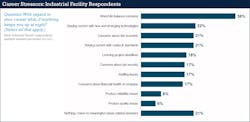

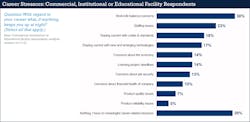

Living to work instead of working to live may be a sign of our busy, overscheduled times, but many workers are smart enough to know when something’s out of kilter. When asked “what keeps them up at night about their careers, “work-life balance concerns” topped a list of 10 career stressors for three of four employer categories, with engineering firm employees mentioning it the most as the top source of stress. Electrical contractor employees mentioned it the least, with the most mentions going to “concerns about the company’s financial health.” Some, though, say their work is mostly stress-free. From 16% to 37% checked none listed, saying instead they had no significant job stresses (Fig. 25 through Fig. 28).

All things considered — compensation, challenge, time demands, meaningfulness, and other factors — electrical professionals seem to conclude that it’s all worth it, that they’ve chosen the right career, and that, despite drawbacks and downsides, their work is satisfying. One measure of that, generally, is whether people would steer someone close to them into the career they’ve chosen (Fig. 29). For almost half of electrical professionals, the answer is a full-throated “yes,” that they’d strongly recommend the electrical field to their children or other close relative. Add in those who might qualify the recommendation some, and the majority seem to say it’s a field worth pursuing today.

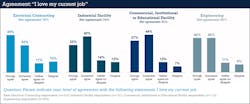

But the real measure of job satisfaction may come down to the L word — how many are willing to say they love what they do (Fig. 30). On that score, almost 40% of respondents strongly concur with the statement: “I love my current job,” with the most in agreement being on electrical contractor payrolls and the fewest being industrial facility professionals. If there’s such a thing as lukewarm love, the number spikes; another 32% to 44% somewhat agree they love their jobs. Only 7% to 13% disagree.

Though there’s far unanimity among the ranks of workers in the electrical field, many today are clearly content. Examined in a period of low unemployment, a strong economy, rising wages, and soaring demand for construction-related projects, the electrical professional sector today is populated by workers who, by all appearances, are valued, hard-working, and committed. That’s tenuous, though, and if the field’s fortunes decline with a slip in the economy, the next Informa/Engage survey could well reveal a vastly different picture.

Sidebar: Satisfaction Guaranteed?

Responses to EC&M’s recent salary survey ran the gamut, with some respondents reporting being satisfied, miserable, and everything in between when it comes to their jobs. Here’s how some answered when asked directly, “How satisfied are you with your current position?”

• Work is fun!

• Good to be king.

• Wider range of projects, supportive coworkers/team, more pay and less office/company BS.

• I like making things better than they were, and my position allows me to make the training material better for the instructors and students.

• I enjoy what I do.

• I’m my own boss.

• I love my job. It can be stressful at times, but I work with great people and have the freedom to make mistakes and learn from them.

• 40-hour workweek with great benefits.

• Great company with opportunities to grow.

• I am fully able to use may education and experience in building a leading firm operating in the U.S., including effective use of employees, minimizing COGS, maximizing margins and offering solutions well in advance of leading, often much larger, competitors.

• Great company!

• I went from nine years as a contractor with good pay but marginal benefits and lots of overtime to an in-house position at a public agency with great pay, only 40 hours a week and great benefits.

• Terrible pay, lack of knowledgeable employees.

• No increase in salary.

• Because I’m in a union that gets me the best compensation package.

• Shift work is terrible.

• Work for good people and good bosses and have great employees.

• I'm doing what makes me feel good as I contribute to the betterment of the company.

• Great people, fairly clean work environment.

• I have been fairly compensated for all work performed.

• I have a better academic formation for what I am doing now.

• I am trusted and respected.

• Challenging, outstanding leadership team.

• I report directly to a VP and have almost total autonomy as well.

• Self-employed and enjoy training in the electrical field.

• Old age discrimination. Am being forced out this year on largely those terms.

• Exciting opportunities abound.

• Enjoy the job with the customers.

• My boss is one of the most excellent people I've ever worked for in terms of leadership and business sense.

• No travel, home every night.