A stew of knotty issues is sparking fresh debate over whether swimming pools adequately protect users from the menace of electric shock. Leading the way is a flurry of publicity about deadly and injurious encounters with stray electricity around the structures, rekindling a fear that seems to bubble to the surface with clocklike regularity.

Aging pools — and the risks they carry in the form of degraded or outdated infrastructures — compound those concerns. Add in lingering questions about the qualifications of installers and inspectors, calls for tighter regulations/new safety standards, and the rise of new technologies, and it’s clear that pool electrical issues are getting more attention.

The core concern is whether more pool structures (existing and newly built) are slipping into the danger zone. The adequacy, functionality, and reliability of essential protections against the risks posed by an environment where water and electrical current must coexist in close proximity — chiefly equipotential bonding and grounding systems — are coming under increasing scrutiny.

Tragedy strikes again

Those persistent concerns were stoked this summer by the electrocution of a 7-year-old Florida boy, which followed an incident last summer that saw a man electrocuted in a Houston hotel pool.

According to news reports, the boy, Calder Sloan, was swimming in the pool at the family’s Miami home when he was thrown from the pool and knocked unconscious. Investigators believe the pool water became electrically charged when current entered through a light fixture in the in-ground pool. They reportedly discovered that a ground wire wasn’t attached to the transformer, opening the way for 120V to energize the light casing, allowing electricity into the pool water.

The boy’s death spawned a wrongful death lawsuit that names, among others, a Miami electrical contractor reportedly hired soon before the incident to perform electrical maintenance on the pool. Brought by Colson Hicks Eidson, Coral Gables, Fla., the suit alleges Gary B Electric & Construction failed to “use reasonable care in the inspection, installation, and repair of the home’s electrical components, including the installation of the new electrical panels and the pool pump’s grounding rod and removal of the pool deck’s pole light, to ensure the electrical system was properly grounded and bonded.”

Electricians also were implicated in the Houston incident, in which a 27-year-old man was electrocuted while coming to the aid of a child who was struggling in water that had been delivering shocks to other swimmers moments before. According to media reports, two employees of Brown Electric, Inc., a Houston-area contractor that had been hired by the hotel to perform pool bonding and wiring work were charged with criminally negligent homicide after an investigation found that wiring to the pool light lacked a GFCI device, setting up conditions for current to flow into the pool water. It’s also alleged that the company did not secure a permit to perform the work.

Searching for answers

While the root causes of both electrocutions may prove to be different — and remain to be clarified within a legal framework — the incidents appear similar in one respect: They point to a likely blend of negligence, incompetence, and ignorance — a potentially lethal combination when working with a pool’s electrical infrastructure. In a larger sense, the electrocutions serve as a reminder of what’s at stake when pools are designed, installed, and maintained — not to mention the need for safe components, competent personnel, and routine maintenance.

That message has seemingly been heard in Florida. The governing body of the county in which the 7-year-old boy died has been moving ahead with controversial legislation addressing one aspect of that tragedy.

The Miami-Dade Commission gave its early backing to a law that would require any lighting installed in and around newly installed or improved private swimming pools to be of the low-voltage/transformer variety, extending the scope of a requirement that exists for commercial pools in the county. Even though the Sloan pool apparently had such lighting — and the accident appears tied to human error and faulty wiring of the system that uses a transformer to step down 120V to a fraction of that to power lights — the incident reignited a long-simmering debate in the state over pool safety requirements and what can/should be done from a public policy perspective.

A tireless advocate of stronger regulations on pool lighting, Irv Chazen, owner of Custom Pools, a Miami pool installer, and an official with Associated Swimming Pool Industries of Florida, applauded the commission’s action, saying the boy’s death should offer an unequivocal answer to the question of “why have two standards; why not carry the same mandatory requirement to install low-voltage lighting and transformers to family pools?”

Caution urged

But other pool installer interests greeted the push for new regulation, which had expanded in August to Palm Beach County, Fla., with calls for caution. In light of the electrocution tragedies, The Association of Pool & Spa Professionals (APSP) instead emphasized the need for more vigilance in inspecting and maintaining pools, stopping short of endorsing any kind of blanket requirement for low-voltage lighting.

Carvin DiGiovanni, the association’s senior director, technical and standards, says the incidents point to a clear need for pool owners to better monitor and inspect aging pools and to ensure that maintenance is performed by competent professionals. However, he worries that more stringent lighting requirements, while appealing when framed as “low-voltage” solutions, could end up stifling the search for new solutions at a time of surging innovations in new pool lighting delivering better safety, performance, and aesthetics.

“I think we need to be careful that we don’t lock into something on low-voltage that could minimize the chances for new lighting technologies that may require higher voltage, augmented with different processes that lead to safer lighting,” says DiGiovanni. “There’s still a school of thought that questions whether low-voltage will solve the safety problems.”

But low-voltage lighting in and around pools is growing more popular, a trend progressively reflected in the National Electrical Code (NEC). The 2011 NEC established a “low-voltage contact limit,” an acknowledgement of the surging popularity of pool lighting and the need to spell out safety parameters, product specifications and installation and configuration guidelines for emerging low-voltage alternatives. Restrictions on such lighting are relaxed in the 2014 NEC; low-voltage luminaires that don’t require grounding no longer have to be placed a minimum of 5 feet from a pool’s inside walls.

Beyond lighting

Even as forms of potentially safer lighting emerge, many aging pools remain tied to 120V lighting systems that themselves are aging, often in concert with GFCI protection and pool bonding systems essential to pool electrical safety. The condition and operability of those systems, according to Code experts and electrical contractors who install and maintain pools, is the real concern when it comes to pool safety. If compromised, that can neutralize any margin of safety offered by low-voltage lighting.

Underwater lighting systems do pose a clear threat because corroded and faulty fixtures can become electrodes for introducing current into water, says pool electrical systems expert Bill Hamilton, III, president of Hamilton Associates, a Pflugerville, Texas engineering services firm. But the root cause of most shocking incidents, says the member of NEC Code-Making Panel No. 17 (CMP 17) representing APSP that oversees Art. 680 covering pool structures, often lies with systems that are supposed to form a barrier to electric current ever posing a lethal threat.

“Almost inevitably,” he says, incidents he’s investigated where shocks have been traceable to light fixtures “involve non-existent, faulty, or deteriorated grounding and bonding systems in concert with that.”

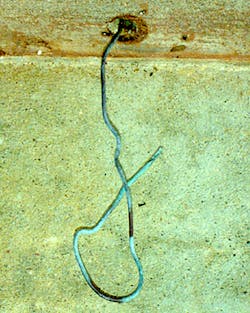

Through the years, the Code has been revised to better define the proper design of pool equipotential bonding and grounding systems, which must remain operational over the course of many years. Following and maintaining those guidelines is essential, Hamilton says, both in the installation of new pools and the ongoing servicing required of pools as they age. Most critical is the equipotential bonding grid, consisting of copper-wire connections to metal components in and around the pool, which equalizes voltage and lowers the risk of electric shock.

CMP 17 addressed bonding again in the 2014 Edition of the Code. Concerned that wording referencing the “bonding of pool water,” was confusing, the panel revised Sec. 680.26. It now states that “pool water must have an electrical connection” to specific bonded parts, or “the water must be in contact with a corrosion-resistant surface that’s at least 9-square inches.” A new requirement to ensure functionality is that the item making contact with the water must be “in an area where it won’t be dislodged or damaged… .”

Knowledge and competence gap?

Despite efforts to make pool bonding and other key elements of pool electrical systems more understandable, some see stubborn confusion about how it’s actually done. That’s putting not only newly installed pools at risk, but also older pools whose bonding grids can deteriorate over time and may require refurbishing or repairing. As the recent shocking and electrocution incidents suggest, there’s no certainty that every pool installer or the electrical contractors they typically sub work out to fully understand the nuances of pool bonding or grounding — or that they can be trusted to perform the work by the book.

In his years as an electrical and building code enforcement officer for the town of Ithaca, N.Y., Chas Bruner has witnessed a less-than-ideal grasp of the bonding concept, in particular. That’s compounded by installers who sometimes choose not to hire electrical specialists to do the work, a byproduct of comparatively loose state regulations on employing licensed electricians.

“Some people aren’t trained, and, in a lot of cases, you have college kids doing the installations,” he says. “So you end up counting on seeing some pretty flimsy bonds and since there can be a lot of different pool designs, it can be hard to see if they’ve selected the right way of doing it.”

Install jobs can be difficult to thoroughly inspect as well, he says, because the perimeter bonding is quickly covered with concrete in fast-paced jobs. “You have to get there quickly,” he says. “I’ve had concrete trucks ready to pour, waiting for me to give the OK. In some cases, I’ve had to hold them up.”

Time takes its toll

Even if they’re installed properly — and that’s hardly guaranteed if work is governed by outdated versions of the NEC — pool bonding and grounding systems are subject to wear and tear. Over time, these systems can and do corrode, and a host of variables can affect the pace of decline. That fact heightens the importance of, as the pool group APSP advises, “inspection, detection and correction” to address things like “aging electrical wiring, the use of sump pumps and vacuums that are not grounded and lack of proper bonding.”

Triec Electrical Services, Springfield, Ohio, has heeded that call. Motivated partly by news of pool electrocutions, Owner Scott Yeazell says he’s recently begun offering complimentary inspection and testing of pool bonding. He suspects there are enough degraded systems in existence that repair work will provide the payback. He’s eager to step in because he knows vigilance can be the difference between life and death.

“Bonding is your secure backup. If it’s gone and you don’t know it, you’re at risk,” he says. “But I don’t see any program or commonly accepted practice of testing bonding to see if it’s intact or not.”

Hamilton, who senses that bonding still “mystifies” many pool owners and electrical contractors, says he’s been an advocate of making inspections of both bonding and grounding systems a requirement. He has helped pioneer techniques and protocols to test systems, some of which have been referenced in a handful of states that have instituted mandatory commercial pool testing.

Right the first time

While maintenance and testing is important, Hamilton says safety starts with the initial installation. Installers must adhere to the up-to-date Code, he says, which should be incorporated into local ordinances. But bonding system design should be flexible to a degree, adapted to geographic variables like the water table and soil type, which can affect their functionality, and longevity.

“Pools are only as safe as they get built,” he says. “But then they need to be maintained, and today there are a lot of 50-year-old pools out there.”

While the recent focus on pool lighting is well justified, it’s important to remember, he adds, that the pool electrical safety issue is multi-faceted.

“If you make a statement that says were going to have safe pools if we convert everything to 12V lights, that’s a highly oversimplified statement that doesn’t reflect the physics of what goes on with electricity in a pool,” he says. “If it were as simple as that, then (NEC) Art. 680 (covering pools) would be one sentence: ‘Put a 12V light in your pool. Thank you.’”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR 1: Low-Voltage Lighting Steps into the Limelight

In addition to traditional low-voltage incandescent lighting, new and improved lighting technologies are becoming acceptable options. Lighting, in turn, is poised to become safer and more functional, versatile, and dynamic.

“Because of changes in technology, consumers have more lighting choices than ever,” says Carvin DiGiovanni, senior director, technical and standards, for the Association of Pool & Spa Professionals. “Options include LED, fiber optics, as well as different incandescent lighting.”

While traditional 120V lighting is still the dominant and preferred type — both for its cost and performance — low-voltage is catching on because it’s delivering a package of new solutions. New UL-listed products are coming to market that conform to low-voltage lighting standards in the NEC, and many don’t require grounding because they’re sealed in plastic.

“There’s a lot of amazing, all solid-state stuff being manufactured now that would never have been allowed at 120V,” says Bill Hamilton, III, a pool electrical expert and president of Hamilton Associates. “Some of it is microprocessor driven, allowing you to put on a real light show.”

But new generations of safer and more functional lighting also incorporate new technologies that aren’t yet fully understood in the field. Although the Code has evolved to address low-voltage, some low-voltage installations lie outside traditional interpretations.

“Some of this new high-tech lighting can have some very sophisticated power supplies,” Hamilton says. “That was recognized in the 2011 Code cycle, and we’re still working with authorities having jurisdiction to get them to bring local ordinances regulating low-voltage lighting into line with some of these new technologies.

“We don’t want them red-tagging installations that would actually be desirable in terms of low-voltage alternatives. If you say you’re not going to allow anything but a 15VAC light or below, you may be excluding a whole category of brand new solutions that may be very desirable and could be a lot safer.”

The transition to these new technologies is being aided by new ways of defining acceptable pool lighting. Hamilton notes new pool and spa industry code language that sets a clearer, more objective standard for determining minimum pool illumination requirements. Along with an industry push to use a lumens rather than a wattage standard to categorize lighting and better guide how lighting is best deployed, the effort could further set the stage for the deployment of more low-voltage lighting in pools.

“Technology, because of a number of factors, is tending to move in a direction that’s going to provide inherently safer devices just because they’re getting away from 120V and getting into fairly low-voltage, reasonably low-current solutions, compared to incandescent lights,” he says.

SIDEBAR 2: In the News and On the Web

EC&M has reported on several stories recently that relate to the hazards electricity presents in pool applications. Read these and other full news reports at ecmweb.com.

Pool Repairman Dies in Suspected Electrocution in Florida

This worker died from a suspected electrocution in Panama City Beach, Fla., when he and another coworker were repairing pool lights at a private residence. According to a report from the News Herald, one man was working at the breaker box while the other was in the pool when the accident occurred.

Pennsylvania Town Closes Pool After Shocks Reported

A town in Pennsylvania shut down its pool when a patron reported feeling electrical currents while sitting on the pool deck. The town council subsequently authorized $75,000 in emergency repairs after the incident. According to a report from Lehigh Valley Live, electrical engineers said the pool deck was improperly bonded.

Children Shocked in Public Pool in Philadelphia

After three children were shocked in a public swimming pool in Philadelphia, local news sources said that area residents had been reporting for the past month a sensation of tingling or “pins and needles” when swimming. The pool was closed indefinitely, and the Philadelphia fire executive chief said an equipment malfunction could have caused the current.

Three Children Shocked at Florida Condo Pool

Three children were shocked at Florida condominium community pool as a result of shoddy electrical work. The children spent several nights in the hospital after being shocked at the Palm West Condo pool in Hialeah. According to a report on Local10.com, a green ground wire on the pool pump was disconnected. The building inspectors’ report said that when the pump malfunctioned, the electricity wasn’t directed into the ground. Instead, it energized the water the pump was pushing back into the pool. To see police photos, visit http://bit.ly/1rlBZSJ.