Near-miss reporting — a workplace injury-prevention tool steadily gaining more credence — poses a conundrum of sorts. Up to a point, perhaps, you might think the more of it the better, but eventually you want to start seeing less.

That’s the curious nature of documenting situations in which workers engaged in a task and escaped injury because they were lucky, well-trained, observant, or all of the above. More of such reports can signal a diligent safety culture. It can also mean the workplace is riddled with safety hazards — or a little of both.

The interpretation challenge was illustrated at a Nucor Steel Co. safety meeting a few years ago, recalls Joe Rachford, an electrical engineer at Nucor Steel Gallatin, Gallatin, Tenn. Addressing the gathering, he says, the company president voiced concern about the falling volume of near-miss reports. Subscribing to the theory that more is better, the executive was worried about flagging vigilance. But, as it happened, the company had actually turned a corner.

“We went back, looked at the data, and found that what was truly going on was that our focus on safety had led to more people doing things correctly — so there were fewer reports,” says Rachford, noting investigators deduced that fewer near misses was largely a function of fewer recordable injuries because there’s demonstrated linkage. “We were starting to see the fruits of all the work we had put into improving safety.”

But Nucor management was on the right track. It had fully embraced what many companies may struggle to understand — as a rule, near-miss reports are a strong sign that safety is being taken seriously by workers, whose knowledge, training, and observation skills are the last line of defense against injury.

“Management is used to driving numbers low, but with near misses, you really want more,” says Lanny Floyd, partner/principal consultant with Electrical Safety Group, Inc., Elkton, Md.

It’s hard to gauge if, in fact, more organizations today are heeding that message. What’s more clear, though, is that safety experts like Floyd continue to harp on the importance of near-miss reporting as a core element of workplace safety enhancement.

A unique risk profile

That may be particularly true in the electrical realm, where everyday hazards carry potentially grave consequences. The odds of being seriously injured or killed when encountering unsafe conditions in the electrical environment may far exceed those for other classes of occupational injuries.

“Electrical injuries account for less than 0.2% of all injuries in the workplace, but they have very high severity potential,” says Floyd. “One in 13 of the lost-time injuries from electrical contact are fatal, and injuries from arc flash burns and contact with high voltage have high likelihood of involving long-term hospitalization and long-term disability.”

Their rarity, however, can blind even the most fastidious occupational safety experts to the need to carefully manage the risk — and that’s where near-miss reporting’s value becomes clear.

By training workers to spot electrical dangers and encouraging them to report minor injuries and even close encounters, safety teams can collect information on unsafe conditions or practices that could have led to serious injuries. Then, through careful documentation and study of incidents, safety managers can expose and address potent risks and hazards that can lie dormant until a severe injury or fatality occurs.

While incidents that result in injury or death can also be deconstructed to reduce hazards and better manage risk in the future, near-misses are particularly valuable. Because they’re chillingly frequent — on the order of 300,000 for every 300 recordable injuries — 30 lost-time injuries and one fatality according to a probability model known as “Heinrich’s Relationship,” they can constitute a steady stream of valuable condition information from the field. Plus, they come to light because workers were careful rather than because someone got hurt.

Thus, near-miss review programs, says Allison Haluik, an electrical engineer in the engineering department of ArcelorMittal Dofasco, a steel producer in Hamilton, Ontario, can help vividly illustrate dangers and get workers to take safety seriously and think before they act. Haluik, who recently presented a paper at the 2016 IEEE Industry Applications Society (IAS) Electrical Safety Workshop in Jacksonville, Fla., explained the importance of training the next generation of electrical safety workers to better manage risk perception. Papers presented at a succession of recent Electrical Safety Workshops like this one, sponsored annually by the IEEE Industry Applications Society (IAS), offer evidence that near-miss investigations can drive meaningful changes and improvements in electrical safety practices.

Haluik places a high value on getting workers engaged to spot electrical hazards that by their nature are hard to see. Both routine safety and reliable near-miss reporting, she says, depend on workers fighting the human tendency to make snap decisions solely on what’s in front of them and to instead take time to carefully evaluate risk before acting.

“It’s been said that good decisions come from experience — and that experience comes from making bad decisions,” she says. “The value of communicating all accidents, including near misses, is that people, in general, have difficulty recognizing hazards and imagining the possibilities of what could go wrong.”

Formalizing the process

But for electrical near-miss incidents to be fully leveraged to reduce hazard and risk, organizations must demonstrate commitment. Safety experts say it’s essential to foster a climate in which near misses are reliably recognized and consistently reported, incidents are thoroughly investigated, and findings are acted on and liberally shared. Near-miss reports become truly valuable when they’re evaluated in the aggregate and, over time, creating a big picture that can expose glaring gaps or trends in workplace safety.

A near-miss reporting challenge that companies wrestle with is the critical reliance on gaining the cooperation of those in the field. Workers must be sufficiently trained to recognize and know when to back away from potentially unsafe situations or tasks. In essence, they must know where the safe line is and be clear on what constitutes a reportable near miss. Then they must be convinced that reporting incidents is their responsibility and won’t lead to punishment. Workplace realities can make those conditions difficult to attain, but without them, a near-miss reporting program will be crippled.

It presents a unique challenge in the sense that the traditional management-employee dynamic has to change somewhat, says Shahid Jamil, an electrical engineer and electrical safety expert with BP America, Inc., Edmonton, Alberta. A confrontational environment, he says, must give way to one in which management clearly explains the value of reporting, and workers must be made to feel comfortable doing so.

“The worker has to be part of the equation and strongly encouraged to report and train on what to look for,” says Jamil. “I think we’re seeing more reporting because they’re getting more assurance that they won’t get penalized for doing so.”

But the transition from reporting to actionable information and meaningful changes is not always straightforward. To do it right, organizations have to approach near-miss incidents with the mind-set of a detective, gathering information from a range of sources and running down all possible theories for what practices, procedures, conditions, and personnel may bear responsibility. Investigations, experts say, should ideally track a formal process that produces a set of findings and recommendations or directives that aim to reduce the chances of a repeat incident.

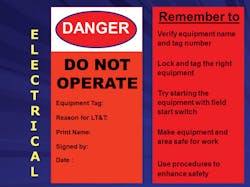

A recent near miss at Nucor, Rachford says, was investigated by a cross-departmental audit team. The team reviewed an incident in which workers preparing equipment for maintenance locked out the wrong 120V control circuit breaker, creating a potential shock hazard.

To understand how it happened, the team “walked the procedure down,” Rachford says, and verified that the fault didn’t lie with the written lockout sequence. Instead, the error resulted from the combination of an overly complacent worker misidentifying equipment that wasn’t marked as well as it could have been. The incident report resulted in changes to both equipment labeling and the lockout sequence that would make it harder for a worker to inadvertently select the wrong motor control center breaker.

The conclusions, Rachford says, were a good illustration of the value of taking a comprehensive approach to near-miss investigating. And they supported the theory that near misses and accidents don’t just materialize, but result instead from a cascade of missteps and conditions — a perfect storm that can and should be deconstructed.

“An accident is [the result of] typically anywhere from six to nine different sequences of events that happen to create the right circumstances,” he says. “If you stop any one of those, you won’t have the incident. And if you focus on the near misses, you can stop a bunch of them.”

Communicating conclusions

That’s contingent, however, on how the findings of near-miss investigations are handled. Value typically flows from a process that ensures formal reporting through appropriate channels and certain follow-up and corrective actions, experts say. While workplace safety is partially enhanced simply through the act of encouraging near-miss reporting, which leads to more vigilance, it’s greatly impacted when dangerous conditions, practices, and procedures are revealed and permanently corrected.

Electrical safety consultant Daryld Crow, owner of DRC Consulting, St. George, Utah, has seen near-miss investigations evolve. He notes they’re getting better, and there’s more accounting for how perceptions and biases can impact eyewitness reports to near misses. Properly investigated and disseminated, he says, they can help move the needle on safety.

“When they’re done in the spirit of fact-finding and not fault-finding, near-miss studies can produce important lessons and identify the root causes of an incident, and many times there are more than one,” says Crow.

There may even be an element of creativity that comes into play in how near-miss incidents are related to workers, who bear the brunt of both the risk from unsafe conditions and the responsibility of reporting. Floyd and other experts point to the need for relating near-misses as compelling stories rather than a dry recitation of facts. The more vividly near misses can be framed, the more likely workers are to see themselves as potential victims.

Floyd relates the story of a journeyman electrical worker speaking up at a company safety meeting where near misses were discussed in detail. It stuck with him, he says, because it’s a stark reminder that workers may face more day-to-day risk than we think because they haven’t been given the right mental tools to properly evaluate risks and hazards. More thoughtful near-miss reporting can help close that gap.

“He stood up and said, ‘I can honestly say that in my 25 years doing this work, I’ve never understood what the hazards are. I’ve been to training on the rules, what OSHA and NFPA says, what my company says about safety procedures, but I’ve never been trained on what the hazards are. These near-miss stories have helped me understand that I could have been the victim.’”

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].

SIDEBAR 1: The Case of the 4kV Motor Isolation Near Miss

Two qualified workers were assigned the task of isolating a motor starter ahead of the planned removal of a pump and motor for maintenance. The workers, who had prior experience doing such work, secured a permit and stopped the motor through its field stop switch.

But at the substation, the employee performing the work incorrectly racked out the wrong motor starter. Using appropriate arc flash and shock protection personal protective equipment (PPE), he then discharged and grounded the outgoing power cables, and installed locks and tags at the starter as part of the standard lockout/tagout process. The two workers then returned to the motor location and proceeded to disconnect the power cables to the motor designated for maintenance.

Not long after, an alert machinery worker noticed the mix-up and quickly informed both the two-man work crew and supervision. At this point, all work was stopped until the error was corrected. In addition, all electrical isolation tasks were suspended until all workers were made aware of the incident and went through full retraining in lockout, tagout (LOTO) procedures.

The follow-up investigation cited human factors as primary causes. Despite being fully qualified and trained in procedures, the two maintenance workers failed to correctly identify equipment. And they didn’t follow verification procedures that call for trying to start the motor before power cable disconnection. Fortunately, the machinery worker was alert and followed protocol in reporting what he found.

The near-miss investigation led to substantive changes designed to prevent a recurrence. For one, the incident itself was to be highlighted in re-training that emphasized the importance of verification. Also, LOTO was given a new name: LT&T, for Lock, Tag and Try. The Try step means to try starting the motor as the final step. New LT&T tags were developed for all trades, and FAQs were developed to clearly communicate the change to all personnel.

The investigation’s conclusion: “Human factors and failure to follow established procedures resulted in a serious near miss that had the potential for serious injuries or fatalities.”

This report illustrates several points common to near-misses. Authored by Shahid Jamil when he was employed as an electrical engineer for Exxon Mobil, the paper (A Serious Near Miss When Disconnecting a 4kV Motor, ©2011 IEEE), showed how a mix of inattention, misidentification, failure to follow procedures, unclear instructions, and also a dollop of vigilance, led to a near miss and its documentation.

SIDEBAR 2: Faulty Equipment, Poor Decisions Lead to Shock Incident

Another recent Electrical Safety Workshop paper discussed a more consequential near miss that highlighted the risks that can lurk in hurried work, improper training, and failure to thoroughly inspect equipment for sufficiency of design and application suitability.

Authored by Dan Doan, a principal consultant with DuPont Engineering, Investigation of a Near-Miss Shock Incident, ©2015 IEEE, this Electrical Safety Workshop paper spotlighted the case of a worker who was shocked after touching two control switches simultaneously on an outdoor temporary heating unit at a construction site. The worker recovered after being dazed and subsequently monitored at a hospital. But it was later determined electrocution could have occurred.

The follow-up revealed that the shock could have resulted from moisture in the switch conducting control voltage to external switch parts. After inspecting the equipment, investigators noted numerous design flaws that could have been responsible for creating that condition. The review found switches were not rated for outdoor installations, the enclosure was not rain-tight, and the control transformer secondary circuit was not fused.

Equally significant, it said, a post-delivery inspection could and should have revealed those flaws. Instead, the equipment, provided by a contracting company, was assumed to be safe and wired to a power source. A hurried work environment may have been responsible.

But worker missteps also contributed to the near-miss electrocution. The investigation revealed that workers sometimes cut corners and opened the heater unit’s control panel door to turn off and lock out the circuit breaker, when they should have done so at the feeding motor control center (MCC). Workers also failed to grasp the risk of exposure to 480V by entering a restricted approach boundary to turn off the internal switch.

The report spawned two important changes in procedures. Going forward, all pieces of equipment brought in as part of the maintenance project would be design-reviewed and inspected, and all non-electrical workers overseeing contractors working with equipment with electrical components would have to take a four-hour electrical awareness course.

About the Author

Tom Zind

Freelance Writer

Zind is a freelance writer based in Lee’s Summit, Mo. He can be reached at [email protected].