In 2009, Southern Company and Mississippi Power worked with the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) to launch an investigation into the use of LED technology for area lighting. The goal of the project, called the LED Street and Area Lighting Demonstration, was to discover a better street lighting fixture — one that not only meets the outdoor lighting requirements of consumers, but also uses less electricity. This case study discusses the results of Southern Company’s and Mississippi Power’s experience with this new technology, their expectations, and how the technology performed in the field.

Before Southern Company and Mississippi Power considered adopting LED lighting on a broad scale, objective metrics had to be drafted, measurement equipment had to be commissioned, and the pre-/post-measurement protocol had to be executed. EPRI worked with multiple manufacturers of LED lighting and tabulated specifications that were used to select one manufacturer’s equipment. Mississippi Power identified several sites and worked with Southern Company and EPRI to select the site best qualified based on the selection criteria. A successful site had to meet several criteria, such as a dedicated electrical circuit for all fixtures under test, minimal light trespass, and separation from trees that throw shadows upon the test area. Unlike a laboratory setup, it is often impossible to locate a perfect site, so some compromises were made.

The selected test method for field assessment was the pre-/post-test design, which involves measuring the power to and light output from existing HID lighting (called the baseline lights), swapping the existing lighting with LED lighting (called the treatment lights), and then measuring input power and light output from the new lights. This test method excludes potentially confounding factors, such as the environment and the orientation of lamp poles — factors that both baseline and treatment lights shared during the experiment.

One of the barriers to measuring light output was the amount of time required by an investigator to complete the measurements on a large parking lot or long street — a daunting task when executed manually. To be accurate and replicable, manual measurement of light required an investigator to operate within a grid, painstakingly measuring light in each cell — often while in uncomfortable positions. For the demonstration, and with funding provided in part by Southern Company, EPRI investigators designed a computer-controlled Mobile Light Measurement System (Scotty), a four-wheel, technology-laden, remotely controlled vehicle similar in appearance to the U.S. Mars Rover (Photo).

At the site selected for the LED demonstration, the light fixtures were mostly metal-halide (MH) models, which consumed about 222W each. Existing walkway lighting used mercury-vapor lamps that consumed either 120W or 72W, depending on placement along the walkway. The research team selected 12 LED fixtures rated at 115W for the parking lot. (Note that the original configuration of lights included only 11 fixtures — five poles with two fixtures per pole and one pole with only one fixture. An LED fixture was added to the odd pole.) The team also selected seven LED fixtures for the walkways, each rated at 60W.

Because of site damage from Hurricane Katrina, it was not possible to measure the pre-installation energy use of the walkway lighting. Photo 1 shows the light cast by the decorative LED fixture, with the decorative design emphasized in the inset photograph (taken in the daytime). For reference, an older style of fixture is shown further back and to the right of the LED fixture.

The main advantage of LED technology — that is, putting light only where it is needed — is lost in the decorative form factor. Photo 1 clearly shows the wasted energy in the form of light shining into the branches of the tree as well as glare, which is true of both technologies. It is because of this energy waste that the Department of Energy and its ENERGY STAR program have not created a category for the decorative form factor.

Photo 2 provides an approximation of the difference between the metal-halide (MH) lights and the retrofit LED lights for the parking lot. The photographs highlight the fact that although the illumination appears roughly equal, the LED lights consumed about 117W, whereas the MH lights consumed about 222W, a calculated power savings of 105W per fixture. The MH photograph was taken in the summer, and the LED photograph was taken in the winter, which explains the difference in grass color. The LED fixture has a higher color temperature than the MH, which is evident by the whiter, almost blue color emitted from the fixture. In addition to appearing whiter, the light output from the LED fixtures appears to be more even on the ground. This observation was verified by the photometric design received from the manufacturer and measurements taken by the Scotty. During 15 months of site monitoring, measurements taken by the Scotty indicated no significant degradation of the light level.

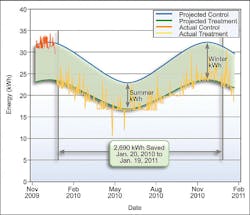

For the parking lot, energy was measured for 46 days for the baseline fixtures and 408 days for the treatment fixtures. The Figure illustrates both projected and actual energy use for each day over the course of the 15-month period of measurement. The yearly energy savings for the parking lot (Jan. 20, 2010, to Jan. 19, 2011) was approximately 26%. The data shown in the figure also indicates an opportunity for additional savings if improvements are made to the control circuit, such as simply positioning the photosensors that control the fixtures with a less obstructed access to the sky. Notice how the yellow trace (actual treatment energy) spikes above the green trace (projected treatment energy). Savings of up to 3% are possible if the lights are turned on and off in closer correlation to the hours of darkness.

At the time of this project, Southern Company and Mississippi Power discovered several disadvantages of LED lighting. These included a lower laboratory-tested efficacy than traditional HID lamps, lower immunity to electrical disturbances, less flexibility in replacing the LED light sources, and high cost of initial installation. Since completion of this project, the average efficiency of LED fixtures has improved, their cost has declined, and steps have been taken to improve immunity and serviceability.

During the investigation, advantages were discovered. Although the first cost for LED lighting is greater than the first cost for conventional lighting, the cost to maintain LED lighting is lower, largely because LED lamps last longer than HID lamps — a lifespan as much as 100,000 hr, according to some manufacturers. Second, the LED fixtures used at the parking lot require less cleaning than traditional HID fixtures (called “self-cleaning fixtures” by the manufacturer). Additionally, real-world energy savings — engendered by a shoebox fixture design that wastes very little light — offset the mediocre performance of the LED fixtures in the laboratory.

LED technology has now been deemed a viable high-efficiency lighting source for street and area lighting, but retrofitting poses an additional problem. The cost of retrofitting an existing fixture when the additional labor of rewiring is included can be just as costly as installing LED lights at new sites. But the end-users — nighttime pedestrians — win because of the nature of the light. Less light strays into unintended areas, and that light is a more pleasing white light compared to the yellow light of high-pressure sodium lamps.

The data from this case study indicates that LED light fixtures provide acceptable illumination and energy savings. However, saving energy is not necessarily the same as saving money. Many city engineers and politicians are surprised to learn that a 50% reduction in energy use does not typically equal a 50% reduction in the electricity bill. In fact, 15% is a more accurate number. Why? The other 35% covers infrastructure costs, such as pole and wire depreciation and maintenance. Because these costs are not vigorously publicized by vendors, care is required when calculating simple payback.

Many factors influence a decision to accept or reject LED lighting technologies, and authorities on the subject are neither vocal nor unified in their guidance. Standards for LEDs are evolving, and a consensus is developing for the proper application of LED technologies for outdoor lighting. Improvements in LEDs, optics, and control electronics continue, and fixture costs are continuing to decline. However, the tangled differences in light color and performance variables complicate direct comparison to traditional lighting technologies. The bottom line is that from a performance aspect, LED technologies are up to the task of replacing conventional lighting and saving a significant amount of energy. However, like many new technologies, the cost of retrofitting existing light fixtures — at least for now — remains a challenge.

Sharp is a senior technical leader and Geist is a senior project manager with EPRI, Palo Alto, Calif. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected].

SIDEBAR: Color Rendition: An Important Criterion for Lighting Technologies

Human eyes are designed for maximal vision in unobstructed daylight. In this so-called white light, both types of photoreceptors of the eye — called rods and cones — are active, accurately rendering the colors of objects. White light is actually a mix of different wavelengths in the visible spectrum. Perceiving such a light, our eyes average out all the different frequencies to arrive at a single color.

In search of daylight, manufacturers of outdoor LEDs coat each LED with a phosphor material to shift some of the stark blue light toward the yellow range, resulting in a broad-spectrum white light. However, white light doesn’t come cheap — the more phosphor a manufacturer uses to shift light, the greater the cost and the lower the LED efficiency.

The light output from an example LED lamp is continuous from 350 nm to more than 750 nm, whereas a typical high-pressure sodium (HPS) lamp emits a prominent yellow light, hampering accurate rendition of color.

In addition, this particular characteristic can also be shown using the correlated color temperature (CCT) index, which is used to grade the quality of light. Unobstructed daylight has a CCT of about 5,800K, which is within the range of LED fixtures in the marketplace. On the other hand, the light from an HPS lamp is in the orange range, once again hampering accurate color rendition.