The Latest on Light Pollution

Known as the “City of Light” in part for its early adoption of street lighting, Paris may soon be forced to darken the lights that illuminate those streets. Delphine Batho, the French Minister for Energy and Environment, recently unveiled a plan aimed to be a show of “sobriety” and to save the city money. Starting in July, commercial buildings and the lights on building facades will be turned off after 1 a.m., and interior lighting in office buildings will be required to be off an hour after the last employee leaves.

These lighting cutbacks don’t end with Paris, either. They’re meant to be applied throughout France. However, the biggest outcry against the proposal has come from Parisian merchants, who say the rule — in addition to bans on Sunday store openings and night shopping — will further hurt business at a time when the French economy has remained stagnant for almost a year, and unemployment has reached a 14-year high. They claim the dimmed lights will take away from Paris’ reputation as a welcoming shopping destination. Several large department stores are famous for their elaborate window displays that stay lit throughout the night.

But according to the Energy Ministry, the rule will merely align the commercial areas with operations of other institutions in the city. Currently, lights at more than 300 monuments, churches, statues, fountains, and bridges are already being turned off at night. For instance, the lights at the Eiffel Tower are turned off at 1 a.m. In the last 10 years, the illumination at Notre Dame has been brought down from 54,000W to 9,000W.

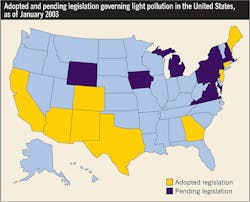

Many villages, towns, and cities across Europe — Berlin, Copenhagen — and in the United States — Tucson, Ariz., and San Diego — have already adopted lighting mandates (see Map). Although these laws vary considerably in language, technical quality, and stringency, their goals are similar. By turning off lights, adding lighting control capabilities, or retrofitting fixtures and lamps with more efficient technology, they help to save money and energy while reducing carbon emissions. Yet, what may be even more important is their ability to reduce light pollution.

Star wars

Light pollution is an unwanted consequence of outdoor lighting and includes such effects as sky glow, light trespass, and glare (see Light Pollution Glossary). The hazards of light pollution were first brought to the attention of the public in the 1970s when astronomers identified the loss of the night sky due to the increase in lighting associated with urban growth and suburban sprawl. In fact, the first lighting ordinance in the United States dates back to 1958 in Flagstaff, Ariz.

“The big push initially was astronomy,” says Scott Kardel, managing director of Tucson, Ariz.-based International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), which was formed in 1988 as the authoritative voice on light pollution. IDA educates lighting designers, manufacturers, technical committees, and the public about light pollution abatement in order to preserve the places that are naturally dark and improve the nighttime environment. “But we certainly see places where lighting ordinances come into play for a variety of other reasons. There are environmental causes behind these as well.”

In Florida, for example, many lighting ordinances have been put in place to protect the sea turtle population. Hatchling turtles, guided by an instinct to travel toward the brightest horizon (which used to be the light from the sky reflecting off the ocean), now often travel inland toward the artificial light, where they may die from dehydration, are preyed upon by fire ants and ghost crabs, or sometimes crawl onto the road where they are run over by cars.

“In the sea turtle areas, specific details as to the color light really matter because of their vision,” says Kardel. “Longer wavelength light — orange and red colors — is much less disruptive to sea turtles. Everywhere, the color and the quality of light do make a difference. Bright, white light is more damaging to the night sky and causes greater sky glow than other types.”

Light pollution can also affect human health. In 2009, the American Medical Association (AMA) became an ally of astronomers when it voted unanimously to recognize light pollution as a health hazard in Resolution 516: “Advocating and Support for Light Pollution Control Efforts and Glare Reduction for Both Public Safety and Energy Savings.” According to the resolution, light pollution can contribute to sleep deprivation and elevated stress levels. In addition, light glare can pose a safety hazard for night-time drivers. Furthermore, some studies show it may be linked to increased rates of cancer.

Through the resolution, the AMA advocates that all future outdoor lighting be of energy-efficient designs to reduce waste of energy and production of greenhouse gases that result from this wasted energy use; supports light pollution reduction efforts and glare reduction efforts at both the national and state levels; and encourages efforts to ensure all future streetlights be of a fully shielded design or similar non-glare design to improve the safety of our roadways for all, but especially for the vision impaired and older drivers.

Brighter isn’t always better

In the United States, it is estimated that light pollution continues to grow at a rate of 6% per year. Roadway and parking lot lighting are the major culprits of light pollution and sky glow. Traditionally, an increase in brightness has been associated with safety. Surprisingly, statistics have revealed there’s no correlation between crime and lighted areas. In 2008, PG&E Corp., the San Francisco-based energy company, conducted a study of crime and lighting and found “either that there is no link between lighting and crime, or that any link is too subtle or complex to have been evident in the data.”

“There have been some communities that have looked very carefully as to what was really appropriate for their lighting levels,” says Kardel. “In the case of parking lots, it really is necessary to look at how much light is actually needed. More light isn’t always better. If you’ve got enough, adding more doesn’t make it any safer.”

According to the Illinois Coalition for Responsible Outdoor Lighting, the wisest of these towns and cities are starting from scratch, and defining under what circumstances they should be illuminating the night, to what levels, and during what hours. “Such analysis can bring the whole municipal ‘team’ onboard — besides the engineers and accountants, police, fire, and other community safety officers, as well as environmental groups, can work together on defining standards for streetlight installations. The municipalities then use those standards to analyze their existing lighting installations and alter the operation of or even remove streetlights that do not meet their own standards of necessity,” said the coalition.

The organization applauds an in-depth analysis of street-lighting practice, particularly when burdened with an aging, piecemeal system. “Every well-managed municipality should have standards to define when and where supplemental illumination is needed for safety, security, and/or convenience,” the organization writes on its website. “Most municipalities also operate street lighting that was installed over various eras by managers or developers who may well not have had modern considerations of energy efficiency or environmental and fiscal responsibility in mind. New, economical technologies are also available to control the operation of streetlights, allowing some to be turned off or dimmed during the hours when few citizens are out in certain areas; a light which is on only half of the night consumes 50% less energy than one left on all night (and has half the utility bill). Beyond energy efficiency, this analysis and standard setting should incorporate environmental, health, and safety concerns.”

To help communities interested in reducing light pollution while maintaining safety, IDA, in conjunction with the Illuminating Engineering Society of North America (IES), has published the Model Lighting Ordinance (MLO), available for download at http://www.ies.org/PDF/MLO/MLO_FINAL_June2011.pdf. Developed jointly by the IDA and the IES over a period of seven years, the MLO will give states and municipalities the ability to enact effective outdoor lighting legislation and codes, while maintaining the necessary lighting quality for a safe and secure lighted environment and meeting all relevant IES standards and practices, which can be met using readily available, reasonably priced lighting equipment.

Among the MLO’s features is the use of lighting zones, which allow each governing body to vary the stringency of lighting restrictions according to the sensitivity of the area as well as accommodating community intent. In this way, communities can fine-tune the impact of the MLO without having to customize the MLO. The ordinance also incorporates the backlight-uplight glare (BUG) rating system for outdoor-use luminaires, which provides more effective control of unwanted light. The MLO will be revised on a regular basis to include new information, feedback from municipalities using it, and changes to IES standards.

Seal of approval

“One of the odd things about outdoor lighting is that many times the decision about what to do is based on how it looks in the daytime, as opposed to how the luminaire performs,” says Kardel, who goes on to say that this is particularly true when municipalities choose a style of lighting that mimics period fixtures, such as gas lanterns. “Not all but some of those are terribly bad sources of glare and sky glow, and others are much more efficient, in terms of where the light goes,” Kardel says. “When decisions are based on how something looks, it doesn’t always give you the best results.”

To help end-users choose fixtures and luminaires, IDA has developed its Fixture Seal of Approval (FSA) program. The FSA provides objective, third-party certification for luminaires that minimize glare, reduce light trespass, and don’t pollute the night sky. For a modest fee, IDA evaluates the photometric data of any luminaire submitted by its manufacturer. When the fixture is approved, the manufacturer receives a seal of approval, which it can use to promote and advertise products.

“The organization realized that working with lighting manufacturers is actually quite important,” says Kardel. “If you want people to make changes in their practices, one way is to stand outside and shout and be angry, and another is to discuss things. By working directly with the manufacturers, we’ve come up with a way to actually give recognition to those manufacturers that are actually making dark-sky-friendly lighting.”

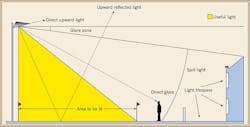

However, even approved luminaires can still cause light pollution if not applied correctly. This can be avoided by selecting luminaires that have the appropriate distribution for the application and installing them correctly to limit spill light and uplight (Figure). Additionally, the use of lighting controls can increase light pollution reduction. “Of course, this is an area that is going through big transformation now as changes in technology are coming,” says Kardel. “Some of that really has the potential to improve the situation quite a bit.”

IMS Research is forecasting that the uptake of smart lighting systems will increase considerably over the next five years, with more than 13.6 million smart street lighting components being shipped between 2010 to 2017. According to the firm’s recently published report, “The World Market for Connected Lighting Controls – 2012 Ed.,” the number of smart street lighting devices shipped will increase over the next five years to more than 3.4 million in 2017. Retrofit connectivity modules are projected to account for the majority of these shipments with most street smart lighting installations taking advantage of existing street lights.

Smart city

According to the IMS Research report, one of the main drivers for the uptake of smart street lighting systems is to reduce energy. While this can be done by replacing existing street lighting sources with LED street lights, which can dramatically reduce energy consumption, adding lighting controls is a lower cost solution. Another important benefit of installing lighting controls is the ability to reduce maintenance costs. Traditionally, faults are reported by the public, or by routine maintenance vans; however with street lighting control systems, faults can be detected centrally, reducing the need for routine maintenance checks.

Another key driver revealed in the report is the creation of an expandable infrastructure. By installing an intelligent lighting control system, cities can scale it up to manage other systems and improve their energy use and performance. Other systems that can also be integrated include traffic signals, energy meters, pollution sensors, parking-lot lights, and traffic sensors. These can all be integrated using the street-lighting control system as the backbone to provide connectivity. This can further reduce energy consumption as well as improve the performance of other systems and functions in a municipal region, effectively creating a “smart city.”

From 2009 to 2012, Santa Rosa, Calif., implemented a program to turn off or reduce the amount of time the city’s street lights were lighted, effectively cutting the city’s annual street lighting bill of $800,000 in half. Under the program, the city pulled the fuses on 6,000 of its 15,000 streetlights. An additional 3,000 streetlights were placed on a programmable photocell timer that shuts lights off from midnight to 5:30 a.m.

“The economy softened drastically, and we had to cut our general fund budget by 25% in an 18-month period,” says Rick Moshier, public works director for the city. “That was a big number for us.”

Not wanting to cut yet another of the last of the city’s two street-patching crews, Moshier examined the city’s electric bill. “I could either fix potholes or keep paying $800,000 a year for electricity,” he says. “If I didn’t cut the energy bill, I was going to have to go down to one crew.”

On a survey of the streetlights in the city, Moshier realized that some neighborhoods functioned well with less lighting. “I noticed that some parts of our city have fewer streetlights than others,” he explains. “But we weren’t getting complaints about too few streetlights in those areas. When I walked and drove them, they seemed adequately lit. Crime wasn’t any higher there than in other comparable parts of the city.”

As a result, the department modeled the reduction program on those neighborhoods. That’s how they determined spacing. But despite this careful consideration, residents of the city weren’t exactly thrilled to have darker streets. “I wouldn’t say the community loves it,” says Moshier. “It’s more like they tolerate it. We still get complaints, but we’re working it out.”

The department has no plans to reduce lighting any further. “We’ve done as much as can be done,” says Moshier.

In fact, it is now reviewing the reduction plan’s first neighborhood. “We’re finding that we need to come back and revisit it,” he continues. “We learned as we went along, and by the second year we had it fairly well figured out. So we don’t get as many complaints from the neighborhoods that we did in the second through fourth years. We’re having to circle back to the first neighborhood and make adjustments.”

The replacements

As a result of the reduction and replacement programs, an estimated 1,000 tons of greenhouse gas emissions from the city will be reduced annually. Additionally, ambient light levels will be reduced, allowing for greater visibility of the night sky. But the city’s main concern is still its bottom line.

The $400,000 in savings from the reductions consists of just the city’s electric utility bill. “We were counting only the things we knew we could cut,” says Moshier.

Most of the city’s streetlights aren’t metered. Santa Rosa pays its electric utility on a per-pole basis, depending on the wattage of the bulb. A 250W high-pressure sodium (HPS) bulb costs the city $146 a year to operate, whereas a 150W induction bulb costs $74 annually.

Therefore, the city also replaced some of its less efficient HPS lamps with new HPS, LED, and induction lamps — donated by the manufacturers for a comparison demonstration — that cost less to operate and will last longer. They installed these at signaled intersections. “We used them at signal light intersections because they’re metered and higher wattage, so the payoff is a little faster,” says Moshier. “The payoff is not as compelling for the lights with lower wattage.”

Based on results from its completed actions, the city now has to decide the fate of the thousands of other lower-wattage streetlamps. One argument is to replace them all as soon as possible. Moshier would like to use more LED technology. LED fixtures use around 50% of the energy, and they last around 15 years, whereas HPS lamps have a lifespan of around four years.

Now that LED lighting has become cost competitive with induction lighting, the city is pursuing a grant — $250,000 with an additional $50,000 rebate — from its electric utility to install that technology at arterial and collector streets.

“The price has come down enough where they’re neck and neck with induction,” says Moshier. “We’d like to do a fifth of the town per year and get the whole city done in five years. Then it would be very low labor after that. We wouldn’t have to go looking for burned out lights. We’d just replace them all proactively. But we’re looking for a way to afford it.”

Until the grant comes through, the city isn’t in a hurry. Currently, if a fixture needs to be taken down to be refurbished, it’s replaced with an LED instead of a new HPS lamp. If just the lamp needs to be changed, then it uses the newer HPS lamps. “We’re doing it ‘opportunistically,’” says Moshier. “We’re not saying we’re never going to do it, but we’re not feeling like we need to rush out and do it right away either. We’re taking it slow.”

SIDEBAR: Light Pollution Glossary

Sky glow is a brightening of the sky caused by both natural and human-made factors.

Light trespass is light being cast where it is not wanted or needed, such as light from a streetlight or a floodlight that illuminates a neighbor’s bedroom at night making it difficult to sleep.

Glare can be thought of as objectionable brightness. It can be disabling or discomforting. There are several kinds of glare, the worst of which is disability glare, because it causes a loss of visibility from stray light being scattered within the eye. Discomfort glare is the sensation of annoyance or even pain induced by overly bright sources. Think of driving along a dark road when an oncoming car with bright headlights suddenly appears. The sudden bright light can be uncomfortable and make it difficult to see. Discomfort and even disability glare can also be caused by streetlights, parking lot lights, floodlights, signs, sports field lighting, and decorative/landscape lights.

Sky glow occurs from both natural and human-made sources. Electric lighting is the human-made source of sky glow. Light that is either emitted directly upward by luminaires or reflected from the ground is scattered by dust and gas molecules in the atmosphere, producing a luminous background. Sky glow is highly variable, depending on immediate weather conditions, the quantity of dust and gas in the atmosphere, the amount of light directed skyward, and the direction from which it is viewed. In poor weather conditions, more particles are present in the atmosphere to scatter the upward-bound light, so sky glow becomes a very visible effect of wasted light and wasted energy.

Source: Lighting Research Center