Proper grounding and bonding prevent unwanted voltage on non-current-carrying metal objects, such as tool and appliance casings, raceways, and enclosures, as well as facilitate the correct operation of overcurrent devices. But beware of wiring everything to a ground rod and considering the job well done. There are certain subtleties you must follow to adhere to applicable NEC rules and provide safe installations to the public and working personnel. Although ground theory is a vast subject, on which whole volumes have been written, let's take a look at some of the most common grounding errors you may run into on a daily basis.

1. Improper replacement of non-grounding receptacles. Dwellings and non-dwellings often contain non-grounding receptacles (Photo 1). It's not the NEC's intent to immediately replace all noncompliant equipment with each new edition of the Code. In fact, it's perfectly fine to leave the old “two prongers” in place. But because an intact functioning equipment ground is such an obvious safety feature, most electricians tend to replace these old relics whenever possible.

There are several ways you can complete this upgrade, many of which are erroneous and strictly against the Code. For example, never apply the following non-NEC-compliant solutions:

- Hook up a new grounding receptacle on the theory that this is a step in the right direction. This can lead future electricians and occupants to believe they are fully protected by a non-functioning ground receptacle.

- Connect the green grounding terminal of a grounded receptacle via a short jumper to the grounded neutral conductor. This practice is totally noncompliant and dangerous because when a load is connected, voltage will appear on both the neutral and ground wires. Therefore, any noncurrent-carrying appliance or tool case will become energized, causing shock to the user, who is typically partially or totally grounded.

- Run an individual ground conductor from the green grounding terminal of a grounded receptacle to the nearest water pipe or other grounded object. This “floating ground” presents various hazards. It is likely that this ground rod of convenience will have several ohms of ground resistance so that, in case of ground fault within a connected tool or appliance, the breaker will not trip — and exposed metal will remain energized.

- Run an individual ground conductor back to the entrance panel, and connect it to the neutral bar or grounding strip. This solution is somewhat better, but still noncompliant. Any grounding conductor must be within the circuit cable or raceway. One objection is that an individual conductor could be damaged or removed in the course of work taking place in the future.

What are the correct ways to handle this type of situation, when you find yourself working with non-grounded receptacles?

- The best approach is to run a new branch circuit back to the panel, verifying presence of a valid ground. Since this procedure usually involves fishing cable behind walls or, in some cases, removing and then replacing wall finish, it's not always feasible unless a total rewiring job is being performed.

- Another possibility is to replace the two-prong receptacle with a GFCI. Hook up the two wires, and leave the grounding terminal unattached. Included with the GFCI is a sticker that says, “No equipment ground.” This sticker must be in place so that future electricians and users are not misled. The thinking behind this strategy is that even though the tool or appliance case is not grounded, the GFCI will provide enhanced safety. It's important to note that a GFCI functions properly without the presence of a grounding conductor. The device compares current flowing through the hot and neutral conductors and trips if a difference of more than 5 milliamps is detected.

- Non-grounding receptacles are still manufactured. If replacement is necessary (and acquiring a ground is not feasible), installation of a new non-grounding receptacle is a way to go.

2. Installation of a satellite dish, telephone, CATV, or other low-voltage equipment without proper grounding. If you look at a number of satellite dish installations in your neighborhood, a certain percentage will inevitably not be grounded at all. Of those that are grounded, there is still a high probability many are not fully compliant. For example, the grounding electrode conductor could be too long, too small, have unlisted clamps at terminations, have excess bends, or be connected to a single ground rod but not be bonded to other system grounds.

For NEC purposes, a satellite dish is an antenna, and installation requirements are found in Chapter 8, Communications Systems. Article 810, Radio and Television Equipment, details the installation requirements. Part II deals with receiving Equipment — Antenna Systems. This type of equipment, which includes the satellite dish, must have a listed antenna discharge unit, which can be either outside the building or inside between the point of entrance of the lead-in conductors and the receiver — and as near as possible to the entrance of the conductors to the building. The antenna discharge unit is not to be located near combustible material and certainly not within a hazardous (classified) location.

The antenna discharge unit must be grounded. The grounding conductor is usually copper; however, you can use aluminum or copper-clad aluminum if it's not in contact with masonry or earth. Outside, aluminum or copper-clad aluminum cannot be within 18 inches of the earth.

The grounding conductor can be bare or insulated, stranded or solid, and must be securely fastened in place and run in a straight line from the discharge unit to the grounding electrode (Photo 2). If the building has an intersystem bonding termination, the grounding conductor is to be connected to it or to one of the following:

- Grounding electrode system.

- Grounded interior metal water piping system within 5 feet of point of entrance to the building.

- Power service accessible grounding means external to the building.

- Metallic power service raceway.

- Service equipment enclosure.

- Grounding electrode conductor or its metal enclosure.

If this grounding conductor is installed within a metal raceway, you must bond the metal raceway to it at both ends. For this reason, if raceway is deemed necessary for extra protection, UL-listed PVC (rigid non-metallic conduit) is generally used. The grounding conductor must be no smaller than 10 AWG copper.

Where separate electrodes are used, you must connect the antenna discharge unit grounding means to the premises power system grounding system by a 6 AWG copper conductor. Needless to say, grounding a satellite dish goes well beyond simply driving a ground rod at the point of entrance.

Grounding for CATV is slightly different. Typically, CATV is brought into the building via coaxial cable, which has a center conductor, insulating spacer, and outer electrical shield. Because of the spacer, capacitive coupling is diminished so that the cable provides a high-quality signal for data, voice, and video transmission. Improper grounding of coaxial cable used for CATV is very common.

There is no antenna discharge unit as required for satellite dish installation. Instead, the shield of the coaxial cable is connected to an insulated grounding conductor that is limited to copper but may be stranded or solid. The grounding conductor is 14 AWG minimum so that it has current-carrying capacity approximately equal to the outer shield of the coaxial cable.

The major distinguishing characteristic is that for one- and two-family homes the grounding conductor cannot exceed 20 feet in length and should preferably be shorter. If a grounding electrode, such as the Intersystem Bonding Termination, is not within 20 feet, it is necessary to drive a ground rod for that purpose. However, even after this dedicated grounding means is established, in order to be NEC-compliant, the installation must have a bonding jumper not smaller than 6 AWG or equivalent, which is connected between the CATV system's grounding electrode and the power grounding electrode system for the building. Omitting this jumper is a serious Code violation, second only to no grounding at all. You must bond all system grounds, antenna, power, CATV, telephone, and so on with a heavy bonding jumper.

3. Non-installation of GFCIs where required. Recent Code editions have mandated increased use of GFCIs. In dwelling units, GFCIs are required on all 125V, single-phase, 15A and 20A receptacles in: bathrooms; garages; accessory buildings with a floor at or below grade level not intended as a habitable room, limited to storage, work and similar areas; outdoors; kitchens along countertops; within 6 feet of outside edge of laundry, utility, and wet bar sinks; and boathouses. In other than dwelling units, GFCIs are required on all 125V, single-phase, 15A and 20A receptacles in bathrooms, kitchens, rooftops, outdoors, and within 6 feet of the outside edge of sinks.

Other areas requiring the use of GFCIs include: boat hoists, aircraft hangars, drinking fountains, cord- and plug-connected vending machines, high-pressure spray washers, hydromassage bathtubs, carnivals, circuses, fairs (and the like), electrically operated pool covers, portable or mobile electric signs, electrified truck parking space supply equipment, elevators, dumbwaiters, escalators, moving walks, platform lifts/stairway chairlifts, fixed electric space heating cables, fountains, commercial garages, electrical equipment for naturally and artificially made bodies of water, pipeline heating, therapeutic pools and tubs, boathouses, construction sites, health care facilities, marinas/boatyards, pools, recreational vehicles, sensitive electronic equipment, spas, and hot tubs.

4. Improperly connecting the equipment-grounding conductor to the system neutral. You must connect a grounded neutral conductor to normally noncurrent-carrying metal parts of equipment, raceways, and enclosures only through the main bonding jumper (or, in the case of a separately derived system, through a system bonding jumper). Make this connection at the service disconnecting means, not downstream. When you buy a new entrance panel, a screw or other main bonding jumper is usually included in the packaging. Attached to it are instructions stipulating that it is to be installed only when the panel is to be used as service equipment.

It's a major error to install a main bonding jumper in a box used as a subpanel fed by a 4-wire feeder. It's also wrong not to install it when the panel is used as service equipment. Improper redundant connection of grounded neutral to equipment-grounding conductors can result in objectionable circulating current and presence of voltage on metal tool or appliance casings. You should connect grounded neutral and equipment-grounding conductors at the service disconnect. Then separate them — never to rejoin again. Additional optional ground rods may be connected anywhere along the equipment-grounding conductor but never to the grounded neutral.

5. Improperly grounding frames of electric ranges and clothes dryers. Prior to the 1996 version of the NEC, it was common practice to use the neutral as an equipment ground. Now, however, all frames of electric ranges, wall-mounted ovens, counter-mounted cooking units, clothes dryers, and outlet or junction boxes that are part of these circuits must be grounded by a fourth wire: the equipment-grounding conductor.

An exception permits retention of the pre-1996 arrangement for existing branch-circuit installations only where an equipment-grounding conductor is not present. Several other conditions must be met. If possible, the best course of action is to run a new 4-wire branch circuit from the panel. If you must keep an old appliance, be sure to remove the neutral to frame bonding jumper if an equipment-grounding conductor is to be connected.

6. Failure to ground submersible well pumps. At one time, submersible well pumps were not required to be grounded because they were not considered accessible. However, it was noted that workers would pull the pump, lay it on the ground, and energize it to see if it would spin. If, due to a wiring fault, the case became live, the overcurrent device would not function, causing a shock hazard. The 2008 NEC requires a fourth equipment-grounding conductor that you must now lug to the top of the well casing. Many people assume that in a 3-wire submersible pump system one wire is a “ground.” In actuality, submersible pump cable consists of three wires (plus equipment-grounding conductor) twisted together and unjacketed. Yellow is a common 240V leg, black is run, and red is start, which the control box energizes for a short period of time. Prior to the new grounding requirement, everything was hot.

7. Failure to properly attach the ground wire to electrical devices. Wiring daisy-chained devices in such a way that removing one of them breaks the equipment grounding continuity is a common problem. The preferred way to ground a wiring device is to connect incoming and outgoing equipment-grounding conductors to a short bare or green jumper. The bare or green insulated jumper is then connected to the grounding terminal of the device.

8. Failure to install a second ground rod where required. A single ground rod that does not have a resistance to ground of 25 ohms or less must be augmented by a second ground rod. Once the second ground rod is installed, it's not necessary for the two to meet the resistance requirement. As a practical matter, few electricians do the resistance measurement.

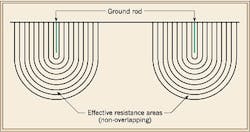

Figure. Non-overlapping effective resistance areas reduce net resistance.

You cannot use a simple ohmmeter because that would require a known perfect ground. Special equipment and procedures are needed, so it's common practice to simply drive a second ground rod. You must locate them at least 6 feet apart. Greater distance is even better (Figure). If both rods and the bare ground electrode conductor connecting them are directly under the drip line of the roof, ground resistance will be further diminished. This is because the soil along this line is more moist. Ground resistance greatly increases when soil becomes dry.

9. Failure to properly reattach metal raceway that is used as an equipment-grounding conductor. When equipment is relocated, replaced, or removed for repair, many times equipment ground paths are broken. If these connections are not fixed, there's an accident waiting to happen (Photo 3). Setscrews, locknuts, and threads should be fully engaged and continuity tests performed before equipment is put back into service. Dirt and corrosion can also compromise ground continuity.

NEC Article 250.4 requires that electrical equipment, wiring, and other electrically conductive material likely to become energized shall be installed in a manner that creates a low-impedance circuit from any point on the wiring system to the electrical supply source to facilitate the operation of overcurrent devices.

10. Failure to bond equipment ground to water pipe. Improper connections are often seen in the field. Screw clamps and other improvised connections do not provide permanent low impedance bonding. The worst method would be to just wrap the wire around the pipe or to omit this bonding altogether.

In a dwelling, a conductor must be run to metallic water pipe, if present, and connected with a UL-listed pipe grounding clamp (Photo 4). This bonding conductor is to be sized according to Table 250.66, based on the size of the largest ungrounded service entrance conductor or equivalent area for parallel conductors.

Herres is a licensed master electrician in Stewartstown, N.H. He can be reached at [email protected].

About the Author

David Herres

Licensed Master Electrician

David Herres is a licensed master electrician in Stewartstown, N.H. He can be reached at [email protected].